Last year, the arts and education movement in New Orleans got a big boost when the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts named the city one of 17 target sites for its Any Given Child program. This initiative helps communities develop a long-range plan for expanding arts education in local k-8 schools. Any Given Child cities are seeing more full-time arts instruction, a far greater number of students being exposed to the arts, more performing arts groups going to schools and more funding for arts education.

The core governance team for Any Given Child in New Orleans includes the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation, the City of New Orleans, the Office of Cultural Economy, NOCCA, the Cowan Institute and Artist Corps and KIDsmART. Echo Olander, director of KIDsmART, talks to NolaVie about what they’ve done and where they are in the process.

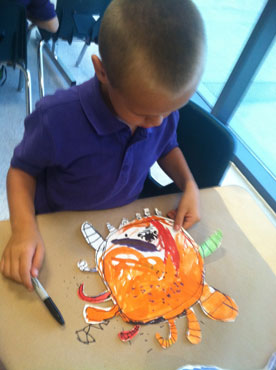

‘The creation of an art form is a demonstration of knowledge.’ (Photo: KIDsmART.org)

What have you done in the plan’s first year?

The Any Given Child process was a planning process, and we worked with a group of people who represented the education arts, business, philanthropy and community communities who met monthly. Then we had a number of stakeholder meetings with arts institutions, with schools, with teaching artists and parents and got feedback from a lot of different people. We had almost 1200 participants that worked with us on this process and we conducted 29 meetings to hear what people were interested in having, what some of the issues were, and what the solutions might be and to pull that into a cohesive plan.

What are the goals?

The plan for Any Given Child – which is a working title – is to create access and equity to an education that includes the arts. There are several different ways the arts can happen in schools. You can have arts instruction, which is teaching a child to dance or paint or sing uniquely. You can have arts integration, where there’s a balance of focus with the instruction on both the regular content area, which might be science, math, social studies, English language arts, and the art form, which could be theater, dance music, visual arts. Then there’s also arts enhancement, which might be having a performance come or learning the ABCs with a song, where you’re using the art form but you’re not necessarily studying the art form.

No one thing is better than another. All of these things are good. The intent is to have more arts and have the arts be excellent for every child, so not just the people who come to really strong schools or who are in private schools get this instruction.

Why is arts education important?

There are a lot of reasons why the arts are important. One of them is around engagement and getting children to really engage with the content area and to really enjoy learning. The arts are a great way of exposing whether students know something. The creation of an art form is actually a demonstration of knowledge, which is a really interesting way for teachers to evaluate whether students understand what they are doing. Art connects people and allows children to understand their environment a lot better.

Most people are now understanding test scores are a really limited way of understanding student success, and the arts give a lot of variety in ways of understanding whether students are connecting, understanding, communicating and excelling.

You’ve spent the last year talking to people. What did you learn?

We did a data search and what came back from the data was the absolute understanding that there’s not a lot of consistency with terminology and with what people are calling different things. … The biggest thing we learned out of it is that it’s a highly decentralized system of schools and there’s a real need for coordination of information and data around the arts and what’s being offered, who is offering them and where they’re offering them and at what levels they’re offering them. So the need for a centralized information source was one of the biggest takeaways from the planning process.

In June you came up with a draft of goals.

We came up with a plan for how to get more arts into the schools. … There was a real demand from the community in aligning the language around what was excellence in education and how would you know if a school was excellent. So even principals and school leaders said, we want to be an arts excellent school, but what does that mean? So one of the things that we’ll be doing is creating a rubric that can demonstrate both to parents, to cultural institutions, to all of the community, to schools, where a school might be on the spectrum of low arts work and high arts work.

Can you expound a bit on what an arts excellent school might look like?

When we’re looking at what an arts excellent school is, it would include a lot of different things. It would include instruction in multiple art forms. It would include that instruction being taught by certified arts specialists. It would include connections with community and cultural organizations. It would include exhibition possibilities for the students. It would include support for teachers. It’s a whole list of different things that a school could do to move toward that spectrum.

One of the things we really want to strive for is sequential learning in the arts, so that knowledge builds upon knowledge. Just as you would never drop a child into calculus first, you have to build their knowledge about math as they go, sequential learning in the arts is a real indicia of an exemplary school. So they learn the notes, they learn harmony, they learn collaborative work with other, they finally compose. That’s one example. We would really like to see the students come into a school system and get arts throughout the whole school and that knowledge builds on each other. That knowledge becomes really deep and really true.

So what are the next steps?

In this first year post-planning, one of the things we’ll be doing is creating some common definitions for arts education, so that as a community we are all looking at the same thing. We also will be starting some work on mapping something in a digital way. We’re going to work with Artist Corps, who’s been doing a lot of work with music and they’ve starting mapping really deeply what’s happening in the music field, and we’re going to use that to pilot some work and create a website that we can expand to all the other forms as we go on.

There will be different access spaces, so if you’re a school you can come to a certain part that’s not open to everybody else, likewise for arts organizations. But parents and the general public will have access to a lot of information about what is available where. We’ve been looking at some of the amazing models that are coming out of Los Angeles and Chicago that are doing some of this work to try to help people understand where the arts are happening and how they are happening at those schools.

We’ll also be doing some professional development. We’ll have school visits with presenters from the Kennedy Center. We’ll do workshops for teachers. We’ll have workshops for arts organizations and we’ll be doing some training with teaching artists.

This is a community-focused effort. What has the reception been from schools and the art community?

We were so joyful that there was so much excitement about this work. … There was so much enthusiasm. I think there is a real hunger. I think people in New Orleans understand that culture and the arts are critical for our survival as a cultural city. We have to have that in our school system. We have to feed that area of our souls in our community. And if we don’t do that, we run the risk of having it go away. I think people really understand that, and the work is really around creating these pathways so that people can do that — so that different arts organizations can connect with schools, so that schools can connect with community and it can be a whole collaborative space.

A group of different organizations over the past few years have been doing training with teaching artists. So the CAC, Ashe, Ogden, NOMA, have all come together to put some things together so that we can build capacity of our artists working in this community to do excellence.

How many schools have indicated a desire to participate?

The Kennedy Center worked with K through 8 schools and we had 32 schools that signed on to do the original work. We see this as how you throw a stone in the water and it ripples out. There will be expanding circles of impact. We’ll start some focus on those 32 schools but it’s not intended to be exclusive at all. It’s inclusive more than anything else. … Right now it’s just Orleans Parish. It’s a lot to get your arms around Orleans Parish, so we’ll start with that.

How do you sustain a program like this?

Sustaining is a big part of it. … I actually truthfully feel that as the arts get more comprehensive and the quality of them increases, the community will require it and the sustainability will be around community desire and community need. There are a lot of things that will go into supporting that with the advocacy, communication and investment sides.

How is New Orleans doing compared to other communities?

I was surprised at how much there was. KIDsmART works with 11 schools and I was pretty familiar with those schools, but the richness that existed in a number of schools was a little surprising.

For more about Any Given Child, go to the KIDsmART website, where you can sign up for email notices about the program’s ongoing efforts.

This continuing series about arts and education, a partnership of WWNO and NolaVie, is made possible by a generous grant from the Patrick F. Taylor Foundation.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.