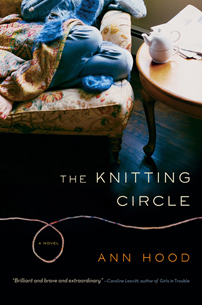

A book on authors who knit was not what I expected when I walked into the panel An Examined Life: The Mysteries of Memoir but as Ann Hood pointed out “knitting is a metaphor for life.” Both her personal obsession with knitting and her novel The Knitting Circle grew out of trying to cope with her own tragic loss of a child. She also authored a memoir about the loss of her daughter Grace, COMFORT: A JOURNEY THROUGH GRIEF but knitting proved to be her best coping mechanism “After my first knitting lesson I realize I got through two-and-a-half hours without crying.” She soon discovered other authors who knit, and decided to pitch her new book Knitting Yarns: Writers on Knitting. She took her editors grunt when she pitched the idea as a yes, and ended up with 27 essays by authors who knit and how it changed their life. When she read her own audio book, she imagined the “fedora-wearing Brooklyn hipster” who was her audio engineer must have thought he had drawn the worst assignment ever, but she said he confessed to crying by the end of the four days by the stories he heard.

A book on authors who knit was not what I expected when I walked into the panel An Examined Life: The Mysteries of Memoir but as Ann Hood pointed out “knitting is a metaphor for life.” Both her personal obsession with knitting and her novel The Knitting Circle grew out of trying to cope with her own tragic loss of a child. She also authored a memoir about the loss of her daughter Grace, COMFORT: A JOURNEY THROUGH GRIEF but knitting proved to be her best coping mechanism “After my first knitting lesson I realize I got through two-and-a-half hours without crying.” She soon discovered other authors who knit, and decided to pitch her new book Knitting Yarns: Writers on Knitting. She took her editors grunt when she pitched the idea as a yes, and ended up with 27 essays by authors who knit and how it changed their life. When she read her own audio book, she imagined the “fedora-wearing Brooklyn hipster” who was her audio engineer must have thought he had drawn the worst assignment ever, but she said he confessed to crying by the end of the four days by the stories he heard.

An Examined Life covered a lot of ground, some of it at the edge of memoir, but the four authors on the panel–Hood, Blake Bailey, Lila Quintero Weaver and Emily Raboteau–all authored recent books that attempt to reclaim a part of their lives. Bailey’s story of his brother, who fell into drugs and died by suicide, is the closest to true memoir. “Scott was the better brother, the more promising of [us] two before he started to go off the rails. We should have landed in the same place and we didn’t and I decided to write [the book] to figure out why.”

Quintero Weaver’s Dark Room: A Memoir in Black and White, a graphic-novel approach to a tale of growing up a Latin American immigrant in rural Alabama during the civil rights movement is, by her description, as much a book about place: what Odd Words likes to call a geo-memoir. Her father was the town’s only photographer, but the illustrations in the book are all Quintero Weaver’s. Raboteau’s exploration of African-Americans who moved to Israel and Africa looking for a place that felt like home was driven by her own desire to find her identity as a bi-racial child of the 1960s who grew up in New Jersey constantly answering the question “where are you from?” and ends with a return to Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, the town her parents fled after her grandfather was lynched.

Solace and closure, the discovery of one’s real place in life and the world, are the meat of memoir. Only Bailey’s and perhaps Quintero Weaver’s books would be easy to file in the bookstore under memoir, but all drew deep on the author’s desire to understand critical events of their own lives.

Asked by moderator Nancy Dixon how their families’ reacted to their books, Bailey replied, “it was brutal. If you’re the sort of person who frets about what your family will think you’re in the wrong genre.” Quintero Weaver responded about the reaction of the people of the small Alabama town she writes about. No one would tell her exactly why they didn’t like the book but suspects “they want to move on.” Marion was at the center of the Civil Rights movement and the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson while the Southern Christian Leadership Conference was in town led to the historic march from Selma to Montgomery. She heard second-hand that the president of the Chamber of Commerce said, “we don’t want her book in our town.”

Hood summed up what is required of the memoir author: “You have to write like you’re an orphan.”

Earlier in the day, novelist Justin Torres spoke of his own approach to putting a life’s experiences down into words in his bildungsroman We The Animals,the story of his own gradual “orphaning” from his family. “When I started, I was writing back to my family…I’d been ejected [for coming out queer] and the original motivation was anger.” Torres brief, 125-page tale of three brothers is fictionalized, although after reading it one brother told him of an episode, “I remember that.” “You can’t,” Torres replied. “I made it up.” Later he added, “I did not write my memoir. This is not my life. This is the emotional texture of my life.”

Asked toward the end how his family initially reacted to the book, Torres said “I hurt them. You don’t tell family secrets. I don’t know that I did the right thing but I believe in art.”

Torres’ interview with Festival Programming Director J.R. Ramakrishnan was titled “The Super Sleek Novel” and a great deal of the discussion was about the brevity of the novel and how it achieves its goals in such a short space. When he went to New York, every publisher he met with told him they loved the book, but he needed to write another 100 pages. Novels are supposed to be 250 pages long, he was told over and over again. The last editor he met with also responded positively to the book, and Torres told her, “but you want me to write another hundred pages, right?” but she said no.

The book unfolds as a series of very short chapters, each unveiling one small aspect of the character’s life growing up with his two brothers. “Super compressed, super distilled chapters: that’s what works for me. I could be very poetic and still get to the point…little movements that were so complete and yet captured the world. What I really like about the short form is you are always creating tension and then there is a little climax.” Most of the chapters begin in the first person plural before moving to the first person. “The idea of we is we feel a collective personality as children, [my brothers and I] had this non-verbal way of understanding each other” and as the book progresses the characters gradually lose that, subtly depicting the gradual unraveling of childhood and Torres’ own place in his family.

Asked if he could write with the same passion if he were not writing from his personal experience, Torress said, “I think that what is true is the kind meaning you make out of your experience. We’re all thrown here on this earth and there’s no meaning, it’s chaos. A lot of writers are communicating the way they found meaning in this world. That’s inherently personal You have to find a way to create meaning. I choose to write from personal experience. I choose to keep it close. Also, because I feel [as] a mixed-race, queer, working-class dude, it’s political in a lot of ways. I’m really interested in intersectionality, I’m very interested in the ways i which my various identities are constructed socially…its absolutely possible to due to that in fiction” as well as writing from personal experience.

Torres never names the parents in his book. “They really are archetypes of our ideas of masculinity and femininity. I made a myth out of them to essentialize them….[t]here is a lot of opportunity for projection” in the book, and he says he frequently is told by readers that’s exactly what my experience was like. “There’s such a universal element in the book” a lot of people see their own families and experiences in it. “I hope the book breaks people’s hearts because we need to keep breaking people’s hearts.”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.