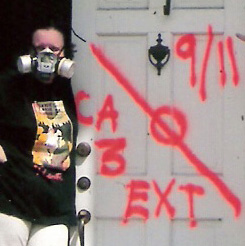

Masks and tattoos in the early days.

I call them my D&D tours. For Death and Destruction. Such was my mindset a decade ago, when I first began showing people the effects of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans.

In the past 10 years I have given dozens of these tours, and they have been a learning experience as much for me as for my guests. Because a two-hour drive through New Orleans, tracking the aftermath of the storm, teaches you like nothing else where the city has been and where it is going. It’s a ground-level, gut-wrenching barometer of damage, recovery and change.

My first D&D tour took place over Thanksgiving 2005, just three months after the storm had pushed water from Lake Pontchartrain into manmade city waterways, where it burrowed into the unfirm foundations of levee walls and flipped away large sections of earth to create catastrophic breaches that flooded 80 percent of the city.

It was a gray November day – weren’t they all gray back then? – and my guest was Quintus Jett, then a professor at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. He had gotten my name from my daughter, a Dartmouth senior, at a campus rally in Hanover for displaced Tulane students — many of whom had spent but a week of their lives in New Orleans. Megan gently suggested that perhaps the (few) Dartmouth students actually from New Orleans should be included, since they, like her, had lost everything to the storm. Wow, said campus organizers. They hadn’t thought about that.

It was the first of many reminders to come that people in the Great Elsewhere didn’t quite think through what had happened down in New Orleans, and what it meant to the people here.

That first tour set the course of the dozens to follow: Metairie Club Gardens to Lakewood South, a jog under I-10 to Lakewood North and then across Veterans into Lakeview and a stop at the first major canal breach at the 17th Street Canal. (That was the one that got my house in East Lakeshore.) Then down Robert E. Lee (if it’s still called that at the time of this writing) to Pratt Street, and the second breach at the London Avenue Canal. Through Gentilly and past UNO, over the Seabrook Bridge and then a turn from Downman onto Morrison Road for a trek through New Orleans east. Up onto I-10 to the 510 exit, past the never-revived Jazzland theme park, getting a bird’s eye view of Mr. Go and the wetlands, and then into St. Bernard. A right turn onto Judge Perez Drive, leading into the Lower Ninth Ward and the breach at the Industrial Canal there.

For two hours, you don’t see any part of New Orleans that wasn’t flooded. You drive past the three major levee breaches, and dozens of neighborhoods that were ruined. You drive past millionaire’s homes, middle-class homes, blue-collar homes. I wanted to show that, contrary to national perception, this storm drew a wide swath through the city – impacting every demographic, every race, every gender, every age, every income level. It was an egalitarian disaster. And that, as much as anything, drew us together as a community.

D&D tour 2006 (Photo: Renee Peck)

On that first tour, there were still cars hanging shakily from tree branches (including the one Anderson Cooper liked to broadcast in front of); houses collapsed on foundations as though a giant hand had swatted them like pesky flies; piles of spiky brown and gray debris beginning to build on neutral grounds and green spaces.

We were still learning things back then.

That magnolia trees are killed by sitting weeks in briny water, but live oaks are not.

That the spray paint used by national guardsmen to mark houses they had searched was indelible, both physically and emotionally.

That water didn’t go over the levees, but under them, and ate away at weak foundations.

That water destruction has three variables: speed, depth and duration. Katrina’s had sent a triple whammy: waters powerful enough to toss a friend’s grand piano upside-down against a wall, deep enough to climb second stories and onto rooflines, and stationary long enough to send tenacious moisture into crawl spaces and behind cabinets.

Even on that first tour, however, I found myself looking ahead – and for that I thank Quintus. “You know,” he mused as we passed block after block after block of empty, ruined homes, “if someone could count and quantify this, it would help to get a handle on the need.” Quintus and his students returned numerous times afterward to do just that: Map the destruction and chart the rebuilding, to document what areas were coming back, and where help was most needed.

In the years that followed, I gave my D&D tour several times a month, to friends, friends of friends, visiting volunteers, journalists, students, strangers. My show-and-tell was a way to educate, to elicit understanding and empathy, to thank people for their interest and help, and, for me, to heal.

Because every time I drove that route, I saw a little less destruction and a little more recovery.

The shattered cars gave way to dead refrigerators, locked and laced with satiric messages. The dead branches and gutted drywall and discarded furniture moved to the curb, then to the neutral ground, and finally to the landfills. Broken windows gave way to boarded ones, then to new panes of glass. Concrete foundations and front steps to nowhere were carted away, to be replaced by weeds and brush, and ultimately freshly mown lots and even new homes.

My D&D tours tracked neighborhood progress, too. From blue tarps to thousands of FEMA trailers in the driveways to construction clutter. Not surprisingly, areas with more means returned more quickly. The beginning part of my tour soon looked much better than the neighborhoods at the end of it. Although even today, no area is completely free of still-vacant lots, or still-blighted properties, or still-shuttered strip malls.

All that debris … (Photo: Renee Peck)

In those early years, my tour guests generally reacted with dismay. Most of them had no idea that the area of destruction was so large – the size of Manhattan – or so devastating. Although a friend from Michigan was not so overwhelmed. As we passed a deserted mall, she said, “This is destruction? It looks just like Detroit.”

The middle tour years were filled with explanations about base flood elevations and the Road Home program. About the way that insurance payouts often went to banks to pay off mortgages rather than homeowners to rebuild. About why so many structures were going up onto stilts (I call them the “never again” crowd). A favorite stop is the house on Pratt Drive built like a boat, with Katrina flood levels etched into a marker in front.

Gradually, tour talks turned from destruction to rebuilding. The Brad Pitt houses went up; Musician’s Village was added to the tour. Massive pumping stations began to appear alongside drainage canals.

I was often asked why I rebuilt my flooded home. Aren’t you afraid of it happening again? Not at all – breach locations determined what areas flooded, and given the amount of concrete now visible along the 17th Street Canal levee, my Katrina house will never flood again. It looks like a space station on Mars there.

Nowadays, I’m rarely asked to give my D&D tour. Unless you know where to look, it’s easy to drive through all parts of New Orleans and miss the lingering vestiges of Katrina. I’m hard-pressed these days to find Katrina tattoos to show visitors.

People are moving on, and looking forward. And that’s a good thing. When I first returned to my ruined house on my ruined street on a dreary September morning in 2005, I remember thinking that it would take a year to rebuild. No, I thought, two. No, maybe five. And then I looked around. Ten, I decided.

And 10 it is. A colleague remarked recently that the 10 years past have been for rebuilding, but that era is over. The 10 years ahead are for just building.

Amen to that. I will hang up my guide credentials with gladness.

Click here for a playlist of favorite This Mold House columns, which I wrote for The Times-Picayune InsideOut section after Katrina.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.