Artist Bob Graham doesn’t dispute that Mardi Gras is one hell of a good time, but it’s light, particularly the ethereal, otherworldly light of a night parade, that gets his heart beating and his brush moving. Graham’s romance with light is almost palpable, conveying the richness of the moment with a laser-like brilliance that draws the viewer into not just the spectacle, but also the richness of the glow that suffuses and radiates from the luminescent hues on his canvases.

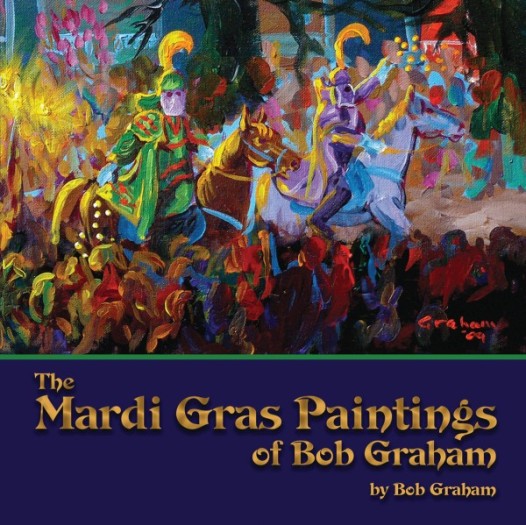

All this is apparent in a new book, The Mardi Gras Paintings of Bob Graham, scheduled for release by Pelican Publishing on February 1.

Graham traces his fascination with light to his mentor, Henry Hensche, with whom he studied for 17 years, from 1970 to 1986, in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

“Henry knew more about color than anyone else I’ve ever met. He was a master of placing color against color for expression,” Graham said. “And he’d manufacture colors that no one else had, to match his insight into how colors relate to each other.

“He was a crusty old Cape Codder when I met him; but he took me seriously, and it was through him that I learned how to record the quality of light.”

Graham considers himself, first and foremost, a plein-air painter, a spiritual descendant of the 19th-century French artists who strove to capture life directly by painting outdoors, rather than in the studio, to give freshness and immediacy to their work.

But Graham maintains that this method is not just about pretty landscapes, Monet’s views of buildings at different times of day, or working-class parties along the Seine. The cold, flambeaux-enhanced light of a night parade, embracing the colors of floats and participants alike, might be described as tinted or tainted air, but to Graham it’s all the same. The artist is there to enhance and convey the experience, and light remains the pre-eminent force, under brilliant sun or wistful moon.

The principles remain the same — a quick reaction, you strive to recreate the emotion of the moment.

“Each painting is a poem with with no words,” Graham explained. “You can feel how the color transmits the feelings and emotions.

“There’s a great similarity between a yogi and an artist. You enter similar mental states. I do a lot of this,” he said. “It’s a discipline that frees the mind to find order” — even in the chaos of a Mardi Gras parade, one can assume.

“The painting of light is as important as the details,” Graham added. “I want to give the feeling of the parade. Too many details get in the way of the experience of actually being there.”

But there’s calculation in the madness and certain practicalities that must be observed.

“You have to get in there to, to mingle and feel the mood, get the colors right. But you also have to be able to get away quickly, because cops come along and chase you away. It’ll make you lose your mind, but you just have to deal with it. You have to keep in mind that you’re there to capture the light, and that what you’re doing is all about light.”

Graham also finds lessons about the evocation of light in the paintings of controversial mega-artist Thomas Kinkade, who died in 2012. While Kinkade has been excoriated by critics for endless depictions of idyllic pastoral scenes designed to appeal to the masses, Graham looks beyond Kinkade’s subject matter to what he views as “the perfection of light rendered quickly. He didn’t reproduce the light you see in a particular scene in nature, he did it by formula, but that’s valid,” Graham maintains.

Similarly, Graham said, “I’m into the visual aspect of Mardi Gras. You have to choose colors; you have to make artistic choices to create a work of art, rather than just create a visual record. Sometimes I have to alter the actual colors of a float to make the lighting right, to convey the actual feeling.”

“I don’t have particular recipes; I react to the moment, but there’s a method to my madness. Flamboyant colors? It’s wonderful to use them, but there still are rules to the method, and I have to obey them. And sometimes I’ll use a three-quarters view of a float, alter the angle to give more vivid information about the parade.

“Don’t forget,” he cautions, “at Mardi Gras, we’re faking it to have a good time, to escape from reality. Fake royalty is what keeps it all going.”

While light remains paramount in all these paintings, sometimes Graham admits he goes for accuracy.

“I’ll tighten up when I want to be more precise with something like the side view of the Orpheus parade. This works because my paintings are also about binging out the fun in a parade, to simply convey the scene and let people interpret the parades themselves.”

In one painting, detail is the equal partner of light.

“To paint Zulu was stressful for me,” Graham said. “It’s a great parade to paint. You have great elements like Big Shot and the Witch Doctor. But to paint Louis Armstrong (who reigned as King of Zulu in 1949) — man, to paint his face, that was a challenge. I had to be more detailed than I like to, but I was determined to get it right.

“After a certain point,” Graham maintains, “it doesn’t matter how you did it. The result speaks for itself.”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.