I’ve worked with Brian Boyles since we met at Handsome Willy’s in 2008. We’ve worked City Council DJ Happy Hours, cross-generational panel discussions, yard parties, music festivals, and many, many Saints games. His new book, New Orleans Boom and Blackout: 100 Days in America’s Coolest Hotspot, is a nonfiction account of the 100 days preceding the 2013 Super Bowl. The book depicts the city in the throes of developments economic, infrastructural, and political as New Orleans rushes to meet the expectations of its first true post-Katrina national debut.

Brian is currently the vice president for content for the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, where he has directed public programming since 2007. His writing has appeared in Oxford American, Vice.com, The Classical, Offbeat, The Lens, The Brooklyn Rail, and SLAM.

He will present his new book at a Happy Hour Salon from 6 – 9 p.m. on Thursday, Feb. 26, at the Press Street HQ (3718 St. Claude Ave.). The event will also feature best-selling novelist Jami Attenberg.

Room 220: When you started this project, you knew you wanted to write about New Orleans’ preparations for the Super Bowl, but you didn’t know exactly what form the work would take. Let’s talk about how the desire to write about the city became Boom & Blackout.

Brian Boyles: I started to write things down associated with the themes I had in mind probably as early as May 2012. I’d been reading a book about Beijing called Beijing Welcomes You by a guy named Tom Scocca,who writes for Gawker. He had moved there with his wife just as the Olympics were coming down, and he said that it was a really crazy city to live in because just as you learned your way to the store, or to the stadium, or to your gig, something would get torn down and the whole way would be completely reworked overnight. That’s how fast change was happening warren to warren in Beijing, getting ready for the Olympics.

I knew that wasn’t what was happening here. I knew it wasn’t happening that fast, and that there was a deadline—the Super Bowl. So I began with the idea that there was a time when I would stop recording. I really do believe you can go on recording here forever.

So I started at the Mayor’s State of the City Address when he launched NOLA FOR LIFE. That summer I spent time on Bourbon Street, writing an article for the Oxford American, and at that point I got the idea to really focus on the people who would be working on the event. Originally I thought that it would be, you know, “Nine People and Their Stories,” but it was just too difficult to catch up with the people, to give them their just due. There were so many more storylines than I thought there were, and so by September I decided I would just watch the next 100 days and focus on what the city was doing in preparation for the Super Bowl. There were events and press conferences, and that was enough of a scope.

Now I had a solid timeline and a focus. As I got to the end it was just fast and furious, and the quality of my recording varied. But I’d signed the book contract by December and we had a baby born on Christmas. At that point I realized I had to focus on the history. I didn’t have time to re-interview people, to reconnect—the time for that work was gone. I had to reshape all those anecdotes via research, work that I could do from home.

Rm220: You’ve been working in the public history and culture business for a while. What were some of your previous projects that best prepared you to handle Boom & Blackout?

BB: The obvious one was the Mayor’s Panel, which gave me a thorough background in the 20th century history of the city. A big deal was working for SLAM. I wrote for them for about three years, and I went to Hornets and then Pelicans games all the time. Especially during the Chris Paul era. Going to all those games gave me a sense of the arena, the feeling of writing while sitting in baseline seats.

That was like getting a promotion from writing on the subway. I’ve been trying to get better at writing in motion my entire life. This project was the O.J. Simpson Hertz commercial of that mode of work.

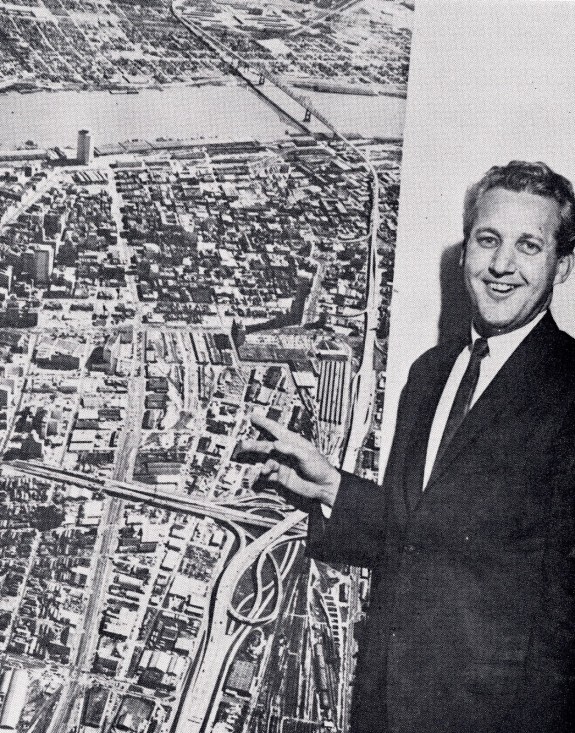

Moon Landrieu gives a presentation advocating for the construction of the Superdome in 1968 (photo source). “Construction of a multi-purpose domed stadium may be bold but not unrealistic. Such a facility is an investment that will mean additional income for everyone in the city and state,” he said.

Rm220: How did you determine the basement for your research? With a 300-year history of recurring themes, why did you begin yours in the 1950s?

