Jazz Fest food: Something old, something new

“I had a bread pudding at French Quarter Fest that was so good I had to stop and call my mama,” said one of our group of food tasters Friday at the 2013 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

And that’s just what we were looking for in our daylong grazing at the Fair Grounds: call-your-mama-good dishes.

I was a young and inexperienced food editor at The Times-Picayune in the early ‘80s when the paper first gave a team of hungry reporters and photographers a unique but appetizing assignment: Taste every dish at Jazz Fest and report back.

We’ve done it every year since. And even though I left the paper in 2009, I have been generously granted emeritus status with the annual TP Jazz Fest tasting group. This year the report went online, with several Nola.com bloggers chronicling the tasting results in real time; a print version of the culinary reports also will appear in Friday’s Lagniappe.

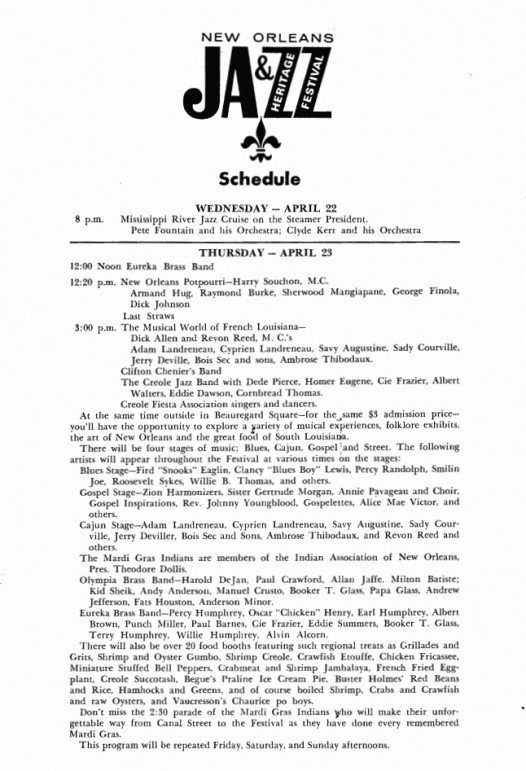

Much has changed over the three decades I’ve been chronicling Jazz Fest foods. The $3 admission price at the first fest is ancient history, the original four stages of music have blossomed to 12, and the 20 initial food booths have increased almost fourfold. Not to mention the upsurge in crowds, tattoos, totems, crafts and parking headaches.

The first time the TP tasting team hit the Fair Grounds, I recall asking (with trepidation) for a $200 advance to cover the cost of all the dishes at the fest. I don’t know what the price tag runs now, but with more than 70 food purveyors and a top price of $12 for a combo plate, it will no doubt soon climb to four figures.

The 1970 Jazz Fest program: iconic dishes from the start.

Time was when we didn’t venture into the field without blankets to spread on the grass, napkins for wiping greasy fingers, pads and pens for our tasting notes. Now the event provides shaded tables and chairs and hand-washing stations, and the reporting has gone digital.

In the early days, we would give our tasting leftovers to festival-goers, who eagerly accepted half-eaten dishes of alligator sausage or andouille gumbo for sampling. Along about the mid-‘90s, wariness set in: Fellow festers began to look askance when we offered them the remaining half of a shrimp po-boy or a handful of boiled crawfish, and takers were rare. I was gladdened this year when a friendly couple from Mexico, seated at the far end of our table, happily dug into whatever we hadn’t eaten when tasting chores were done. Is the world becoming a less suspicious place?

Despite all the changes, the one Jazz Fest constant through the decades has been a significant one: its authenticity. Fair Grounds food has never been, well, fairgrounds food.

In fact, the 2013 tasting team would have been right at home with the 1970 Jazz Fest menu. It included:

Buster Holmes, whose red beans were the city’s iconic version of this traditional Monday dish, died in 1994, and Begue’s restaurant in the Royal Sonesta Hotel closed a couple of years ago. But Vaucresson’s sausage po-boys are still around, and Judy Burks, a 35-year Jazz Fest veteran, turns out a plate of red beans and rice smooth enough to make Buster’s former customers smile.

Friday’s standouts ranged from a savory Japanese barbecue po-poy (who knew?) to a greasy brown-paper bag filled with addictively fried cracklings; from the tried-and-true comfort of expertly fried chicken to the seductive allure of a cochon de lait po-boy.

Other personal favorites:

Like the city itself, the Jazz Fest menu at its best looks both back and ahead, offering a salute to what we’ve always done well, combined with an appreciation for innovation.

If only New Orleans’ politicians could emulate its best cooks.

Renee Peck is editor of NolaVie.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.