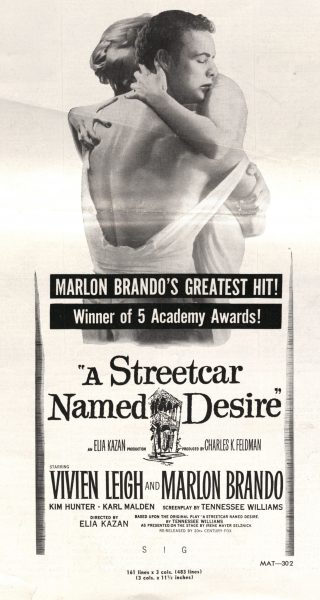

Image from the press book for “A Streetcar Named Desire”. Image courtesy of Twentieth Century Fox

A Streetcar Named Desire is the title of a 1947 Pulitzer Prize-winning play by Tennessee Williams, adapted in 1951 for the big screen by director Elia Kazan. It is undoubtedly one of the most famous film depictions of the City of New Orleans, despite the fact that the much of the production took place in Burbank, CA film studios. The creation of Streetcar and its ongoing impact on the image of New Orleans is particularly interesting in our modern era of “runaway production,” in which many states offer tax incentives to lure production to locations outside of Hollywood. In the early 1950s however, film crews were much less mobile and the industry was highly concentrated in Southern California. (Twentieth Century Fox, Press Book for “A Streetcar Named Desire.”)

Regardless of the filming location, even today, the sultry depiction of New Orleans’ French Quarter provides a draw to tourists interested in seeing where Stanley (played by Marlon Brando) famously bellowed “Hey Stella!” to his wife from the base of the curving wrought iron stairs of their rundown apartment.

Plot Summary

Streetcar begins with Blanche (Vivien Leigh) arriving at her sister Stella’s (Kim Hunter) run-down apartment in the French Quarter. Blanche lives in a “dream world of long-gone gentility,” and is dismayed by her sister’s way of life, including her marriage to brutish Stanley (Marlon Brando). Throughout the script, Stanley taunts Blanche, eventually revealing a secret that sends her into a complete breakdown. Ultimately Stanley is rebuffed by his wife and friends, left alone to witness the result of his cruelty. (“Orleans in Another Film.” Times Picayune , October 28, 1951, Section 2, 10.)

The famous opening scene of the film shows Blanche arriving at Stella’s French Quarter apartment aboard a trolley car displaying the name “Desire,” on the front. This is referential to the Desire Streetcar line, which ceased operation before the film was released. One of the “Desire” cars was recalled from retirement by then Mayor Morrison and New Orleans Public Service for the shooting of the opening scene at the L&N station at the foot of Canal street. (“Orleans in Another Film.” Times Picayune , October 28, 1951, Section 2, 10.)

Richard Day, who won an Academy Award for the sets he created for the film, “had to create a scene that was both real and believable, yet symbolic of decay and gradual disintegration.” Further, “they had to be the kind of scenes you might see in certain parts of New Orleans.” Day travelled to New Orleans for several weeks before production began to find inspiration in “picturesque aspects of various street and buildings of the Vieux Carre,” resulting in a “striking set for the “Elysian Fields apartments” in which the majority of the film’s action is set. (Twentieth Century Fox, Press Book for “A Streetcar Named Desire.”)

Impact of the Film on New Orleans Image and Tourism

Whether the scenes of A Streetcar Named Desire were filmed on location in New Orleans or recreated on a Hollywood Sound Stage, the image of the city was spread throughout the states. A press booklet promoting the theatrical re-release of the film after the 24th Academy Awards (where the film received five awards) suggests,

“A Streetcar Named Desire reveals a side to the lovely Southern city that has startled American play and motion picture fans.”

The booklet provides suggestions for theater’s marketing a public relations strategies revolving around the imagery of the Streetcar. For example, the booklet suggests that promoters “contact your local transit company about the possibility of arranging a special discount to those who take a streetcar or bus to see the film at your theater.” In more suburban areas, the booklet suggests a “Desire limited” theme, in which one selected bus is designated to make a special one-time trip to a densely populated residential area, taking viewers directly to the theater to watch the film. (M’Lean, James. “Carroll Lists Imaginative Steps Boosting Tourism.” Times Picayune, August 19, 1965, Section 2, 30.)

In 1965, fourteen years after the release of the film, state tourist director John Carroll attempted to revive the imagery of the Desire Streetcar to spur tourism interest. Originally from New Orleans but trained in Hollywood, Carroll emphasized that the state needed to “think big if it wanted to get into the big league in tourism.” One of his suggestions included putting the “streetcar named Desire” on a trailer and send it “rolling around the country loaded with promotional materials for potential visitors.” Additionally, an undated, but probably 60s-era tourism brochure features a map of the Desire streetcar line’s former route. (M’Lean, James. “Carroll Lists Imaginative Steps Boosting Tourism.” Times Picayune, August 19, 1965, Section 2, 30.)

Today, visitors to New Orleans have a few options for “Streetcar” tourism. A touring company called “The Original New Orleans Movie Tours” has made a profitable business off the New Orleans film locations and includes scenes from a Streetcar Named Desire. Visitors can also visit Stella! or Stanley, two acclaimed restaurants in the French Quarter by chef Scott Boswell, each named after the characters from the story.* Christopherson, Susan. “Divide and Conquer: Regional Competition in a Concentrated Media Industry.” In Contracting Out Hollywood edited by Greg Elmer and Mike Gusher. Oxford: Roman and Littlefield, 2005.

I had no idea