From legacy to magazine to book to lessons learned (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

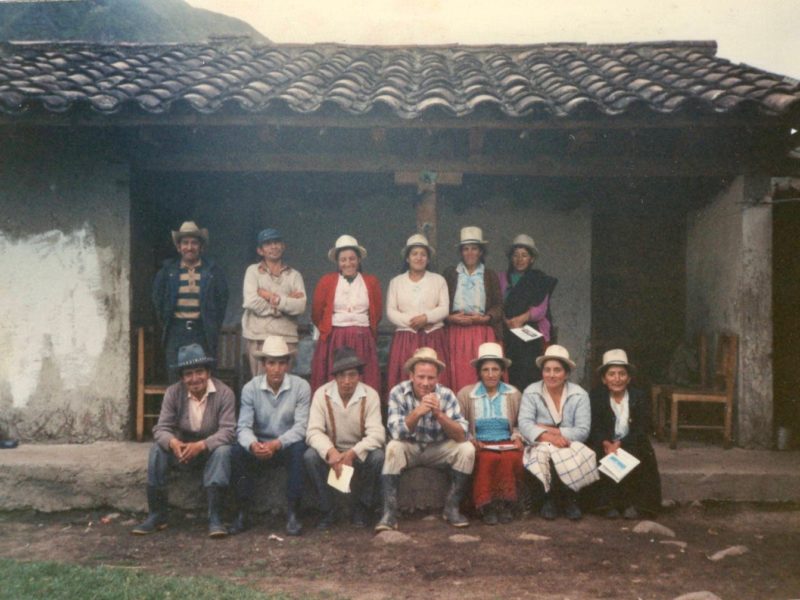

When I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Ecuador, the locals had a tough time pronouncing my unusual English name, Folwell. I tried the phonetic translation, Caer Bien, or, “Fall Well,” but, for obvious reasons, decided against it. Ultimately, I settled on Leonardo, after the famous Florentine artist. He had been one of my heroes growing up. Not surprisingly, people immediately started calling me, “El Joven, Leonardito,” or, “the young, little Leonardo.” I should have known that naming myself after a giant begged the diminutive.

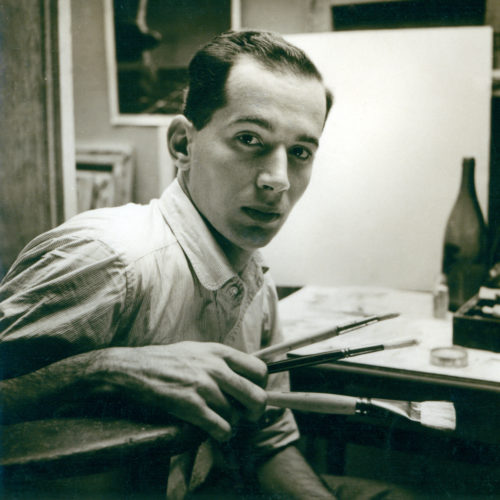

Many years later, I became the founding principal of an arts integrated elementary school. To inspire our young “apprentices,” I had our “master” teachers name their classrooms after their favorite artist. I named my office after my dad, George Dunbar, an amazing local painter and sculptor; but, my second choice was definitely Leonardo. To honor him, I designated the main sidewalk, “Da Vinci Way.”

As an educator, I read a lot of nonfiction. It is usually about pedagogy or instructional “best” practices. But, when I saw the new biography of Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson, I couldn’t resist. It was a much welcome diversion. And, as it turns out, it was chock-full (like da Vinci’s notebooks) of valuable lessons for teachers. The following are just a few of the many takeaways: *1

- Chart your own destiny. Leonardo da Vinci was the illegitimate child of a peasant woman and a notary. He grew up poor, and received almost no formal education. Throughout his life, he actually referred to himself as an “unlettered man.” Da Vinci was also gay at a time when homosexuals were not only discriminated against, but also imprisoned or even tortured. The odds of success were stacked against him. Leonardo overcame these challenges with grit and determination, confidence, skill, creativity and hard work. He was self-taught and self-motivated. He could have easily been the protagonist in a novel by Horatio Alger. He makes us realize that any child growing up under any circumstances could someday paint the next Last Supper.

