Janet Hays (Photos provided by: Janet Hays)

A few months ago I met Jefferson, a Nola native who was living in a tent camp on Claiborne Avenue’s right shoulder. We chatted about the two hospitals that were in view: to the north, University Medical Center; to the south, Charity Hospital. Turning south, Jefferson studied the eyesore that loomed above a fire station and Handsome Willy’s Bar. “I was born in Charity,” he said. “They’re cleaning it up right now. I don’t know what they’re gonna do with it.”

The rest of the city is wondering, too. For over two hundred and fifty years—since 1736—Charity was a public institution that cared for the neediest parts of the Orleans Parish population. Everything changed in August 2005, when Katrina flooded the basement of the 2,600-bed facility. Critics claim that LSU, sensing an opportunity to profit from Katrina’s devastation, wanted to keep an outdated hospital closed in order to open a new one with federal and state funding. The next decade was filled with conflict: between LSU and FEMA, between public and private health care institutions, between shrewd developers and community leaders. All the while, Big Charity sat unused on Tulane Avenue, a shabby symbol of disappointment to many New Orleans residents—especially to the poor, largely African-American community that the hospital served.

Janet Hays, a community activist and mental health advocate, submitted a 2015 proposal to restore Charity as a “one stop shop” for mental health care and research. “We are at a critical juncture in New Orleans,” she wrote. “The fate of people afflicted with mental illness rests largely on whether or not we as a society choose to continue to incarcerate sick people under the Department of Corrections, or rather, create alternative facilities where patients can be cared for in a local hospital environment close to their families and community.”

I met Janet last month at the the Sneaky Pickle, where we discussed life in New Orleans, the rise and fall (and rise?) of Charity Hospital, and mental health care in the city.

Janet Hays: I came here as a recording engineer in 2000. I was really drawn to the music and the culture. I never anticipated doing the work that I’m doing now.

Ben Saxton: Where are you from originally?

I’m from Alberta, Canada. I grew up in a family of politicians, so I’ve always had an interest in politics, issues of injustice, and how to make our communities better. Even in the music industry, I was concerned with how the industry discriminates against independent artists.

That’s what I did until Katrina happened. I had come to New Orleans on a work visa that expired in 2005, and for a while I became undocumented. I was stuck in Memphis and knew that, if I left the country, I would have to stay out for two years—under the Bush administration that increased to ten years—which was emotionally traumatic for me. At the same time, my house was under water, my city was under water, people were suffering, and the last thing I was capable of hearing was “you can’t come back here,” because New Orleans has become my home. I’m married to the city. No kids, by the way. At the time, no husband. I came back in November 2006 and eventually I did get married, so now I’m a permanent resident. And my priorities changed from recording engineering to recovery.

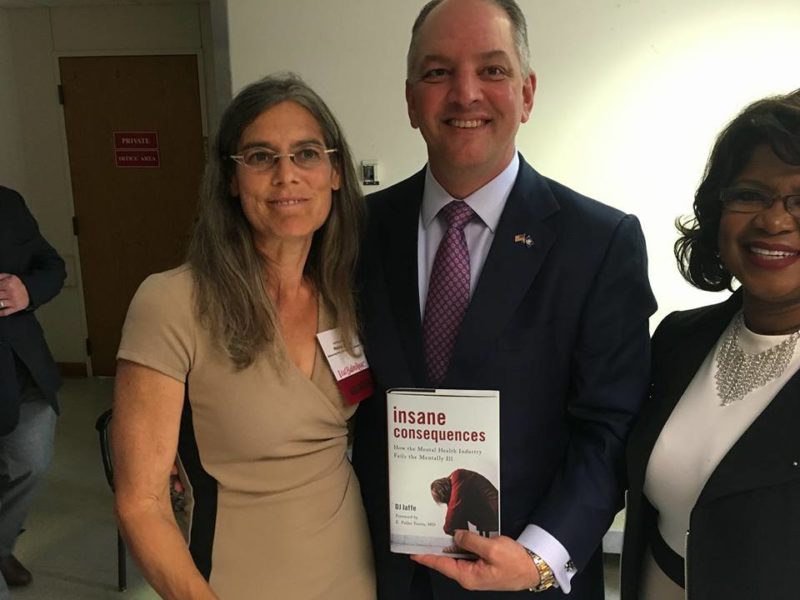

Janet Hays, Governor John Bell Edwards, and Alma C. Stewart (Photos provided by: Janet Hays)

Did that happen because of your involvement with Charity?

