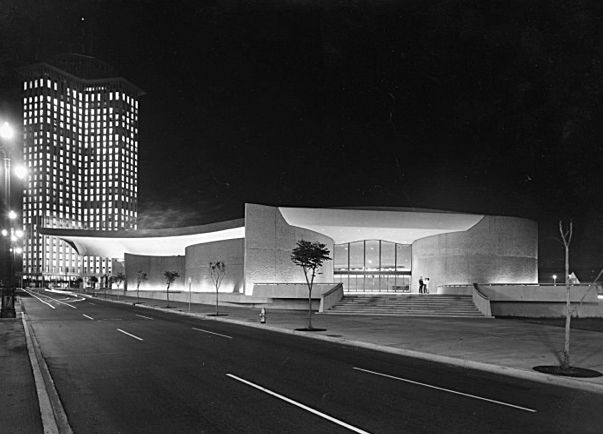

Architect’s rendering of the WTC and Rivergate ensemble (Photo by Skyscraperpage.com)

From childhood, my brother Don and I heard tales about Ole Man River from our mother, who grew up just blocks from the Mighty Mississip’. She and her siblings swam in the river, but they made their mark as the swimming Damontes at the expansive Audubon Park pool just down the block.

On October 27, 1929, Naomi and her brother Lowell won the men’s and women’s divisions of the cross-river swim from near Avondale to the foot of Canal Street, held to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of the setting of the Eads jetties in 1879 that would keep the mouth of the river from closing up with silt.

She told us of the swift currents and eddies that made swimming the last 50 yards to shore as difficult and time-consuming as the actual long-distance crossing of the river.

On that foggy October morning, the foot of Canal Street became a sacred spot for her; and years later, as she engaged in trade with Latin American countries, she thought of it as New Orleans’ true Gateway to the Americas.

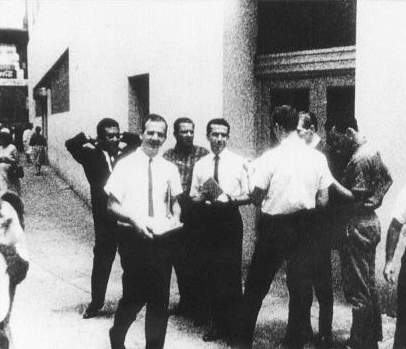

Lee Harvey Oswald distributing Fair Play for Cuba leaflets outside the original ITM, August 16, 1963. (Photo by WDSU-TV cameraman Johann Rush)

She took us to see the displays of exotic merchandise behind plate-glass windows in the original International Trade Mart, a 1946 five-story modernist building at the corner of Camp and Common, just five blocks from the river. Directed by Clay Shaw, the building was the ironic backdrop in the grainy black-and-white photos of Lee Harvey Oswald distributing Fair Play for Cuba leaflets in the early 1960s.

Foreign trade was thriving in New Orleans in those decades; and when the directors of International House and the International Trade Mart decided in 1957 that a larger and more impressive building — a towering “Temple of Trade” — was needed to proclaim the city’s pre-eminence in world trade, my mother took a special interest in the developing plans.

Especially the location of the new structure.

This was the time when Duncan Plaza was conceived as a shining center of government for the city, and civic leaders expressed interest in having the new International Trade Mart building as part of the developing complex, along with the new City Hall, State Office Building, Louisiana Supreme Court and New Orleans Public Library, all of contemporary design to showcase the city’s prosperity and dedication to the future.

But Naomi Marshall had other ideas. As the first woman to serve on the New Orleans Board of Trade and Export Managers Club, her opinion had clout, and she wrote a forceful letter to Captain Neville Landry, an engineering and manufacturing powerhouse, head of Equitable Equipment, director of International House and 1957 Times-Picayune Loving Cup recipient.

WTC tower under construction, showing undeveloped surroundings in the 1960s.