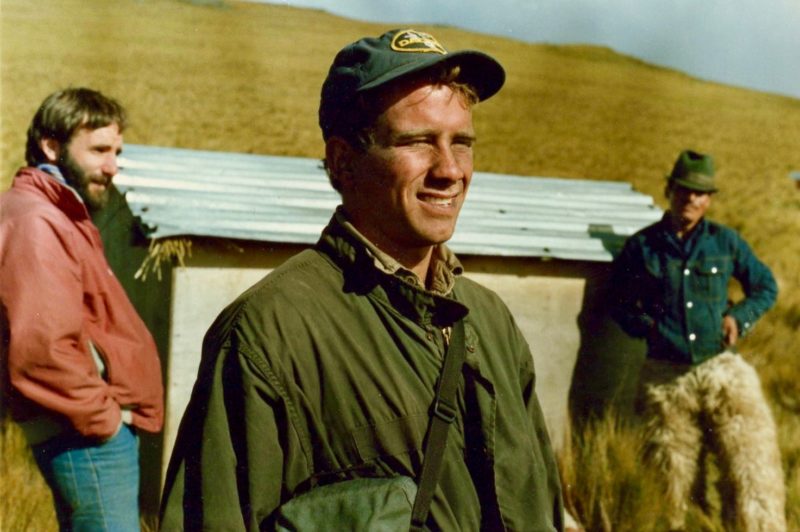

El Joven Leonardito (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

El Joven Leonardito (photos by: Folwell Dunbar) - Stay curious. Kids are curious from the get-go. “Why” is usually one of their favorite words. But, for some strange reason (We educators could be culpable?), many of them lose that curiosity as they grow older. Da Vinci never did. He remained curious, relentlessly curious, his entire life. Even on his deathbed, he was trying to figure out a puzzling geometry problem – until, of course, he famously discovered that “the soup was getting cold.” Leonardo wanted to know why the sky was blue, how to square a circle, why marine fossils could be found on the top of mountains, how blood flowed throughout the body, what muscles controlled the expressions on our lips, how our eyes processed light, and why birds could fly. His curiosity fueled his creativity; and, it propelled him to do great things. As educators, we need to find a way to keep our kids (and ourselves) curious – like da Vinci!

- Observe your surroundings. To satiate his voracious curiosity, da Vinci carried a notebook with him wherever he went; and, he recorded whatever he saw. From the beating wings of a dragonfly to the swirling eddies in rivers and streams, from cascading ringlets of hair to the long, barbed tongue of a woodpecker, from tiny veins and capillaries to the blurry intersection between light and shadow, he obsessed over the details most of us ignore. He then converted those observations into revelations about optics, engineering, geography, archeology, physics, and biology. And, of course, he also used them to create magnificent works of art. We need to challenge our students to use their senses, all of them, each and every day.

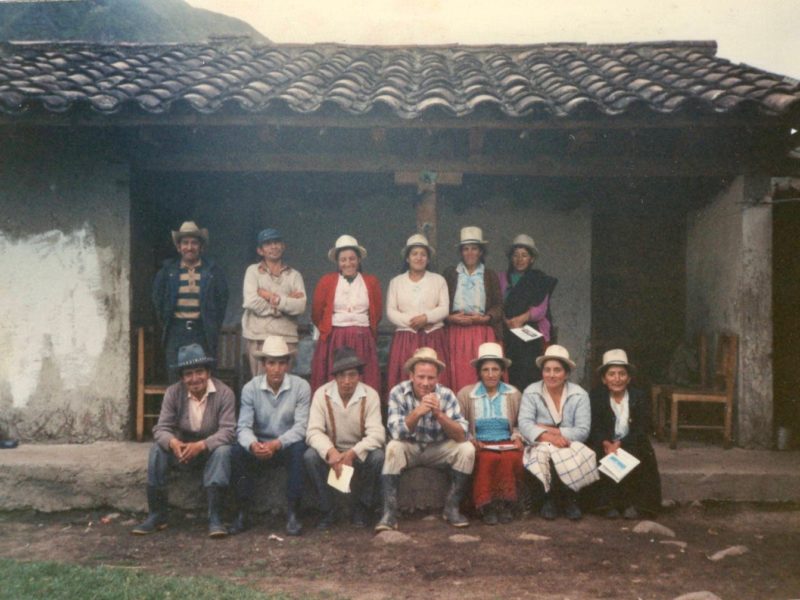

From New Orleans to Ecuador, education as the ticket (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

- Tell stories. Great storytellers have to describe characters and settings; and, they have to deliver a convincing narrative filled with believable conflicts and resolutions. Da Vinci was definitely a great storyteller. He used his powers of observation to accurately (and beautifully) capture gestures, expressions, movements, and emotions. From The Battle of Anghiari to The Last Supper, Leonardo painted (directed and choreographed) stories filled with physical and psychological drama. To be effective teachers, we need to do the same thing with our curriculum. And, we need to help our “understudies” become proficient in the art of storytelling as well.

