Editors at literary partner Press Street: Room 220 recently took a stroll across the internet, and came up with this roundup of recent New Orleans- and Louisiana-related articles:

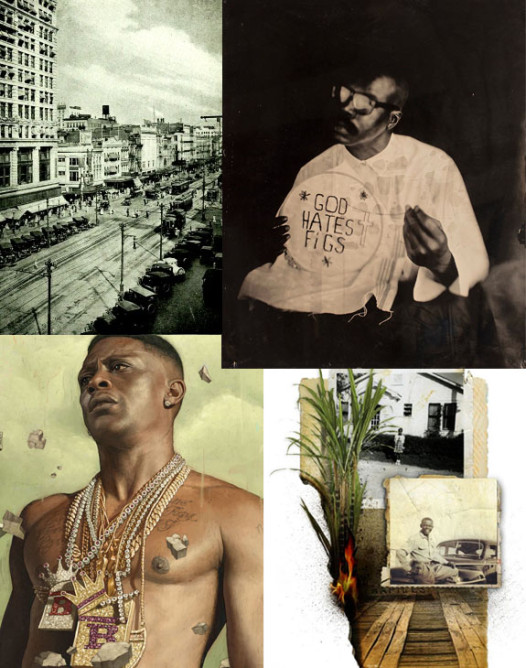

Clockwise from top left: A picture of Canal Street the LARB editors thought evoked ‘crime’; tintype photograph by Kevin Kline; collage of images by Jen Renninger that accompanies “We A Baddd People”; illustration of Lil Boosie by Rory Kurtz

Lil Boosie longread

At Playboy, New Orleans journalist and criminal mitigation specialist Ethan Brown breaks down the pivotal moment in which Baton Rouge rapper Lil Boosie finds himself after being released from prison, having one of his songs serve as an anthem for Ferguson protestors, signing contracts, dropping records, and (probably) deciding not to live in New Orleans. (Did you know that New Orleans City Councilman Jason Williams was the attorney who helped Boosie beat his murder rap and get out of Angola?). An excerpt:

This scene at the Cajundome is overshadowed by outrage building 700 miles away in Ferguson, Missouri as a protest movement set to become the story of the year gains steam. Given Boosie’s release just seven months earlier, one might assume it would take time to rebuild his public profile, but in August, Boosie’s “Fuck the Police” became the soundtrack for the demonstrations against the police shooting of Michael Brown… Little could he have predicted the track would contribute to dozens of arrests in Ferguson, including the one captured in an August 23, 2014 YouTube video in which a protester standing outside a McDonald’s blasts Boosie’s “Fuck the Police.” He’s quickly swarmed by officers led by Missouri State Highway Patrol captain Ronald Johnson, whom Time magazine dubbed the “star of the Ferguson crisis” for his ability to calm angry crowds. As the protester is arrested, someone yells, “What law was broken?” Johnson responds that the man was “inciting”—as though publicly playing Boosie’s music could bring about riots.

Anti-anti-New Orleans exceptionalism

At Lousiana Cultural Vistas, New Orleans writer and Room 220 contributor C.W. Cannon takes on the recent trend among academic historians to rail against “New Orleans exceptionalism”—the notion that New Orleans possesses characteristics that make it distinct from other places, special, operating according to different rules. These historians argue that such a sense of exceptionalism has historically served as an excuse New Orleanians use to explain away its ills. But, Cannon retorts:

One of the biggest problems with this [anti-exceptionalist] approach is how tone deaf it is to the aspirations and possibilities of local identity. New Orleanians have broken into the two camps of Americanist and exceptionalist for centuries, yet now we supposedly have an opportunity to end this ideological history by amputating one side of the dialectic. But why would we want to do that? Why is our rich local mythology seen as the problem? Can it really be that our little city’s dream of an exceptional identity is a greater contributor to inequality than capitalist ideologies of unrestricted free enterprise, individual initiative, and social mobility? If we could manage to excise our deeply ingrained sense of special identity, and see ourselves more like a smaller version of Houston, Atlanta, Jacksonville, etc, who could possibly believe that this cultural mutilation would lead us to overcome the ingrained injustices that are part and parcel of American capitalism everywhere?

