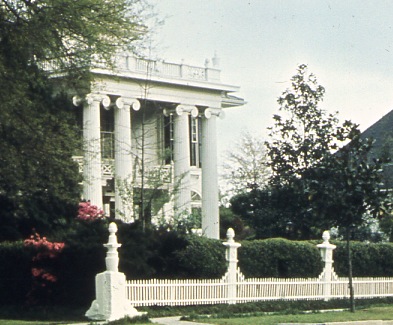

The Turner House in Hattiesburg (Photo by Ursula Jones)

“You’re he!”

The young widow who approached me after my illustrated lecture, “Temples in the Canefields: Louisiana’s Historic Plantation Houses,” at the Hattiesburg Area Historical Society three decades ago, was wide-eyed, but soft-spoken.

“I beg your pardon … who?”

“The Confederate soldier who rescued me in my dream last week. Your face. The way you talk. Everything.”

I sensed danger ahead. As owner of Madewood Plantation House in Napoleonville, Louisiana, an 1846 National Historic Landmark Greek-Revival mansion, I’m automatically suspect as an historical anomaly. At the elegant reception that followed the talk, held in the candle-lit garden of a turreted Queen-Anne-style mansion in the center of Hattiesburg, I made off-hand comments that I hoped would betray my growing liberal bias.

I’d taken the Southern Crescent from New Orleans that morning, watching the sun rise over Lake Pontchartrain as I poured real maple syrup over pancakes cooked on the train’s iconic wood-burning stove.

At the historic Hattiesburg train station, there was only one car in the parking lot, a white Rolls-Royce sedan, with a man in chauffeur’s coat scanning the platform for the expected arrival.

Stately interiors mirror the Turner House lifestyle. (Photo by Ursula Jones)

By the time I’d settled into the stolid Victorian armchair in the parlor of the stately Turner house, the chauffeur had donned a white jacket to serve me coffee, holding the heavy silver tray just so as I poured from the footed pot, adding sugar and a splash of steaming milk.

The owner, James Turner, made a sweeping entrance, and soon it was time for him to take the wheel of the impressive vehicle for a tour of the town that ended with lunch at the home of a prominent banker.

The men were taking a long lunch break from the world of finance and took their seats at the long table after pulling out dainty tufted chairs for their wives. But before dessert — the first time I’d encountered poached pears encased in crisp, warm chocolate sauce — it was time for them to depart.

After talk of the evening’s lecture and local social and cultural events, our hostess suddenly arose. Conversation ceased.

“I think we all should have a lovely lie-down before Mr. Marshall’s talk, don’t you?” she purred.

I was escorted to my personal lie-down at the Scottish Inn motor hotel, where a room had been reserved for me. At first shocked by the over-the-top decor of the choice room, I began to luxuriate in the red-velvet environment, staring into the immense round mirror on the ceiling that mimicked the plush round bed in which I lay. Fresh flowers and a box of chocolates — though I’d not planned an assignation — completed the scene.

“Interesting place, this Hattiesburg,” I thought.

The next morning, after a Scottish “Thrifty-Value” breakfast, I slid into the back seat of the classic transport, so out of place in this particular parking lot, and was driven to the nearby Crosby Arboretum for a visit with Dorothy Crosby, whom I knew as a fellow opera lover in New Orleans. She was renowned for driving her ship-like amber Cadillac station wagon — another first for me — regally around New Orleans like the grande dame she was.

Then it was time for the train home, after collecting my luggage from the Turner house. But, shocking news: The train was two hours behind schedule.

No problem. The butler filled a stylish wicker hamper with freshly-made sandwiches and iced several bottles of champagne. We sat on benches on the platform of the historic depot, eating and drinking as if we were guests in the Royal Enclosure at Ascot.

Is it any wonder I always end this tale by insisting to quizzical listeners that Hattiesburg, Mississippi is the most gracious, sophisticated place on Earth?

The only time I wondered if that young lady might be sane was as I was falling asleep, staring fixedly at my visage, through cocktail-hazed eyes, in the all-encompassing ceiling mirror.

But if I saw anything at all, it was a thrifty Scotsman, swaddled in a red-velvet bedspread, not a gallant soldier.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.