It happened because of my involvement with the cultural community. At first I started doing outreach because I knew a lot of people. So often they’d say, “I’m a Charity Hospital baby.” It became a refrain. It was a mark of pride. And people were dying, because Charity wasn’t there. People with mental illness were being incarcerated, because it wasn’t there. When Charity closed, we lost 128 long-term inpatient psych beds and fifty crisis intervention beds overnight. The police were coming to us and saying, “you need to get this hospital open. We don’t know what to do.”

At first our advocacy group wanted to reopen Charity. Then it wanted LSU to put the new hospital inside the shell of the old hospital. The Foundation for Louisiana even hired an architect to show that they could retrofit the hospital inside the shell of Charity, which would avoid the demolition of an entire neighborhood. But the decision had been made. Even before Katrina, LSU had wanted a new hospital. To me, it was unnecessary. Charity wasn’t the greatest. It was a system that needed improving. But they really threw out the baby with the bathwater.

Where are we now, if you think about mental health care before and right after Katrina?

We have an epidemic of people with mental illness. We’ve got a crisis. In 2015, I created Healing Minds Nola in order to submit a proposal to Bobby Jindal, who’d put out an RFI [request for information] to sell the building. That was Jindal’s thing: he was famous for selling off public assets to his cronies. So we—actually, it wasn’t we, it was me at this point—I really wanted Charity to be reused for public use. We’ve got a one-million square foot abandoned building, eight ancillary buildings, and an epidemic of mental illness. Even if we don’t use Charity for a mental health facility—I plan to resubmit the proposal in the future—we still need one somewhere. Two of the biggest barriers to mental illness are transportation and housing, and a one-stop shop provides that. When you don’t have transportation barriers, people are much more likely to get care.

Do any current models exist around the country?

San Antonio’s Restoration Center is often seen as a successful model.

How likely do you think that’ll be in New Orleans? I know there’s been discussion about a mental health jail expansion plan, which is one alternative to a standalone facility.

I think it’s likely. The problem with a mental health jail is that you’ll spend millions of dollars for beds and services, but when people are discharged to the community, they’ll need a place with the exact same services and programs. So you’d have to build the same thing twice. Building a mental health jail also incentivizes incarcerating people with mental illness. It’s sending a message to residents that, if you have a mental illness, you have to go to jail to get help. What kind of a message is that?

In the last decade you’ve delved into health care, politics, the criminal justice system, real estate, development, and more. What have your experiences taught you about New Orleans?

Well…that’s a good question. It’s a tough city. It requires a lot of endurance and fortitude, and New Orleanians are experts at surviving. The city is also very siloed. The areas of industry that you mention don’t communicate with one another, and that’s a big problem. Too many chiefs, not enough Indians. If you could get those sectors to work together we could be moving a lot faster and finding better outcomes for people. Why isn’t the Corrections Department working with the Health Department? Why aren’t they in the same room together? I don’t see any crossover at all.

Because you’re the person hopping into these different meetings.

Yeah. Honestly, I’m the only person who sees the points of intersection. It used to be a running joke: If I’m not at the meeting, then the public isn’t there. I’ve become “the public.” And I can’t be the only one. The struggle for justice is so old that a lot of people have dropped out. They’ve found their happiness in their community. And while I’m out fighting Goliath, the rest of the city is at a barbecue. I used to do that. I would do it today, if I had time.

How’s your own endurance and capacity for hope holding up?

Where there’s help, there’s hope. I definitely have good days and bad days.

For people who are interested in getting connected, what would you recommend?

Well, first of all, politicians listen to the loudest voices. Building capacity for Healing Minds Nola is the most important thing that needs to happen. The problem is that we don’t have enough bodies willing to come into the room. That’s because consumers are incarcerated, homeless, or dead, and families are dealing with a mental health crisis and trying to make ends meet. They don’t have time to lobby.

What I really want to do is a story sharing campaign, specific to Louisiana, for people who have had a tragedy due to a mental health crisis. I’d love it if people would share their story in two paragraphs or less, and send it to healingmindsnola@gmail.com. That’s probably the best thing that could happen.

(Photos provided by: Janet Hays)

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.