Kevin Kline’s tintypes

At BOMB, New Orleans author and Room 220 friend Zachary Lazar pens an homage to the work of his buddy Kevin Kline, whose new series of tintype photographs document a love affair within a city—and maybe a love affair with a city.

Perhaps nowhere in the world is the line between beauty and kitsch finer than it is in New Orleans. The city is famously awash in beautiful living culture—brass bands, sissy bounce, gutter punks, Mardi Gras—point a camera anywhere and you’ll get an arresting image, though it will probably be one of a thousand just like it… The remarkable thing about A Stranger to Me, Kevin Kline’s new series of tintype photographs, is how they manage to say something new about the city, carefully refracting its essentials, as in Lou Reed’s Berlin, through a personal story—a love story. Kline has made twenty-one images of his longtime partner Brian Waitman, who enacts poses representing significant moments in their sixteen-year relationship. Waitman is “Mr. High Pockets,” the big-spending night crawler in a top hat, and he is a parody of a white magistrate in a wig of cotton balls, and he is a proxy for Trayvon Martin in a hoodie. He is a prisoner in stripes, a saint in a hair-shirt made of beer can tabs from beers actually emptied by him and Kline, and he is Venus de Milo as a black man whose vanished arms become an emblem of a gentrified city that has grown significantly whiter since Katrina.

New Orleans hard-boiled

At the Los Angeles Review of Books, New Orleans author, bookseller, and Room 220 contributor Michael Allen Zell confronts the question, “What is the place of and necessity for crime fiction in one of the most dangerous cities in the world?” In the course of his answer, he provides a rundown of essential crime novels and novelists who work in the world of New Orleans and its history. Zell is the author of Run Baby Run, which he describes as a straight-up New Orleans crime novel, forthcoming this year from Lavender Ink.

On the one hand, crime is so pervasive and affects every level of society such that any New Orleans novel with range is a de facto noir book or at least contains stock characters of the genre. Examples of this include the B-girls of John Kennedy Toole’s classic Confederacy of Dunces, the criminals in Louis Maistros’s magical realist The Sound of Building Coffins, and the arsonist murderer of Baron Ludwig von Reizenstein’s mid-19th-century urban gothic The Mysteries of New Orleans. The excellent Yellow Jackby Josh Russell and the Liquor series by Poppy Z. Brite (now Billy Martin) also contain more than a few wrongdoers. On the other hand, today more than ever before, “everybody all day long knows what is happening.” This leads to an increased interest in well-researched nonfiction about New Orleans: Chris Wiltz’s (also known for her Neal Rafferty mysteries) The Last Madam, Matthew Randazzo and Frenchy Brouillette’s Mr. New Orleans, and Orissa Arend’s Showdown in Desire come to mind in the realm of true crime. But what does it mean for the city’s contemporary crime fiction?

Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah’s Louisiana kin

This one is more accurately described as “recently re-read” than recently read, but it’s not that old—it came out in the Virginia Quarterly Review last summer—and we liked it so much the second time around we feel compelled to share. “We A Baddd People,” beautifully recounts a story told to Ghansah by her grandmother about the first of her eight husbands, whom she met and fell in love with in her hometown, Alexandria, Louisiana. Ghansah is perhaps best known for her non-profile of Dave Chappelle, “If He Hollers Let Him Go,” which was a finalist for the 2014 National Magazine Award.

My grandmother wants to tell me this story so it drives, so I listen and stop thinking I know it already. This is her correction, because they don’t teach you nothing in those schools, except lies and that we were weak, she says. And she tells it like she is losing her breath, like time won’t grant her the seconds to speak it. Such strange things can trigger her into talking, dreams about her stillborn twin, the scent of Chantilly perfume or damp days in mid- October, when lightning cracks and she wants us to cut the lights and be still. Only then does she want to tell about the beginning, about the baddest people who ever walked the Earth, and on those days I might sit at the foot of her mattress and stick my fingers into the orange, green, and brown frayed knots of her afghan blanket and listen…

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.