Author’s Note: Over the years, I’ve done all kinds of crazy stunts to get kids (and adults) fired up about learning. From dressing up as a superhero named Geography Man, to conducting archeological digs in garbage dumps, they were all well-intended, though occasionally ill-conceived. While most of my lesson and project plans worked out, a few did crash and burn. I figured I could always justify the failures, as long as there was a connection, albeit flimsy, to the curriculum. I usually could – but not always…

Making Sausage

Sausage (notice the picture of Ms. Savoie) (Photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

I once took a group of 7th grade girls on a trek across Louisiana. We were only gone for four days and three nights, but it took years off my life!

One of the many stops along the way was Savoie’s Cajun Products in Opelousas. The company specialized in making smoked sausage, andouille and boudin.

I chose Savoie’s because the owner was a woman. I thought she would be a good role model for my kids. It was also a great example of a successful, homegrown business. And besides, what’s more Louisiana than spicy meat products?

Ms. Savoie was pumped up for us like a Ball Park Frank. “We don’t get many school groups,” she admitted. “Matter of fact, y’all might just be the first!”

As we entered the factory, I quickly discovered why.

The building looked like the prop room from a Wes Craven movie set. There were freezers and smoke rooms filled with hanging, flayed animal cadavers, huge contraptions for grinding up meat and bone, and massive tubs filled with pulverized flesh. The floor was tinted red from blood and the air smelled like sanitized death.

I met a woman who had spent her entire life, eight hours a day, five days a week, inspecting miles and miles of sheep intestines for tears and other defects; and there was a man carefully patrolling the floor, scooping up and “recycling” spilt viscera. The owner proudly pointed out, “We don’t waste anything here. It’s a very efficient operation.”

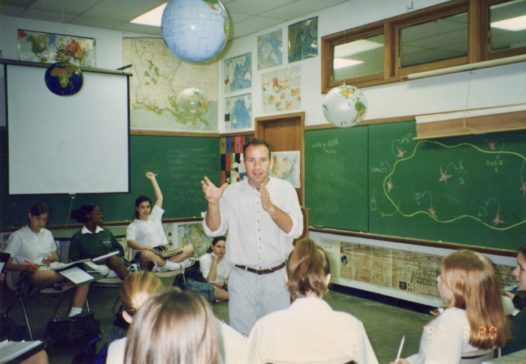

Folwell and class talking History (Photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

The operation was also efficient at taking out kids. Within minutes, my squeamish middle schoolers began to drop like bald cypress needles in winter. High-pitched shrieks were accompanied by a chorus of, “Like, Oh – My – God!”

Several girls bolted for the bathroom; a few didn’t make it. The tour was like an accelerated and rather gross version of the reality TV show, Survivor. I extinguished one Cajun tiki torch after another.

At the end of the tour, the few students who remained were offered a smorgasbord of samples. Needless to say, there weren’t many takers.

When I got back to school, the principal and I were bombarded by calls from irate parents. They complained that their kids had been permanently traumatized by the field trip. “My daughter converted to vegetarianism,” cried one parent!

“What could kids possibly learn by visiting a sausage factory?!” barked another.

“Well,” I replied, “the USDA does recommend that our kids eat more vegetables. And, we definitely learned that the adage about laws and sausage is true: you really don’t want to see either one being made!”

“You Could Have Put an Eye Out!”

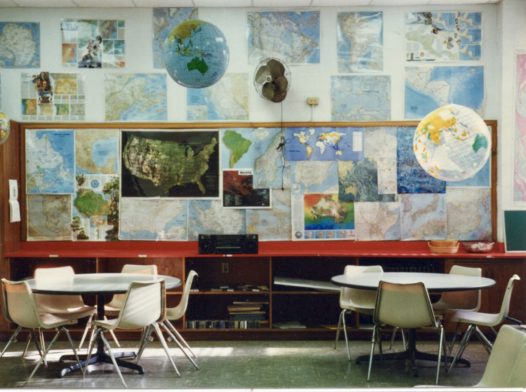

My “cool” classroom (Photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

I once did a unit on ancient weapons. My class and I discussed the Claw of Archimedes, Greek Fire and the Trojan Horse, boomerangs, bows and bolas. We made bamboo spears with Play-Doh points and hurled them across the yard using a makeshift atlatl; and, armed with Styrofoam swords and cardboard shields, we reenacted famous battles like Kadesh, Thermopylae, and Salamis.

