Considered the second American war of independence, the War of 1812 threatened to eradicate our young nation’s hopes of expansion and hegemony within the continent. Culminating in the seizure and burning of Washington, D.C. in August of 1814, the war posed the greatest challenge to the United States of America since its founding. Indeed, the United States was squaring off against the world’s preeminent naval force—Great Britain.

Although peace was achieved with the Treaty of Ghent in December of 1814, the most decisive engagement of the war had yet to take place—the Battle of New Orleans. A vital strategic holding, New Orleans encompassed the mouth of the Mississippi river. If the British were to capture New Orleans, they would control any hope of expansion into the Louisiana territory as well as the river itself—an indispensable element of American trade and industry. British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh exemplified such ideals when he stated that Americans would be “little better than prisoners in their own country” if the British were to capture New Orleans.

Defending the city from the oncoming British naval forces appeared to be an insurmountable challenge. Major General Andrew Jackson, however, was up to the challenge. With an impenetrable will, Jackson led his men to a resounding victory, driving out the British in retreat on January 18, 1815.

Jackson would go on to become our seventh President, and to this day he remains a fundamental part of New Orleans history. The city honored Jackson by renaming the Place d’Armes as “Jackson Square” in 1815. Jackson’s presence within the city, however, ceased with his decisive success over the British, for he returned home to Tennessee shortly thereafter.

During his brief time in New Orleans, Jackson resided within a building in the French Quarter. It was in such building that Jackson planned his defense of the city of New Orleans against the oncoming British forces. To this day, however, the location of said building has been unknown. Intrigued, I set out to locate Andrew Jackson’s headquarters.

The earliest source referring to Jackson’s headquarters comes from Major Arséne Lacarriére Latour who, in 1816, published his work, Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814-15. Latour states that Jackson “established his head-quarters” upon arriving in New Orleans, but Latour neglects to identify the specific address or general location of such headquarters (Latour, 52). In Alexander Walker’s work, Jackson and New Orleans, published in 1856, Walker uses firsthand accounts of the events which took place in the winter of 1814 into 1815, depicting Andrew Jackson throughout the Battle of New Orleans. Walker states how, after arriving in the city, Jackson “proceeded to the building, 106 Royal Street” and hung a flag from the third story window, indicating “to the population the headquarters of the General” (Walker, 18). Due to Walker’s account, numerous historians later referred to 106 Royal Street as Andrew Jackson’s headquarters.

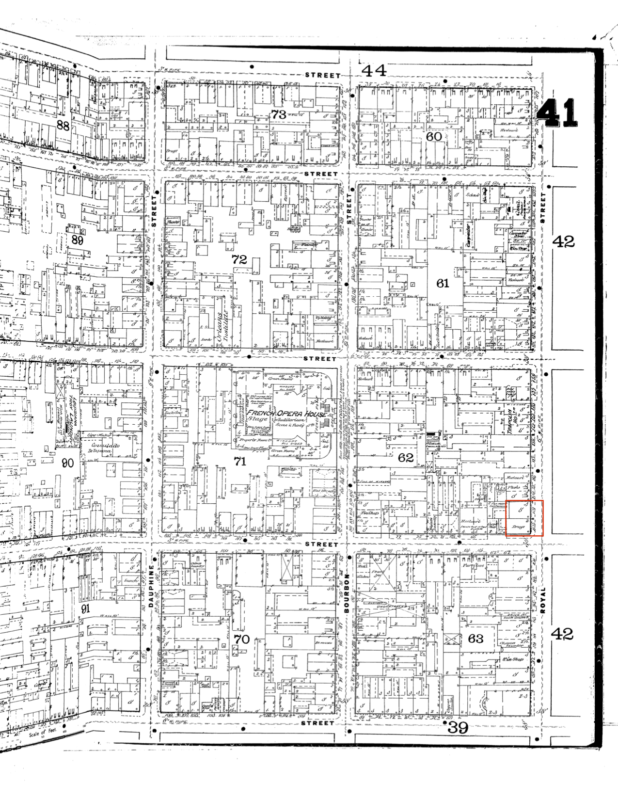

Upon reading this, I visited 106 Royal Street in the French Quarter, which today is occupied by the souvenir shop “Gator Country.” However, upon further examination, I realized that, like those historians before me, I had neglected to take into account that New Orleans street numbers had changed in the 1890s. Before this, there had been no standard method of numbering street addresses in the city. Jackson and New Orleans, the source tying Jackson’s headquarters to 106 Royal Street, was written in 1856—years before the addresses in the French Quarter were re-numbered. The Sanborn insurance maps for New Orleans, drawn up in 1885, include street addresses prior to the change. There is no record, however, of 106 Royal Street.