- Combine disciplines. Finland recently decided to do away with subject-specific courses. Five hundred years earlier, da Vinci had the same idea. He blurred the lines between geometry, physics, biology, engineering and art. He used his discoveries from one field to support his work in another. For example, the Mona Lisa’s famous, enigmatic smile is grounded, or better yet, glazed in the science of optics. (See the recent cover article in The Atlantic.) Vitruvian Man, his sketch of a fetus in the womb, the Lady with an Ermine, his designs for flying machines and deluge series all combine elements from different disciplines. Being well-rounded made Leonardo the poster child for the Renaissance; being well-rounded makes us better teachers.

- Teach through analogies. Because of his familiarity with different disciplines, da Vinci was able to see patterns and make connections. For example, he compared the womb to a seed and veins to the roots of a tree. He explained complex concepts by relating them to things we could all understand. In the classroom, teachers do the same thing. They explain math with music, they expose geometry through art, and they compare historical events to sports and nature. Like Leonardo, they teach (and learn) through analogies.

Folwell with students in Ecuador (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

- Learn through experience and experimentation. Long before Galileo, Bacon and Newton, Leonardo employed elements of the scientific method. He came up with theories and tested them by making observations and conducting experiments. He collected and used data, he looked for parallels in other disciplines, he drew designs and built models, he made graphic organizers and mind maps, and he brainstormed and collaborated with colleagues. He was thorough, persistent, and undaunted. He learned by doing – just like we (and our kids) do.

- Seek out and solve problems. Like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Edison, da Vinci was obsessed with building a better mousetrap. He designed bridges, wheelbarrows, walls, drains, fortresses, musical instruments, weapons and cathedrals. He devised a way to cast a massive equestrian statue; he conceived water diversion projects to drain swamps and to prevent flooding; he envisioned planes, tanks, helicopters and submarines; he drafted blueprints for a utopian city; and he drew detailed aerial maps before cartographers could fly. Like all great innovators, he combined science and art with fantasy and imagination. (He employed 21st century skills five hundred years before we had even coined the term.) Obviously, there are still plenty of real-world problems. We need to challenge our budding Leonardos to solve them.

- Focus on quality. In 1480, da Vinci started painting St. Jerome in the Wilderness. But, he wasn’t satisfied. Twenty years later, after having dissected numerous corpses and having made countless anatomical drawing – some of which are still referenced in medical schools today – he amended the work. But, he still wasn’t satisfied. Da Vinci was a perfectionist, perhaps to a fault. Many scholars have criticized him for spending too much time trying to “get things just right.” In other words, “If da Vinci had lowered his standards, he could have been more productive.” But, if that had been the case, he probably would not have spent sixteen years working on the Mona Lisa, considered to be the greatest painting of all time. Without high standards and a relentless focus on quality, our kids will never reach their full potential.

- Enjoy the journey. According to KIPP, “Knowledge is power.” According to companies like Alphabet and Amazon, it is also tremendously profitable. According to Leonardo da Vinci, knowledge was enlightening. And, it was exhilarating. He pursued knowledge for its own sake. Like figuring out a crossword puzzle, or creating a mandala (or, reading Isaacson’s book on da Vinci for that matter), there is satisfaction in the process of discovery. Too often, our kids study to pass a test, to win a prize, or to avoid getting in trouble. Wouldn’t it be nice if they just studied to learn?

Reading about Leonardo da Vinci is an exercise in humility. It makes us all feel terribly inadequate, like we need to add “joven” or “ito” to our names. But, it is also inspiring. It makes us realize what we are capable of. Hopefully, his example (and lessons) will motivate us (and our students) to pursue our own masterpiece.

* Full Disclosure: At the end of the book, I discovered that Walter Isaacson had listed his own take-aways. While I actually wrote these before I read his, there is some overlap. I’d like to think that “great minds think alike,” but, that would be like naming myself after Leonardo da Vinci.

-

- Folwell’s father, George Dunbar (photos provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

-

- Folwell’s father, George Dunbar (photos provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

Folwell Dunbar is an educator, a writer, and, in the spirit of one of his Renaissance heroes, a dabbler. He can be reached at fldunbar@icloud.com

El Joven Leonardito (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

El Joven Leonardito (photos by: Folwell Dunbar)

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.