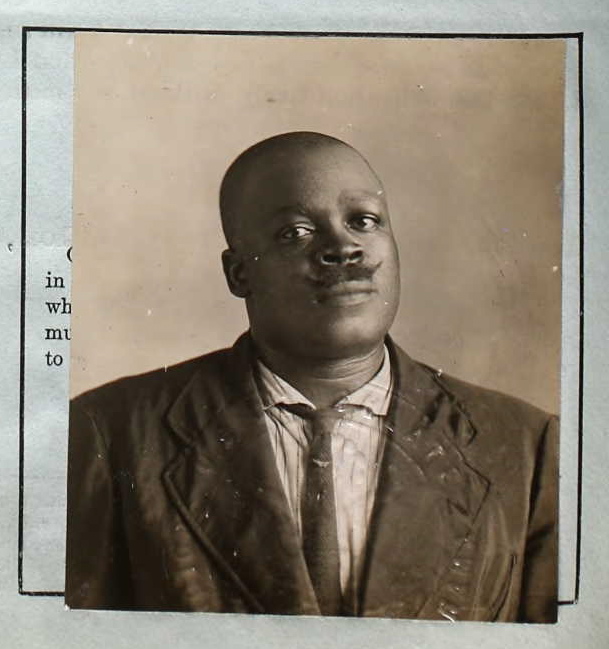

Jack Johnson, in a photo included for his passport application. Photo provided by Dave Miller.

New Orleans, ever a city of culture and diversity, was not always inhabited by those tolerant of the medley of people it supported. At the turn of the 20th century, when Jim Crow made the laws, and the Klu Klux Klan actively made the lives of African-American citizens difficult, one man found a way to defy the status quo. Blessed with the physical prowess to do so, John Arthur Johnson fought and took the dignity back that had been stolen by racial oppression. Considered a hero by blacks, but a devil by whites, Johnson’s historical significance had a nationwide effect, especially in a city like New Orleans. A city that had just weathered the racial tension surrounding Plessy vs. Ferguson, found itself again facing the conversation no white citizen wanted to have at the time. Could the races be equal? Through newspaper and print, the New Orleans citizen’s opinions were recorded in history; and so, the impact Johnson had on the culture of the city can be understood today.

John Arthur Johnson-commonly known as Jack Johnson- was born on March 31, 1878 to Henry and Tiny Johnson in Galveston, TX (“Jack Johnson Biography”) . He lived his life as a boxer and at times a boxing champion. Often called the Galveston Giant, Johnson dominated the heavyweight boxing world from 1908 to 1915. Considered a pot stirrer and likely to misbehave by white America, he was a black celebrity for the African-American community all over the United States (“Major Problems in the History of the American South Volume II: The New South”, 2012). Raised by his crippled father and young mother Johnson grew up in the streets and boat yards of Galveston, TX (“Papa Jack: Jack Johnson and the Era of White Hopes”, 1983). Johnson’s father, Henry Johnson, bought and built on their family’s tiny plot of land in the city of Galveston in 1881. Henry was born into slavery in Maryland and is rumored to have been a part of bare-knuckle slave fighting for the entertainment of white slave owners before emancipation and the Civil War. While no real record of Jack Johnson’s first fight exists, it is more than likely that he began in the “Battle Royals” that took place in Texas and other southern states around the time of Johnson’s youth. These Battle Royals were brutal tests of young black men’s fighting skills, normally by white men and organizers. Little above a fighting slave, boys and young men would enter into melee competition with each other or into one on one fights while tied together by the ankle or wrist. Fighting only for pennies and nickels, Battle Royals furthered ideas surrounding the caste placement of African-Americans in the late and early 19th and 20th centuries. Always as fighting as the servant for the ,but never as, the master (“Papa Jack: Jack Johnson and the Era of White Hopes”, 1983).

Johnson’s first registered fight occurred in 1897 on November 1st as he fought for the Texas State Middleweight Title against Charley Brooks. Six short years later on February 5th, 1903 Johnson won the Colored Heavy Weight Title by beating Denver Ed Martin by points in Los Angeles, CA. At that time, due to Jim Crow race relations, white champions wouldn’t step into the ring with black boxers. Separate titles were given by race for this reason. Finally, on December 26, 1908 Johnson got his chance at the Heavyweight World Title against Tommy Burns. Johnson won that day in Sydney, Australia and became the first black heavyweight champion of the world. Johnson held on to the title until Jess Willard took it away from him in Havana, Cuba on April 5th, 1915. After six years of holding on to the championship Johnson continued to box until 1931 for 16 more years. When he ended his career he had a total of 704 rounds boxed and 77 matches, 54 wins, 11 losses, and 9 draws (“Jack Johnson.”).

Jack Johnson’s success in the ring against white opponents like Tommy Burns, and later against Jim Jeffries, as well as his open consorting with white women were both considered “deadly sins” at the time (“Major Problems in the History of the American South Volume II: The New South”, 2012) . So much was Johnson hated in the white community for his transgressions that even mentioning Johnson’s name in conversation with white southerners was enough to incite violence. White southerners, so aware of the blow done to the Jim Crow status quo by Johnson, wrote warnings in newspapers against black residents imagining that they were Jack Johnson because they would “get an awful beating. Due to Johnson’s successes as well as his rejection of the rules that said he was less than any other man, many a African-American citizen found themselves cornered and beat by white men seeking to take back the respect stolen from them by Johnson. Race riots were common at the time. So much so that newspapers like the Times-Picayune called them “usual” in their headlines (Usual Negro Riot Follows in Wake of Masked March on Claiborne Street.”, 1908). Also usual at the time was the taboo against African-American men associating with white women. The taboo was so strong that just the thought of it alone could cause riots as seen in many southern cities, including New Orleans. Johnson laughed in the face of that taboo and consorted with many white women over his lifetime. While records are incomplete it is thought that he married at least four of them. Despite his confidence Johnson ended up paying the price to the white elite. He was arrested on October 18, 1912 in Chicago (“Guide To The News City And Suburban.”, 1912). The case was based loosely around the thought that the woman with Johnson was involved with prostitution, but the larger cause behind the arrest was because of Johnson’s race. The charge, though, must have been uninteresting and common for an African-American male at the time; and so, it only sequestered one sentence in the Times-Picayune the day after the arrest. Johnson evaded his prison sentence for seven years in Europe, but returned in 1920 in order to serve his time for the false crime (“Jack Johnson Biography”, 2013).

