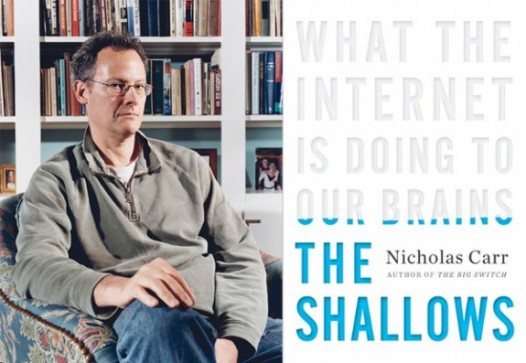

Loyola University New Orleans will host Nicholas Carr, author of The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, April 17, in Roussel Hall (corner of St. Charles Ave. and Calhoun St.) on the university’s main campus.

Loyola University New Orleans will host Nicholas Carr, author of The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, April 17, in Roussel Hall (corner of St. Charles Ave. and Calhoun St.) on the university’s main campus.

The Shallows chronicles the history of intellectual technologies, beginning with maps and continuing into the Internet age, and draws from neurological and psychological research to argue that, while the Internet provides for us incredible possibilities, the way in which we interact with it is transforming our minds, obliterating our ability for deep, contemplative thought.

The event is part of Loyola’s Presidential Centennial Guest Speaker Series, which, throughout the past few months, has presented the archbishop of New Orleans, Wynton Marsalis, Cokie Roberts, and a handful of Catholic scholars. Carr seems at first a bit of an odd choice in this lineup, but because of issues facing U.S. higher education and the preoccupations of Loyola’s president, his selection makes perfect sense.

Kevin Wildes, a Jesuit priest and president of Loyola, has spoken plainly about his concerns regarding the wholesale adoption of online technologies in education. In remarksto the faculty and staff of Loyola last summer, he noted that American culture has a bias toward technology and “the new,” and that we tend to assume that the latest and newest technology is the “best.” In his talk, Wildes conceded that St. Ignatius of Loyola—who founded the Jesuit order 400 years ago and set forth the pedagogical framework that Jesuit schools around the world follow to this day—fervently adopted the latest technology of his time (pens, ink, paper) and that the Jesuit way of proceeding encourages priests to “meet people where they are” (in this case, online all the time). But he went on to express his reservations toward online education that illuminate his selection of Carr as a speaker:

We are not only concerned with the accumulation of courses and information but with the education of the whole person. In our model of a university teaching a course is not simply handing out information. Education, in a Jesuit university, takes place in community and in discussion. As someone who has taught online courses, I am continually struck by the challenge of creating intellectual community. Real time discussion allows students to learn from the professor and one another.

As someone who teaches regularly I know the value to the evolving communications technologies tied to the Internet. They can support, aid, and assist what we do with students and they can open doors for us, particularly with graduate and professional students. But, in a Jesuit model of education I think the formative part of the education we promise, which goes beyond the mere assembling of information, needs to take place face to face.

It might be easy to think of Wildes, a priest-scholar and philosopher, as a sure fit in the category of people who would tend to be suspicious of the Internet (even though his expertise is in bioethics, a field deeply entwined with technology). Another who comes to mind is Lewis Lapham—the long-time Harper’s editor, silverhair, and print devotee—whose current project, Lapham’s Quarterly, collects great thought from throughout the ages in handsome themed issues. In a piece about Lapham in Smithsonian Magazine, Ron Rosenbaum described the paradox Lapham confronts:

Suddenly thanks to Google Books, JSTOR and the like, all the great thinkers of all the civilizations past and present are one or two clicks away. The great library of Alexandria, nexus of all the learning of the ancient world that burned to the ground, has risen from the ashes online. And yet—here is the paradox—the wisdom of the ages is in some ways more distant and difficult to find than ever, buried like lost treasure beneath a fathomless ocean of online ignorance and trivia that makes what is worthy and timeless more inaccessible than ever.

Nicholas Carr, on the other hand, is a less likely Internet skeptic. He is a technology writer whose previous books parse complex questions related to IT management and liken the trend toward universal Internet connection to the emergence of the electricity grid. He was on the steering board of the World Economic Forum’s cloud computing project, frequently contributes to Wired, and his work has appeared in the Best Technology Writing anthology (among many other places).

Carr has said his inspiration to write The Shallows came from his own experience feeling his mind morph as a result of being online. He would be reading a book—an activity that had always come to him naturally—but before long his attention would drift and he would feel compelled to put the book down, check his email, Google something. After dispelling the notion that he was merely succumbing to middle-age brain rot, he began looking into the ways in which his interaction with the Internet was making him unable to concentrate.

Perhaps the finest recent account through a personal lens of the way in which the Internet affects us is “Generation Why?” Zadie Smith’s ostensible review of David Fincher’s The Social Network and Jaron Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget. In Smith’s trademark style, the essay cleaves closely to her thoughts and emotions while making its points and even recounts the author’s decision to delete her Facebook account. She ends the piece by concluding The Social Network is not a film damning “any particular real-world person called ‘Mark Zuckerberg.’ It’s a cruel portrait of us: 500 million sentient people entrapped in the recent careless thoughts of a Harvard sophomore.”

Because Nicholas Carr’s talk about The Shallows will take place on a university campus, the majority of those in attendance will be students. There could not be a more appropriate audience, though it’s unclear how they will receive Carr’s warnings. In Smith’s essay, she pontificates whether a gulf has emerged between people divided by the ways in which they engage the Internet. She imagines herself on one side while an increasingly large group of young people gathers (or is already on) the other:

How long is a generation these days? I must be in Mark Zuckerberg’s generation—there are only nine years between us—but somehow it doesn’t feel that way. This despite the fact that I can say (like everyone else on Harvard’s campus in the fall of 2003) that “I was there” at Facebook’s inception … At the time, though, I felt distant from Zuckerberg and all the kids at Harvard. I still feel distant from them now, ever more so, as I increasingly opt out (by choice, by default) of the things they have embraced. We have different ideas about things. Specifically we have different ideas about what a person is, or should be. I often worry that my idea of personhood is nostalgic, irrational, inaccurate. Perhaps Generation Facebook have built their virtual mansions in good faith, in order to house the People 2.0 they genuinely are, and if I feel uncomfortable within them it is because I am stuck at Person 1.0. Then again, the more time I spend with the tail end of Generation Facebook (in the shape of my students) the more convinced I become that some of the software currently shaping their generation is unworthy of them. They are more interesting than it is. They deserve better.

Reposted from Press Street: Room 220.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.