What is it with this whole notion of Southern belles? Why does only this region of the country seem to define gender identity through beauty and femininity?

What is it with this whole notion of Southern belles? Why does only this region of the country seem to define gender identity through beauty and femininity?

An 18-inch waist … seriously?

These are questions that historian Blain Roberts has been asking ever since she chose the topic as her college thesis at Princeton University.

“It was the first time I was around men and women from other parts of the country,” says the small-town Louisiana native. “And the first time I was around women who didn’t wear makeup. During my junior year, a friend from Boston said to me, ‘Southern chicks are hot.’ I realized that a lot of how we identify Southern women is about perception. And I kept circling around this Southern belle thing.”

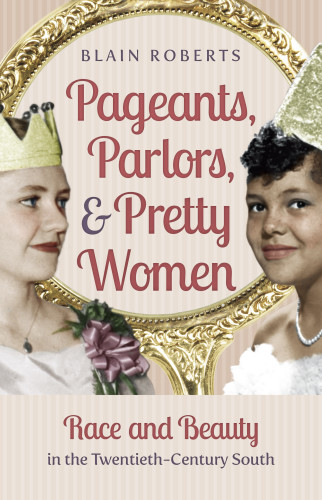

She turned her research into a doctoral dissertation at UNC Chapel Hill, and, most recently, into a book. “Pageants, Parlors and Pretty Women: Race and Beauty in the Twentieth-Century South” looks at the way beauty is enmeshed in Southern culture. Now a history professor at Cal State Fresno, Roberts continues to be fascinated by the way skin creams and hair treatments keep popping up in any sociological study of the South, particularly when it comes to racial divides.

Technically, the term “Southern belle” applied only to those antebellum unmarried daughters of wealthy white Southerners. “Southern lady” referred to her older married counterpart. There were not, says Roberts, a large number of either.

“New Orleans would have had belles and ladies, but most Southern women were neither. They came from a much more modest background,” explains Roberts. “Yet the perception is that everybody in the Old South was a belle – either a Scarlet or a Melanie. People love the idea of the ruling elite. But it’s pretty problematic to romanticize that.”

The underlying identifier of Southern belle, you see, is based on race: As Roberts puts it, “she’s white, sexually pure, and put on a pedestal.”

Black women, by contrast, were perceived as passionate and sexy, the so-called Southern “Jezebels.”

“These ideas determined how people acted and treated women,” says Roberts. “And it gave license for abuse.”

Beauty, she elaborates, is largely about power – racial power, class power, gender power. And as the 20th century blossomed, women began to test that power in terms of their looks. It was, after all, the era that saw the introduction of cosmetics.

“Beauty products started to take off in the teens and ‘20s,” Roberts says. “For so many women, both black and white, it was an exciting new product.”

New Orleans, says Roberts, would have been at the forefront of the trend.

“For one thing, it would have been a place where women could visit barbershops. Sophie Newcomb women would have been getting their hair bobbed, trying makeup, smoking cigarettes. It’s a great example of early adopters.”

Beauty culture for black women was changing, too, Roberts says. But it wasn’t a matter of emulating white looks. When beauty pioneer and black businesswoman C.J. Walker came up with a way to style and grow healthy hair, she did so because “she wanted black women to look and feel good about themselves. It was the first iteration of black pride.”

Walker and others like her felt that lessons on parenting, housekeeping, fashion and beauty would give black women the values and behaviors that would help them become middle class.

“I call it the esthetics of respectability,” says Roberts. “In attempting to look like everyone else, black women were trying to undo the logic of racism, which is built on being different.”

A historically black college like Dillard, then, had a mission to mold black men and women to be presentable, respectable people. Accordingly, there were strict rules about dress and deportment.

“Being homecoming queen at a place like Dillard would have been huge,” Roberts says. “She would have been held up as the ideal for black women.”

In the early 20th century, other cultural elements were changing for both races of women: They could vote, get an education, go to work. In those early days, cosmetics were part of a liberating trend. Ironically perhaps, by the 1960s beauty products would be seen as a way to keep women down.

Along the way, Southern women, Roberts maintains, evolved differently from their counterparts elsewhere in the country. Both the history of slavery and racial segregation and the relative rural nature of the area played roles: “It made for more conservative views toward acceptable and appropriate behavior for women.”

Beauty pageants were (are) huge down South.

“Part of that has to do with how rural the South was,” Roberts says. “Local 4-H and extension services started having better baby contests and adolescent healthy body contests that fostered competition. And once they figured out that young women can be used to sell everything from peaches to cotton, they took off. There were festival queens all over.”

There are still festival queens all over — from Pecan Princess to Cajun Seafood Queen. A friend once mused that the quintessential Southern identity crisis can be summed up in the idea of the Shrimp and Petroleum Festival queen, two seemingly incompatible products.

But that’s the South for you. Southern belle and 18-inch waist or no, it’s hard to pin down just what identifies the beauty — literally and figuratively — of the region.

And it’s never, perhaps, a bad thing to be from an area whose women are widely considered to be hot.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.