Editor’s note: In a series last fall called Voices from the Classroom: The Arts in Education Reform, NolaVie and cultural partner WWNO public radio teamed up to take a look at how the arts are being used creatively in schools around the city. With the start of a new school year, and education in New Orleans a more vital topic than ever, we are reposting stories from the series. In this installment, Renee Peck looks at an arts-based school that is rooted in the past.

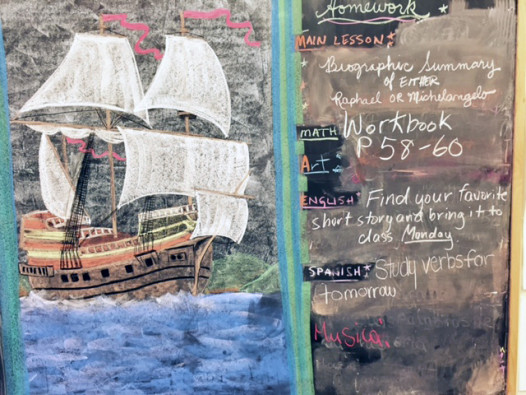

Chalkboard lessons at the Waldorf School in New Orleans (Photo: Renee Peck)

The Waldorf School in New Orleans is located in a renovated bread factory in the Irish Channel. That’s appropriate, because, while other schools have recently been adding arts integration and experiential learning into their educational mix, the Waldorf method has been doing it for nearly a century.

A Waldorf education is designed to teach the whole child, and focuses on the individual. Developed by German philosopher Rudolf Steiner in 1919, this teaching approach was partly a response to the times..

“This was in the wake of World War I and there was profound concern that something like that never happen again in Europe. So there was a lot of soul seeking,” Waldorf board member Margaret Runyon explains. “How do we provide a healing education for the future? Waldorf education was developed in response to this, to integrate the spiritual and physical and emotional and intellectual development of the child.”

At the Waldorf School in New Orleans, parachute silks and gauzy netting are draped across ceilings, while vibrant chalkboard paintings tell stories of adventure and discovery. Silk squares hang on the wall, ready to be pulled down to serve as instant capes or costumes for imaginative play.

Organic shapes, silk drapery, wall murals adorn the Waldorf library. (Photo: Renee Peck)

Shapes tend to be organic and wall colors are chosen to correspond to various ages and developmental stages – first grade gets peach blossom. Here and there, sponge-painted walls or old brick add a three-dimensional quality. You’ll see the usual alphabet or multiplication tables on display, but the eye is more readily drawn to the gaily colored kites flying overhead, or the myriad art supplies being molded by small hands into creative creatures.

Waldorf classes are hands-on and collaborative. Children are encouraged to engage with one another, to create projects together. Their work is their play. But a pivotal aspect of the school is not who attends, but who leads. Runyon says that if she had to give a one-word answer to what makes Waldorf unique, it would be the teacher.

“Young children learn imitatively, but they also seek authority, a loving authority. So who the teacher is in front of these children, what does that teacher bring from inside? Not just content-wise, but who are they? Is that teacher someone who is engaged and interested in the world and looking for solutions and creative and artistic and is this someone who has joy in life? That’s what’s conveyed to the children on a very deep level.”

“There’s no Christmas goose stuffing of information,” says fifth- and sixth-grade Waldorf teacher Rebecca Nelson, fresh from a lesson on the Roman republic. “Our biggest challenge and responsibility is to bring each kid along at his or her own level. I feel like I know these children well, and my expectations are tailored to each child. What I might praise to the skies to one child I might give back to another to do again.”

Nelson earned a master’s degree in Waldorf education after volunteering as an assistant teacher at Waldorf. “I fell in love with it,” she says. “It was incredible what they learned and what I saw.”

Like all Waldorf lead teachers, she spends time with the families of each of her students, in their home environments. “It connects me to the child, and allows me to be a better teacher.”

Teaching is hands-on. (Photo: waldorfnola.org)

Waldorf parent Ginny Kaczmarck chose the Waldorf School for her two sons after hearing a talk by Waldorf educator Torin Finser.

“He spoke a great deal about teachers, and this concept of school being a place not only to learn ABCs, but also how to be citizens of the world. That really spoke to my husband and me. We really wanted to be in that kind of community with other parents who value teaching their child to be responsible citizens, to be strong individuals who can speak their minds, who can think for themselves and also people who can collaborate with others in the world to make things better.”

Others seem to agree. Waldorf education is growing exponentially across the globe, even in places like China that have traditionally favored a more structured education. The New Orleans school, started in 2000, has 91 students this year, and is expecting 104 students in the fall. Lead teachers generally stay with the same students all the way from first through eighth grade. Some, like Nelson, take classes through upper or lower grades, and there are teachers for music and other independent subjects.

You won’t see standardized tests or laptops in a Waldorf classroom.

“This goes back to the philosophy of honoring the individual,” Runyon says. “Evaluations are done through written reports and there are definitely goals, developmental goals that are established and striven for. But standardized testing is really a very not Waldorf thing.”

As a parent, Kaczmareck likes the focus on active learning rather than technology tools.

“In eighth grade, when it’s time to beginning to learn about computers, what they do is take a computer apart to see how it is built, then they learn how to put one together, how software developed. So now they’re understanding it from the inside out, not just as a flat thing they use.”

Student artwork in the Waldorf office (Photo: Renee Peck)

Waldorf teaching encompasses a sense of place, too.

“We’re a New Orleans school,” says Kaczmarek. “So New Orleans is brought into the education. The children celebrate New Orleans culture, New Orleans music. It’s global in this concept of children needing to learn how to work together, work across differences, that’s universal, but there’s also this sense of pride in who you are as an individual and where you come from and that’s a huge aspect of the community, too.”

The Waldorf system may be anchored in the past, but proponents believe that experiential learning – and letting kids be kids – is crucial in an ever-more competitive contemporary world.

“I think that Waldorf really seeks to provide an antidote to that,” Runyon says. “I think if you look again at the natural world, we’ve been kind of brainwashed with this kind of Darwinian competition kind of thing. We’ve got to flip the script on this a little bit. We have to understand that there is a different way to work, to honor differences, to honor each other, to work together. It’s not just about holding hands and singing kumbaya. It’s about the survival of the planet.”

This continuing series about arts and education, a partnership of WWNO and NolaVie, is made possible by a generous grant from the Patrick F. Taylor Foundation.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.