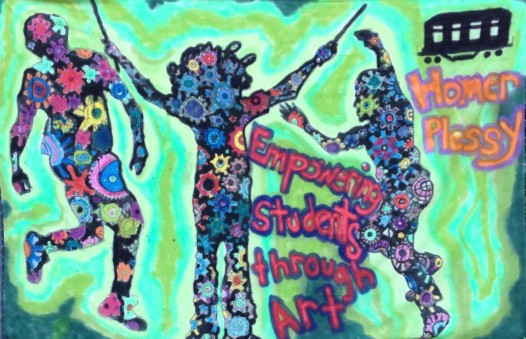

A colaborative piece by third-graders at Homer Plessy School is representative of the 1-year-old school’s project-oriented focus. (Photo: plessyschool.org)

This weekend, 5000 arts educators are meeting in New Orleans, at the National Art Educators convention, to talk about the ways in which arts in the classroom can create better critical thinkers for our more complex digital age. More and more educators are touting the benefits of an arts rich education.

But do parents agree? We talked to two local moms who have children at the Homer Plessy Community School, a 1-year-old charter school with an arts-integrated, Reggio-inspired curriculum. New Orleans newcomer Marcea Pierson chose Plessy for two of her three sons after doing a lot of homework on the city’s local charter environment. When she walked into Plessy, she was impressed not only by its principal, Joan Riley, but also by what she saw.

“She said, ‘This is still a work in progress. This is not perfect. We just started last year. Don’t expect to come here and have perfection. But the stuff that I saw was just really exciting,” Pierson says. “The fact that she had been at Edward Hynes gave me a lot of hope that she would have the academic side. And I could see the arts everywhere when I walked around the school. There was spray painting on the wall, and art projects on the ground.”

Esme Roberson switched her daughter to Plessy after the two went to the school last fall to visit one of her child’s friends.

“When I walked around and saw his classroom they were talking about plants and their hermit crabs’ adventures,” she recalls. “They were very engaged in talking with the teacher about all kinds of things and they looked very excited to be learning. I felt like she hated school already, and so I switched her two weeks into the school year. I liked how much they enjoyed learning.”

An arts-integrated curriculum like the one at Plessy is not so much about what is taught, but the way things are taught. Learning comes from doing. Pierson was struck by that methodology early on.

“They were learning Egypt when we got here, and I was so excited because they said we’re going to mummify fish. So that’s what they did. They mummified fish. They actually put it in the salt, and it took weeks. … Also, in Egypt one of their instruments was like a Y stick, like a dousing stick, with a string across. They put bottle caps on it and they played it. So they made the instruments; they played the instruments. I just think there are all these details about Egypt that they will remember.”

Plessy takes this project-focused approach one step further, using the Reggio Emilia system for inspiration. This Italian educational movement concentrates on individual exploration and discovery.

“Reggio is also very much following the child’s interest,” Pierson explains. “You may come into the class with a lesson plan, but if, say, you are outside and a grasshopper falls in the middle of the group. Instead of shooing that away you would stop and say let’s talk about that. The other thing is that when you walk into a Reggio Emilia classroom you shouldn’t see a lot of things on the wall, A to Z and stuff like that. Because if you’re going to have that, then have the kids make it. Because if it’s already on the walls when you walk in, it’s your grandmother’s wallpaper. You’re never going to notice it. But if you make it yourself and then put it up on the wall, then you’re going to look at that and you’re going to remember it.”

“Having made a lot of mistakes in my life, I see the value of them,” Roberson adds. “I think that letting them loose to explore to fall down and get up is really important learning.”

But do parents worry in this era of Common Core and testing that such a free-flow learning environment will cost their kids future SAT points? Not so much.

“If you’re in public school you’re going to have common core drilled into you no matter where you are,” says Roberson. “They get their Common Core and they work on their test for that, but I think the things that will stick with them are not those kinds of drills.”

Plessy does administer standardized tests to students, and offers tutoring for those who want or need it, but Pierson says she likes the idea of more hands-on learning.

“I think it does amazing things for them. Boys don’t want to sit at a desk and watch somebody talk at them the entire time. At Plessy, when they’re actually using their hands to make something, or using their hands to make a project, it gets them up out of their chairs, it gets them up moving around.”

Still, an arts-integrated education has learning curves for parents, too. Pierson recalls wondering why her son wasn’t bringing home math homework.

“So I talked to the teacher, and I said, Is he supposed to be bringing home homework and he’s just not doing it? And she said, it’s hard when you’re doing project-based stuff to bring a worksheet home, because that’s not really what we’re doing. But I know that it’s being incorporated.”

Neither of these two mothers put their children in Plessy to teach them the arts. While one of Pierson’s sons is artistic, the other is not. “I don’t think that he would have been challenged at a school that wasn’t making him do something out of his comfort zone.”

Still, an artistic environment introduces kids to new things. One of Pierson’s sons recently took up the violin, something she doesn’t think he would have discovered at a more traditional school. And Roberson says that Plessy has made her daughter more creative.

“I think because she’s in Plessy she’s artistic. I wouldn’t say that she has a natural talent for visual art necessarily. But she loves doing it. She was drawing for hours last night. Whether or not she’s any good at it, I think it’s important to be creative.”

Beyond instruction in math or reading, an arts-integrated school teaches children broader life lessons, these parents say.

“The community is really amazing,” Roberson says. “I really think the kids are friends in a way that I don’t think I was. They’re really a good group of friends. And a whole group. I like that a lot.

“And it’s important to make a person who can get along with other people and who knows how to deal with all kinds of people and be an examble to the littler ones. And then there’s also the arts, and how that helps with academics. I think it is the whole thing: Those three things — the arts, the academics and the community – that really do make for a whole child.”

Ultimately, these two mothers think that an arts-oriented school will make their children better adults.

“I want what everybody wants, for my kids to be happy,” Pierson says. “I think that encompasses more than what I was aware of when I was younger. Happiness is not being rich and just sitting around the pool all da.y It’s being challenged, doing work that matters to you, being passionate about something. Then I think you end up being a happy person.”

On Saturday, Plessy joins Morris Jeff Community School in an art auction to benefit both schools. It starts at 3:30 at Café Istanbul, 2372 St. Claude Ave. and it’s free. Dozens of professional works of art, as well as selected student pieces, will be available for sale. After a cocktail hour, John Calhour will emcee a live auction starting at 4:30, with a concurrent silent auction running until 5:45. For more information, click here.

This continuing series about arts and education, a partnership of WWNO and NolaVie, is made possible by a generous grant from the Patrick F. Taylor Foundation.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.