As regularly racist as most news media was during the life and times of Jack Johnson, the Times-Picayune was relatively unbiased in describing Johnson’s successes over his white opponents (“Mack’s Melange Of Interesting Boxing Gossip.”, 1905) . In most cases only the words “negro” or “black” were used in describing Johnson as a fighter. In this way, it seems the Times-Picayune was a respectable non-biased newspaper for the New Orleans area. Though not too unbiased; the white read and written newspaper had picked an obvious favorite in the fights between Jack Johnson and Jim Jeffries. In one issue, a depiction of Uncle Sam in a boxing ring with gloves on symbolized how Jeffries would fight Johnson and take back the title for America (“No Title”, September 4, 1910) . This idea that Johnson was not a true American because of his black skin traces its roots all the way back to the Dred Scott case asserting that slaves were not true citizens of the United States. The assumption of second class citizenship or sub-citizenship of African-Americans in the United States would hold strong until after Johnson dies. Jeffries’ elitism is captured in text as well. Jeffries speaks of defending the athletic superiority of the white race when he steps into the ring with Johnson as reported by the Times-Picayune the day before the fight (“Last Word From Jeff And Jack On Eve Of Great Struggle” July 4, 1910). It became more and more clear in the days that lead up to the fight that every white American in the country was rooting for Jeffries to win, and despite his old age and come-back status, they did expect him to come out victorious. Unfortunately for their pride he did not. Jeffries went down in the fifteenth round and as his seconds called to stop the fight Johnson won by a technical knock out (“Jack Johnson.”). Along side their silence; animosity towards Johnson could be felt in the crowd, again as described by the Times-Picayune the day after the fight. Jeffries, labeled a fallen idol by the Times-Picayune, continued to exemplify the hopes and dreams of white supremacy even in his failure. Jeffries proves to be a respectable man in his actions, unlike the slander coming from his supporters in the media. Throughout the fight and after there are no quotes of racist slander from Jeffries in the Times-Picayune (“The Great Ring Battle At Reno Described By Rounds” July 5, 1910).

While Jack Johnson was the first, he was not the only African-American boxing champion to be in the spotlight of a racist public. Joe Louis was the second African-American to win the heavyweight title before World War II (Boxing’s Sambo Twins: Racial Stereotypes in Jack Johnson and Joe Louis Newpaper Cartoons, 1908 to 1938.”, 1988). Joe’s public relations legacy differs from Jack’s in every way, especially towards the end of Joe’s career. While Louis endured some of the same harsh reviews as black boxer that Johnson did, Louis didn’t push back like Johnson. In the beginning though, both boxers faced the same scrutiny because of the color of their skin. Sambo mask depictions plagued both fighters as each were shown drawn crudely in newspapers around the country. A sambo mask depiction was a cartoon variant of the racist ideal African-American man. The racist ideal is slow witted, has speech impediments, is subservient, and many times is drawn with an obsession with watermelon or chicken. Johnson, for his whole life is the enemy of the white race. Louis, though, was fighting at the right time to gain support of all audiences in the United States, regardless of color. Reason being that Louis, pitted against German Schmeling, became an American hero fighting for the pride of the United States. White America united against the Nazis for political reasons as black America did the same for social reasons. Both would support Louis in his fight against Schmeling and the sambo mask depictions of Louis would eventually cease in order to make room for more flattering humanistic portraits of the fighter (Boxing’s Sambo Twins: Racial Stereotypes in Jack Johnson and Joe Louis Newpaper Cartoons, 1908 to 1938.”, 1988).

Boxing was a central to life in New Orleans, even before Johnson began rocking the boat. Back when Kenner, LA was called “Kennerville” the first world championship heavyweight bout was fought in 1870. Still there today is a statue to commemorate the match, just outside New Orleans. Similar to Johnson’s case, on September 6, 1892 in a featherweight prize fight to determine the world champion was fought between George Dixon and Jack Skelly (“Quickly Finished by Dixon,” September 7, 1892). Dixon won, but the problem with that was Dixon was a black man. The editor of the Times-Democrat in New Orleans was credited at the time for saying that the match was “a mistake to bring the races together on any terms of equality” (“World Championship Fights in New Orleans”). Much like how Johnson was denied true satisfaction from his wins, Dixon in this case had his glory stolen by racist sentiment. A century ago, the city of New Orleans was in the center of the figurative boxing ring of public interest. In the center of that ring was the Coliseum. A boxing arena built in 1922; the Coliseum hosted a plethora of boxing greats like Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, and Max Baer. For 38 years the Coliseum hosted the boxing events that fed entertainment to a city on the corner of Roman and Conti (“When Did Jack Dempsey Come Here to Fight in a Boxing Match?” January 22, 2002). Formerly a boxing capital, New Orleans has a history rich with boxing tradition that continues today in community gyms scattered throughout the city such as Freret Street Boxing Gym, Uptown Boxing Fitness Center, and Crescent City Boxing Gym.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] Jack Johnson the Boxer […]