Stray Leaves, a monthly(ish) column of New Orleans literary obscurities by Michael Allen Zell, is a lifting up of stones and crowing about that found underneath, led by the guiding notion that we are standing on the shoulders of writers and books that deserve their names and faces returned to the public.

By Michael Allen Zell

By Michael Allen Zell

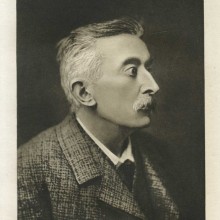

Eighty years ago, Raymond Chandler said somewhere that there are no vital and significant forms of art, only art, little of it at that, mostly nicely packaged substitutes. No question what Chandler would think of the prevalent counterfeit culture present-day in this country. Gladly turning back the opposite direction, though, a few decades before Chandler’s rumination, one of the exceptions, idiosyncratic author Lafcadio Hearn, inarguably produced art for the reading public at a time in which writers learned and slow-cooked their craft by reading and writing voraciously.

For the sake of this piece, I’d like to first emphasize two key points about Hearn: 1) Despite an open curiosity leading to heterogenous content full of beautiful imagery, he certainly could occasion into prose that one needn’t have synesthesia to call purple; 2) His own tastes ran far more underground and macabre (of the type “which no paper has published or dare publish,” although his inaugural news story in Cincinnati is stunningly gruesome) than what paying the bills necessitated in writing chiefly for the New Orleans Daily City Item and Harper’s Weekly newspaper.

Enter Letters From The Raven (Letters), long out of print, at least in editions of any care and quality. The eponymously titled main part begins with Hearn briefly in Memphis and newly arrived in New Orleans, down the river from Cincinnati. He quickly shunted his forename Patrick—and slangier Paddy, often used in the Midwest—to embrace his Greek heritage by fully using his middle name, Lafcadio, and in this he began the reinvention of himself like so many have done before and since. Letters is key in the Hearn collection because his language is keenly readable, his subject matter expedient, a lighter fun-loving side occasionally revealed, and the time in his life formative. He absorbed and emanated New Orleans, a city he wryly romanticized and by which he was no less disillusioned.

I’m not suggesting that Letters is the skeleton key or Babel-book to unlock Hearn or his work. In fact, Elizabeth Bisland’s two-volume The Life And Letters Of Lafcadio Hearn has far more content, so also far more elucidation. But, the written walks through a life found in Letters mainly covers the period when the Poe-obsessed grim young man was a fledgling on the verge of becoming Lafcadio Hearn, eventually an internationally known writer of far more commercial enterprise than his tastes would suggest. He had to invent Lafcadio Hearn before he could invent New Orleans, particularly to readers outside the city. If—like the subject of “An Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge,” a short story by his contemporary Ambrose Bierce (under much better circumstances)—Hearn had been able to flash forward in time at an instant to see how his decade-shy life in New Orleans, brief skip to the West Indies, and final period in Japan would end up, he might have felt calm and proud. Instead, the not-knowing that we all must bridge found him hungry, physically and figuratively.

And what does a hungry person with wits do? Start a restaurant. All dishes 5 cents. Let’s step back a bit, though. Letters, edited and with critical comment by Milton Bronner, chiefly consists of correspondence from Hearn to his Cincinnati benefactor Henry Watkin, an Englishman who ran a print shop and not only got Hearn his first newspaper job but initially provided him work, food, and lodging when the 19 year old arrived penniless to the United States. Nicknames were in order. Hearn called his elder Old Man or Dad. Watkin called his younger The Raven, which was so much to Hearn’s liking that for years he drew a raven now and again to serve as his signature in letters or notes to Watkin.

Hearn’s effusing of, “I never beheld anything so beautiful and so sad. When I saw it first—sunrise over Louisiana—the tears sprang to my eyes…One can do much here with very little capital,” upon arriving in mid-November 1877 turned cheerless by June 1878: “Have been here seven months and never made one cent in the city…Twenty dollars per month is a good living here; but it’s simply impossible to make even ten…Have been cheated and swindled considerably; and have cheated and swindled others in retaliation. We are about even.”

That same month he gained an assistant editor job with the Item. It paid little, though, so around a year later The 5 cent Restaurant opened at 160 Dryades Street (now a University Place parking garage between Canal and Common Streets), run by Hearn and his partner, “a large and ferocious man, who kills people that disagree with their coffee.” Doing business as “the cheapest eating-house in the South” with this sort proved to be the great undoing of his brief culinary experiment. As well, Hearn had not yet lived for a year in New Orleans before discontent and wanderlust settled in, so he actively learned Spanish to prepare for an expected uprooting to Cuba or Mexico, with Japan beginning to enter the mix.

Around the time of his Stray Leaves from Strange Literatures (this column is its abridged namesake), writing jobs began to pick up, particularly a well-paying one with Harper’s Weekly (he received $60 for his essential piece on St. Malo in 1883), to which he was referred by George Washington Cable. Correspondence with Watkin was silent for five years as Hearn became tremendously busy, particularly in the newspaper world and with French translations. Publisher interest and the West Indies followed. Letterstouches lightly on the years in Japan, ending with this in May of 1896, “I am a Japanese citizen now (Y. Koizumi),—adopted into the family of my wife…”

Letters also contains the shorter Letters to a Lady, consisting of his 1876 Cincinnati missives, and the more interesting Letters of Ozias Midwinter from 1877 – 1885. Let’s conclude with Hearn’s own thoughts upon arriving at “the gate of the tropics”: Eighteen miles of levee! London, with all the gloomy vastness of her docks and her ‘river of ten thousand masts,’ can offer no spectacle so picturesquely attractive and so varied in the attraction.

This article by Michael Allen Zell is reposted from Press Street: Room 220, a content partner of NolaVie.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.