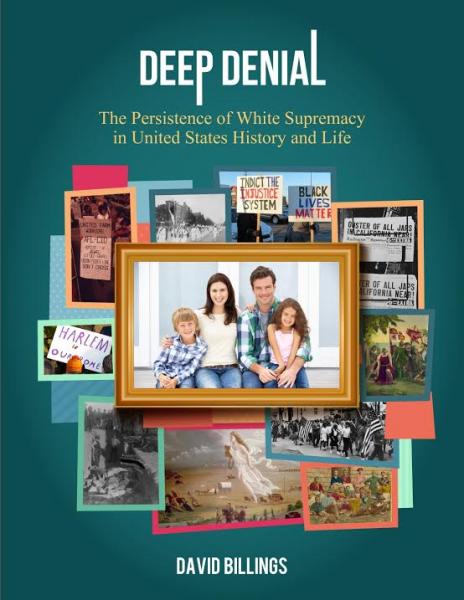

Deep Denial: The Persistence of White Supremacy in United States History and Life, by David Billings

Deep Denial: The Persistence of White Supremacy in United States History and Life, by David Billings

“Race is the Rubicon we have never crossed in this country.”

That’s David Billings’s thesis in his provocative new history/memoir. It documents the 400-year racialization of the United States and how people of European descent came to be called “white.” Billings, a leader of anti-racist workshops, an historian, organizer and ordained United Methodist minister, focuses primarily on the deeply embedded notion of white supremacy. He tells us why, despite the Civil Rights Movement and an African-American president, we remain, in his words, “a nation hard-wired by race.”

A master storyteller, Billings starts each chapter with a disarming and intimate vignette from his personal life, beginning with his white, working-class boyhood in Mississippi and Arkansas. He then situates these telling stories in a broader historical context that will be new and disturbing to many readers.

Part I covers the origins and evolution of white supremacy from 17th century Virginia through World War II. Part II focuses on the Civil Rights Movement, how it emerged in the post-WWII era, and why it subsequently devolved from a vibrant community-led, issue-based movement into today’s bureaucratic, government-sponsored, needs-based, nonprofit industry. An epilogue discusses strategies for dismantling white supremacy and “undoing” racism in America.

Billings argues that white supremacy has a well-documented history. It profoundly shapes our laws as well as our collective psyche like a narcotic coursing through the veins of all white people, including himself. And yet it is not studied, not discussed, and virtually unknown to most Americans. Why?

Paradox abounds. Billings notes, “Whiteness is everywhere. People of color can’t get away from it while whites are trained not to see it at all.” White people were “set up” long ago, he reasons, so that their relationships and values, and therefore institutions, have been cultivated within the framework of a race-constructed nation. The set-up started with the founding of the nation through law, religion, and pseudo-science – including eugenics and early strains of anthropology. In order to justify the twin pillars of American white wealth – free land from Indian nations and free labor from enslaved Africans – white supremacy was enshrined as God’s will and evolution’s mandate. We called it Manifest Destiny and survival of the fittest. Billings’ careful research documents how, when, and by whom.

White, then, for Billings, is a political, not an ethnic designation. It signifies one’s relationship to sanctioned state power. But it goes beyond being a philosophical justification. It is also an organizing (or rather disorganizing) strategy. Billings points out that a “color-coded racial pecking order which shifted as Jews and Italians became assimilated insured there would never be class solidarity.” Being white, in a race-constructed nation, trumps (if you’ll pardon the pun) even economic self-interest.

The social contract embeds promises to white people including systems and institutions that work for them. Whites have options and freedom of movement. One example is the Federal Housing Authority that from 1934-1962 provided a $120 billion head start on white home ownership and, with it, white equity and the ability to pass that on from one generation to the next. As a result of such structural advantages, whites internalize these advantages as superiority.

Internalized Racial Superiority is a “multi-generational process of racial entitlement and white privilege that gives whites a sense of special place in the US,” Billings writes. Individualism is at its heart. Individualism allows whites “the privilege of denial of intent when it comes to collective white advantage.” People insist: I’m not racist. I don’t mean harm to anyone. I’ve worked hard for what I have.