Following her dictum, “Act like a woman and think a man,” she told her story of infatuation with the river, but based her opinion on a conviction that the new structure should grace the heart of the city’s foreign commerce, where New Orleans had welcomed explorers, visitors and trade for almost 250 years, embracing the Mississippi River at the foot of Canal Street.

It worked, and International House selected noted architect Edward Durell Stone, born and educated in Arkansas, but a convert to Modernism after a tour of Europe and North Africa following college, to design the tower on the river.

Enamored of the International Style, Stone collaborated on the original buildings of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Waldorf-Astoria hotel ballroom and Radio City Music Hall, where he began to overlay the stark surfaces of Bauhaus-style architecture with decorative touches that would have shocked such purists as Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. Perhaps best known for his stunningly-simple U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, with its decorative sun-shielding screens, Stone was a star, controversial but ascendant.

The first design for the trade center was a square, 19-story building topped with an open colonnade and decoration that, in architectural renderings, seemed to echo the mosaic adornments of towers at the University of Mexico in Mexico. A wide surrounding plaza, stretching to the river, was tiled in a pattern suggesting the lines of latitude and longitude in a Mercator map of the world. In concept, it was closest to Stone’s marble-clad 2 Columbus Circle invocation of a Moroccan palace.

World Trade Center Association founder Paul Fabry poses defiantly in front of the WTC tower just days September 11, 2001. (Photo by G.Andrew Boyd, nola.com)

The final design, a 33-story tower topped by a revolving restaurant — later a lounge — dubbed the Top of the Mart, offered views of the river, Vieux Carre, business district and Lake Pontchartrain and served as a visual link between the river and the lake, the city’s defining bodies of water.

Often described as cruciform because of its four wings, the shape actually represents the four points of the compass, and Stone oriented the building to these points, emphasizing the concept of trade across the world.

Dedicated on April 30, 1968, the tower was a focal point of the celebration of New Orleans’ 250th anniversary celebrations, which attracted dignitaries from around the world. And it served as a bold vertical complement to the ingenious, river-flow-echoing Rivergate convention center, now demolished. With the gilded statue of Joan of Arc, placed later, the combination echoed Jackson Square with its equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson.

That same year, Paul Fabry of International House met in his Vieux Carre residence with representatives of several countries to form the World Trade Center, of which the new International Trade Mart was the first member structure. Twenty years later, Bob Carr, then heading International House, suggested changing the name to World Trade Center when International House and International Trade Mart merged in 1968.

Today, the World Trade Center stands alone and forlorn, its brilliant counterpoint, the Rivergate, replaced by the mock-historic Harrah’s Casino.The design-defining but frequently-maligned aluminum louvers that actually function to screen out the sun’s rays are a clever combination of Le Corbusier’s brise soleil and Vieux Carre louvered shutters; they undoubtedly could be spiffed up. The unbuilt balcony-level grand staircase, designed to span the railroad tracks that isolate the tower from the river, could be redesigned and installed to link the tower to the riverfront.

The World Trade Center deserves to, and can be, saved.

Even if historic tax credits are used for redevelopment, the exterior could be freshened up and design flaws mitigated. Modifications might be made to the spindly columns that support the wrap-around balcony that, with the original staircase finally in place, would make an airy promenade with views of Canal Street, the edge of the French Quarter and the river itself for visitors. The mezzanine level inside could host foreign trade delegations, as the original building at Camp and Common did.

Even as the lobby of an upscale hotel and residence, the upper level could become an international bazaar; and celebrations of national holidays could be held in the spacious lobby or the Spanish Plaza — or any replacement that might be developed.

It’s a question of respecting the concept of “stored energy,” the idea that each building contains the stored energy used to create the building materials and the labor to construct it. Demolishing a structure wastes that energy, as well as energy necessary to bring down an iconic structure like the World Trade Center.

Better the evil we know than the one we don’t. The World Trade Center, though imperfect, embodies not only stored energy, but also the aspirations of a city once known as The Gateway to the Americas. To lose it would be to lose history, heritage, and the belief that New Orleans can do great things.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.