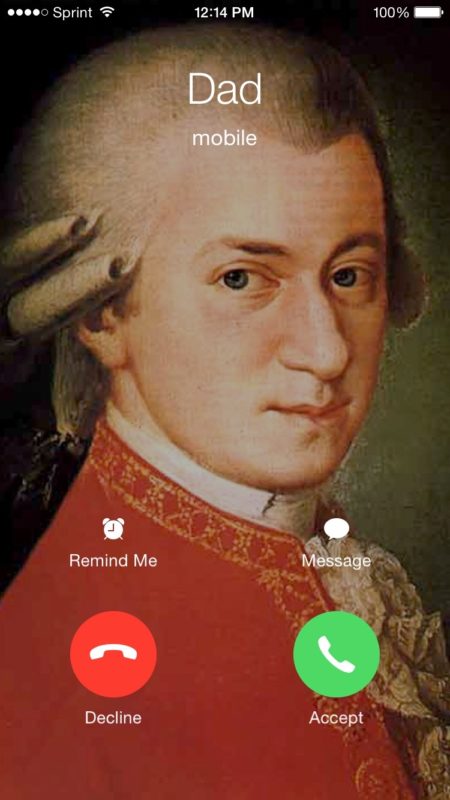

The first time I texted my dad, I sent him a simple yes or no question about getting a ride home from school. He had recently gotten an iPhone, so it seemed appropriate. He responded by calling me and leaving a voicemail: “Hey Lydia… Just wanted to let you know I got your text.” He never answered my question.

The first time I texted my dad, I sent him a simple yes or no question about getting a ride home from school. He had recently gotten an iPhone, so it seemed appropriate. He responded by calling me and leaving a voicemail: “Hey Lydia… Just wanted to let you know I got your text.” He never answered my question.

When I brought it up the next time I saw him, he said his thumbs are too big for that nonsense. Since then, I’ve learned that he does receive and open texts, but he won’t send one back, so I have to pick and choose what I’d like to blindly send his direction.

Then, last year I saw a familiar face in my Facebook suggested friends list. There sat a headshot of my dad, in the last place I’d expect to find him. After attempting to innocently stalk him, I learned that he has one friend, the only event on his timeline is him uploading a profile picture, and his profile picture has no likes. I sent him a friend request, my main hope being that I could add some pizazz to his timeline by liking his photo and upgrading his friend list to include two people, but he never accepted it. At first when I brought it up, he denied having a Facebook account. Eventually I was able to trigger his memory of making the account, but he insisted that he didn’t remember his password. To this day, my friend request has not been accepted.

My dad is by no means stuck in the stone age. As a graphic design and photoshop professor, he’s very familiar with the ins and outs of computers and software. Plus, he’s a gadget guy who loves a good deal on eBay, be it a fruit juicer or a home weather station. When it comes to the social side of technology, though, I certainly express a bit more enthusiasm than he does.

When I first got a cellphone for my 11th birthday, it was an imitation Razr flip-phone that ran on calls purchased minute by minute. I envied my friends who had mastered texting with the traditional numerical keys, and I quickly became addicted to Tetris. I couldn’t have been happier when I upgraded to a purple model featuring a touchscreen and a full sliding keyboard. I’d slide it in and out, in and out, listening to how it clicked. That’s when texting became a breeze, and my tiny thumbs had no problem typing away.

Facebook was huge in middle school, and the seventh grade consisted of three kinds of people: those who were 13 and old enough to legally have an account, those who were 12 and didn’t have an account, and those who were 12 and had sneakily made accounts behind their parents’ backs. When a friend learned I was a member of the lame second group, I buckled to peer-pressure and joined the edgy and elusive third group. But the guilt sank in, and soon after I sneakily disabled my account for safekeeping until I turned 13. Three years ago, it took the same friendly coercing to convince me to download Snapchat, and I’m still resisting the temptations of Instagram.

Meanwhile, my 15-year-old sister has never had a Facebook, and she has no desire to make one. She says hardly anyone her age does; their social lives instead revolve around Instagram and Snapchat, where images flash before their eyes and can be loved with two taps or cast away with one. To think it once took me four taps just to reach the letter “S” with my flip-phone.

My sister and I recently got into a sarcastic text-argument over who is more knowledgeable about memes. It was really more of an argument about whose generation is more internet-savvy. I fired an arsenal of both cats and socially conscious memes from my college’s student-run “WashU Memes for 1% Tweens” Facebook page (a self-deprecating joke about our pathetic rates of socioeconomic diversity), while she presented a carefully curated mixture that highlighted dogs and SpongeBob. In many of her memes, the punchline is that there is no punchline. But what I see as empty, she sees as meaningful, and what I see as meaningful, she sees as trying too hard.

My sister after convincing my dad to join Snap Chat with her (Photo by: Lydia Straka)

Truth be told, there is a substantial difference between how my sister and I interact with social media, even though she’s only three years younger than I am. Unless college forces her and her friends to join the bandwagon, I can only imagine Facebook will be obsolete among young-adults within the next decade. Of course, this is nothing compared to the differences between the two of us and my dad. But still, I sometimes feel the same resistance against Instagram boil inside of me that my father does when I question his Facebook presence.

We all need each other, though. Just this week, my dad asked me to show him how to use speakerphone while on hold with Apple support. Amidst the playful arguments I have with my sister, I admit that I am taught things of value: apparently calling dogs “doggos” isn’t cool or cute– it’s just annoying. There are moments, even, when I can learn from my dad. Last week he reminisced not about the clicking of sliding cellphone keyboards, but about the clicking of typewriter keys. We pieced together that the “shift” key on modern keyboards actually references how typewriters would physically shift up to access to capital letters. I had never given a second thought to what “shift” meant.

“We used to just send letters and occasionally make calls. And you know what, we survived,” he recently told me. As I see it, the essential part is not that we survived without current technology, but that we still survive and are still human with it.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.