NOLA native King Mallory

If I’d checked King Mallory’s resume (Aspen Institute, Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, U.S. Department of State, etc.), I wouldn’t have had the audacity to ask for an interview. I knew I was out of my depth when I met him at a coffee shop and found him reading a book on game theory that would be applied to nuclear negotiations with North Korea and Iran. But he was great and talked to me as if I knew what he was talking about.

King had just come off a year of advising the Ohio Governor John Kasich as National Security Policy Advisor to his presidential campaign. A Kasich top aide kept calling, but King was too polite to take the call during our interview; well, until the third call. As well as being polite, he is a Republican and the son of a Queen of Rex. Though they may be his roots, he has traveled far.

I was leaving for my annual week in New Mexico — all-art, all day, with wonderful women, in divine Taos. So I told King I wouldn’t get this story done until I returned. That was more than a month ago. Besides the devil that took up residence in my back and neck, I blew our interview in a brand new way. The minute I got settled in my seat on the flight to Albuquerque, I started transcribing our interview, starting and stopping to write longhand, rewinding to get the words right. Suddenly, the engines started and the plane lurched forward, sending my fingers over my little digital recorder in just the right pattern to totally erase the two-hour interview with King. The plane really did eat my homework. It was a 6:30 a.m. flight; too tired to panic, I just started writing.

King’s father served in the Pacific Fleet; mother and son joined him in San Francisco. Parents divorced and mom married a German man, so at 6 years old King was dropped into a public school in Berlin, speaking not an iota of German. (It really irritated his German teacher, whose country had just lost a war to the Americans, that little King could quickly outdo his native German-speaking classmates in grammar.)

Fast forward to college at Middlebury, where he studied Russian and Arabic (clearly language is one of his strengths). After working for the Rand Corporation think tank in California, he was on to Moscow as CEO of Credit Suisse Investment Funds, where he found himself a French wife for a time. After Russia, he headed home to the U.S Department of State for five years, then back to Berlin, where he was asked to untangle the mess the German branch of the Aspen Institute was in at the time.

Now he finds himself in NOLA, happily taking it easy where he began. Likely he’ll move on to reckon with problems like nuclear proliferation, never-ending muddles in the Middle East or the conundrum in North Korea. But for today, he was willing to take on our local problems.

On venture capital tax credits:

King says, “The Louisiana venture capital tax credits are, to my knowledge, 20 percent higher than the median offered to venture capitalists in the rest of the country. They are so lucrative, in fact, that there is a secondary market in them.”

But with venture capital, “one has to ask where are the ‘success stories’ from the venture incubators in town? If these incubators are creating such a positive long-term impact on the local economy, then show me: Where are the numbers of people employed? Where are the successful IPOs of New Orleans startups? Where are the numbers for additional tax revenues to the city? They are not there, or at least not very visible.”

King gave me an example of what he says is “socializing the costs, but privatizing the profits.” If venture capitalists invest in, for example, 10 Louisiana projects, they get millions of tax dollars as subsidies. Say two out of the 10 succeed. There is no mechanism for Louisiana taxpayers to participate in those successful companies, yet they have backed all 10 of the projects. The winners are the millionaires who had money to bet on the ventures and who got tax credits as well as tax reductions.

“In both cases, the tax credits are the way the top 1 percent seek rents from the rest of us.”

King thinks one solution would be for the National Governor’s Association to set the going rates nationally for all tax credits, for both Hollywood and venture capitalists, to stop the free fall of states beggaring one another for the benefit of the top 1percent.

On running for office:

I asked King why he didn’t go into local politics and he laughed. “I talk funny.”

More seriously, he said, “I love this city, so much opportunity here, a lot of talented people here because they like the lifestyle. It’s just a question of tapping into that. I don’t know if I have thick enough skin for politics. They’re going to call you everything under the sun. Seeing the stuff the media threw at squeaky clean Governor Kasich, the distortions, I’d have to think long and hard before putting my family through that. When I entertained the idea of getting into politics my mother said to me ‘Don’t do it! Don’t do it!’.You’re just going to get down in the mud with the pigs, and the pigs are going to be enjoying themselves.”

On thinking big, really big:

On thinking big, really big:

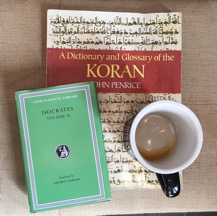

The project King is working on now is staggering: an English language study guide of the Quran. His thinking is, how can we talk to, understand, negotiate with states and ideological movements that base their politics on this ancient book if we have no understanding of it?

His takeaway from five years working at the State Department: “I discovered two things: 80 percent of the people working on the Middle East problems didn’t speak Arabic, and of the 20 percent who did, only 20 percent of them had a working knowledge of the Quran. So how could they possibly understand the culture?”

Though not an adherent of this ideology, King feels that, as he sees it, it’s one world and we all have to play in it.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.