BB: That was another clear time of transition—of a new New Orleans. Before WWII, it was a very different city, a different state, and a different country. That period is also geographically important to the story, because I needed to describe this strip along Loyola Avenue, and in the mid 50s and 60s, that neighborhood was being transformed.

At the same time, professional sports in New Orleans are taking off at that time—the Saints, the Superdome, Moon Landrieu. I needed this foundation to explain what was currently happening regarding the Super Bowl. I needed to paint a clear picture of the 60s and early 70s because the opening of the Superdome is fundamental to understanding that part of downtown.

From there you get into the Oil Bust. Then the 1984 World’s Fair—you can’t talk about the Super Bowl without talking about the World’s Fair. I felt at times it was cumbersome to talk about the fair—so many memories of it are heavy, but they are warranted. All the attention that’s paid to the World’s Fair is warranted.

There was a cat who didn’t make the book—he’d posed as a car dealer trying to invest in some bars during the World’s Fair, and they found out later he was a narc. Dean Baquet wrote the article. That was the cool thing about doing the research, which was at least as much fun as writing the narrative parts. It is a dense history, and to be able to take some time to go through so much content, it was a treasure.

Rm220: How did you determine the geographic boundaries of Boom & Blackout?

BB: Just as there were 100 days, the Hospitality Zone had been declared in the CBD and downtown. That worked as an advantage, because there was a clear geography of sanctioned, tourism-related events. It allowed me to focus on a few areas and freed me from having to define other neighborhoods. There was the airport, which was the gateway to the whole show, but for the most part everything was within walking distance of my office.

I needed limitations, and the book was an exercise in selecting the things I felt resounded during this period. There were things going on all over, but the fight was not to make the book a series of successive cymbal crashes, because there was really that much going on in the city at the time.

Rm220: You deal with all manner of people in Boom & Blackout, and the result is a broad portrait of New Orleanians involved in the hospitality industry as well as the public sector. What was it like to move among so many different classes of people?

BB: It’s humbling and invigorating to see how many things are being done, how much effort is being taken to sustain the industry. I talked to whomever: people working, volunteers, people just cruising along. But most of the New Orleanians I met were working—I like them; I’m one of them. That is what I found invigorating. I liked what I saw. Even the people that I thought were doing straight up wrong— fill in the blanks— they were working.

Rm220: What were some of the strange situations you encountered?

BB: I tell you what was the most chilling. After the parade that kicked off the Loyola Streetcar, I got a call from two New Orleans cab drivers and they told me to meet them at a hotel on Gravier. I took the elevator up to the eighth floor and was standing in a little breakfast area outside the conference rooms. The woman who’d called had helped to organize the taxi boycotts, and she met me in the breakfast room. She said she’d wanted to bring me in, that they were having a union meeting.

There were three guys in suits who were like, “Who is guy in hoodie and a backpack?” They said they needed to finish their meeting, and in a half-hour they came back out and told me that they were basically staring down the barrel of Super Bowl week, and it hadn’t done anything good for them.

They were getting beaten up by violations of the new cab ordinances. I mean, getting beaten to hell, and that was chilling. I mean, if this thing is growing, why do these people have to lose their jobs?

Rm220: While you were writing Boom & Blackout, were there any scenes—any luminous details or images—that really clarified the whole thing for you? Any visual metaphors?

BB: The asphalt on Royal Street. Seeing what a bad job had been done. This wasn’t Beijing—it wasn’t at some haphazard pace. If you weren’t driving, you wouldn’t have even noticed it. Except that it flooded, and it had never flooded in that street before. In 2018 it will have been three hundred years, and that street shouldn’t have ever flooded.

Rm220: In those seven or so months of research, was there any particular data or history you came across that really surprised you? Something truly enlightening?

BB: Reading about how Lester Kabacoff really hated the World Trade Center and the Rivergate, I think that was a moment when things just made sense to me. It was late in the research, but I haven’t been real confused since then.

Rm220: Let’s list the books essential to writing Boom & Blackout.

BB: I mentioned that Tom Scocca book, Beijing Welcomes You. Ed Haas’ biographies of Chep Morrison and Victor Schiro. A.J. Leibling’s Earl of Louisiana — knowing about Huey Long, in general. Richard Campanella’s books. There’s a guy named Mark Souther, and his book New Orleans on Parade is a must-read for anyone writing about tourism in the city. I read it in 2011 – 12, and it was a big help.

Just as I started to finish the book and get into the edits, I read David Simon’s Homicide, and it was cool to get an injection of high quality as I was trying to get over the finish line. That book helped me focus much more than if I’d still been reading the newspaper at that point, or still trying to keep up with current events. He was not afraid to have a voice, and I found myself getting my voice only in the last weeks.

Rm220: You’ve said this book is not journalism. Why?

BB: I’ve never been able to have remove the way I’d need to have remove. I’ve always used music or events to express my ideas and opinions. I knew early on I wasn’t going to shortcut my way into journalism. I have a good layman’s history of New Orleans—I’ve read a lot, done interviews, hosted panels, etc. I’ve been surveying and interacting with New Orleans history for a while. People wrote really great stories as this stuff was going on, but no one had been able to synthesize all these events. I think that general knowledge was what I had to say, and that’s not journalism.

This article was originally posted by Press Street: Room 220, a NolaVie content partner.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.