I also brought in an authentic blowgun from the Amazon. I had picked it up in Ecuador where I had served as a Peace Corps volunteer years before. I had long since lost the darts though, so I had to improvise by using pushpins and laundry lint. I didn’t have any poison dart frogs either, so I ceremoniously dipped the points in Elmer’s glue.

For my demonstration, I put a dartboard on the door and huddled with my class on the other side of the room. As I prepared to fire, the kids, of course, yelled a line from Gary Larson’s The Far Side: “Blow Mr. Dunbar, don’t suck!”

I took in a deep breath, put the gun in my mouth, and exhaled as hard as I could. As the projectile exited the long barrel, the door to my room suddenly cracked open, and my principal’s head popped in. The kids screamed as the dart grazed her nose, ricocheted off the door and stuck in the jacket lapel of another adult.

Apparently, my principal was giving a tour of the school to prospective parents and board members. She wanted to show off my room. It was covered from floor to ceiling with maps and globes, it had classroom pets and plants, and there was a sandbox for staging archeological digs. It was pretty cool, I have to admit.

As the audience for my blowgun demonstration stood silently with gaping mouths, my principal said in a stern, though surprisingly calm voice, “Mr. Dunbar, sorry for the interruption. Could you please see me in my office after school?”

In her office, I pleaded my case, citing World History standards, research in support of experiential learning, the concept of “appropriate technology,” and the classic book by Dr. Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel.

“I don’t particularly care Mr. Dunbar,” she said. “You could have put an eye out!”

The Pearl River Tea Party

Paddling into the Honey Island Swamp (Photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

I took a group of eighth grade girls on a field trip to the Honey Island Swamp. A friend of mine, Mr. Denny, had built two large voyageur canoes. Each one could carry as many as fifteen people. We loaded up the boats and headed into the swamp.

On the way back, we had to paddle upstream. The current in the Pearl River was strong; and Mr. Denny and I had to do the bulk of the work, since most of the girls were not accustomed to non-motorized vehicles. It was hot and I was thirsty. I yelled to Mr. Denny, “Ya got anything to drink?”

“Sweet tea,” he replied.

“Could I have a swig?” I called back.

“Sure,” he said. Mr. Denny reached into a waterproof duffle bag, pulled out a large plastic jug, and hurled it like a shot-put in my direction. With my paddle in one hand, I caught the jug with the other. I could tell my students were impressed.

I gulped down some lukewarm tea, and prepared to toss the container back. It seemed like a simple task, throwing a plastic jug a few yards. But, in reality, it wasn’t. It was like an SAT question with lots of variables. I had to factor in things like current speed and wind velocity, the sporadic movement of kids and paddles, and the constraints of throwing something from a seated position.

As it turns out, I missed the question and overshot my target. The heavy jug sailed over the canoe, clipping a girl on the shoulder, and landed in the water like an errant cannonball. The startled passengers all jostled in their seats, causing one poor student to tumble awkwardly overboard.

Folwell with his kids (Photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

In that brief moment between the first and second splash, I saw my entire career in education, albeit brief, flash before my eyes.

After the short, nostalgic reel, I quickly turned the boat around, raced after the flailing child, and fished her out of the river. “It’s a good thing I required them to wear life jackets,” I thought.

On the ride back to school, the girls excitedly jabbered on about the incident, while I desperately cobbled together my feeble “curriculum” defense. It included references to the Boston Tea Party and Washington crossing the Delaware, research in support of tough, character building exercises and, of course, the pedagogy of learning by getting your feet – and other body parts – wet.

As I made my way down the hallway toward the principal’s office, I could have sworn I heard an announcement over the intercom: “Dead man walking!”

I felt like Sir Thomas More on his way to meet Henry VIII for the last time, only I was no Man for All Seasons! I was just a humble middle school history teacher (and an amateur swamp tour guide) whose lesson plans had gone terribly awry…

Folwell Dunbar is an educator, artist and former classroom teacher. He once considered a career in law. He can be reached at fldunbar@icloud.com

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.