Billings makes a strong case for the cost of that denial to white people. Never mind that whites holding themselves above most of humanity is lonely and false and has to be constantly defended. Whites also live in fear, which is politically exploited, with the vocabulary hardly even changing from generation to generation. In general (I can already feel whites bristling about being generalized), whites believe that blacks are violence-prone. Whites try not to say that in public, however. Given the history, I think that generalization would make more sense reversed.

Moreover, in this context, whites fear retribution from blacks for what whites have done to them. There is a fear that black power will come at the expense of white privilege. And yet there are towering examples to the contrary. Nelson Mandela, freed from prison after 27 years, invited his former oppressors to stay and help build a new nation in which racism was outlawed. After the 2015 murders of members of Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church, fellow parishioners refused to demand or even tolerate vengeance.

Billings also meticulously documents the resistance to white supremacy throughout our history. He describes the Civil Rights Movement in vivid detail. The leadership of a movement seeking to break the shackles of white supremacy has to come from people of color. In the Civil Rights Movement, for the first time in our country’s history, whites took a back seat to the mobilized strength of marginalized people. It constituted the biggest challenge to the racial status quo since the Civil War.

But ironically, its victories held the seeds of its demise. The strategies that had gained people of color access to institutions had to be put aside. Once in, if you wanted to stay in, you had to conform to the institution’s rules and its ways of being, one of which was to put racism at the end of a long list of “isms.” Celebrate the Movement on its high Holy Days, but acknowledge that militant mobilization is something whose time has passed. Notes Billings, “The Movement that had changed history would lose its vibrancy before it achieved its vision.”

The Great Society under Lyndon Johnson established the Economic Opportunity Act in 1964. That put in place the underpinnings of an inclusive social contract “with maximum feasible participation of the poor” as an organizing principle. Head Start, VISTA, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Humanities all had their beginnings during the Great Society. But as soon as federal money began flowing through nonprofits, the poor were more or less relegated to “units of service.”

Michelle Alexander in her 2013 book The New Jim Crow says, “We have not ended racial caste in America; we have merely redesigned it.” The structural inequities remain. The very language of racism continues to morph. The myth of white supremacy has been replaced by the myth of colorblindness. Whites spent the better part of 400 years justifying white supremacy in law, science, and religion. The minute whites begin to realize that there is no justification for white supremacy, whites change the subject, claim race neutrality, and think they can move on without acknowledging, much less cleaning up, the mess that has been made.

Billings’ book gave me a new insight: It doesn’t make sense to blame working-class whites for their anger and resentment. They have had to deal with the real-life consequences of integrating systems that were never designed to serve everybody. Whites, more affluent progressives, send their kids to private schools, protect the value of their real estate, and keep their jobs. Who am I to judge? It’s my internalized superiority that prompts me to cast that stone from my glass house, the stone that says “you are a racist.” I wouldn’t be living in that fancy glass house without the benefits that historical racism brought me.

Our poor white brothers and sisters aren’t trash – disposable. They’ve been set up by the politically constructed lie of race in which we are all complicit. And we’ll all have to work together across race and class lines if we ever want to undo racism. Billings thinks we can. He maintains that racism cannot last. In fact it is already dying. Through anti-racist community organizing rooted in an accurate understanding of history, in culture, and in spirituality, white people can reclaim their full humanity by “destroying the beast that dehumanized us in the first place,” a beast that through Billings’ ground-breaking book is beginning to take form and shape.

May we now summon the courage to have eyes to see and ears that hear. That’s what it takes to first fight our own denial and then fight the beast itself.

Orissa Arend (Photo: Jim Belfon)

Orissa Arend is a mediator and psychotherapist and author of Showdown in Desire: The Black Panthers Take a Stand in New Orleans. She is also a member of the Episcopal Bishop’s Commission on Racial Reconciliation.

This review also was published in the Louisiana Tribune newspaper.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.