Likewise, the “Alphabetical and Numerical Index of Changes in Street Names and Numbers, Old and New, 1852 to Current Date [1938],” drawn up by Gray B. Amos in 1938 as a part of the Works Progress Administration, does not include 106 Royal Street. Looking at the Sanborn insurance map (Vol. 2, Sheet 41 B) from 1885, one can see the addresses 105 and 107 Royal Street listed, located on the corner of Royal and St. Louis. Amos’ index lists these two addresses as the modern equivalents to 501 and 505 Royal Street. Such is corroborated by comparing a present-day map of the French Quarter with that of 1885.

“Sanborn Insurance Map Sheet 41 B,” 1885.

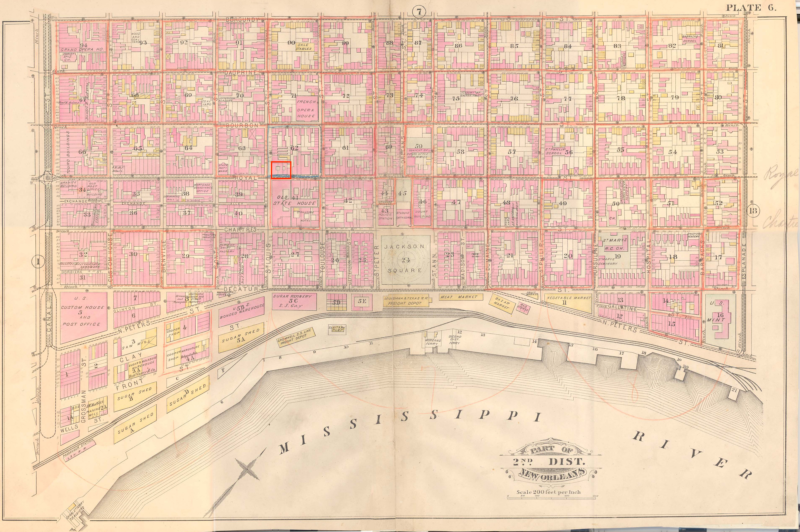

Similarly, the Robinson Atlas of 1883 depicts the French Quarter with numbered addresses. The Robinson Atlas places 105 and 107 Royal Street at 501 and 505 Royal Street. I then sought to examine the title records for these parcels. Given the difficulty of locating title records for these parcels, many of which are more than two hundred years old, as part of my preliminary research, I engaged the assistance of local real property title abstractor, James Lapeyre, who pointed me to the Historic New Orleans Collection’s Collins C. Diboll Vieux Carré Digital Survey.

The Diboll Digital Survey provides a title chain for 501 and 505 Royal Street—which were 105 and 107 Royal Street before the 1890s. This online database contains title information for the Royal Street lots dating back to January 1, 1722, when the lots were owned by the Company of the Indies. The lots were later transferred to King Louis XV.

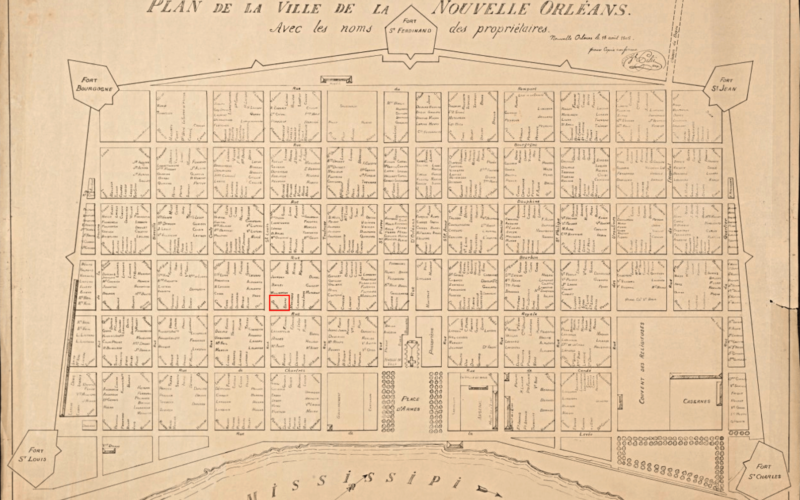

From the years 1808 to 1811, the lots were owned by Charles Baronee Dufau. The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 1808 map of the French Quarter by Gilbert Joseph Pilié lists the owners of each site within the quarter, and Dufau’s name is listed in the locations which would have been 105 and 107 Royal Street at the time, thereby corroborating that 105 and 107 Royal Street prior to the re-numbering are the same parcels as today’s 501 and 505 Royal Street. Dufau sold both sites to Pierre Joseph Maes in 1811, and Maes owned the property throughout the time Andrew Jackson was in New Orleans.

“Robinson Atlas,” 1883.

“Plan de la Ville de la Nouvelle Orléans,” 1808.

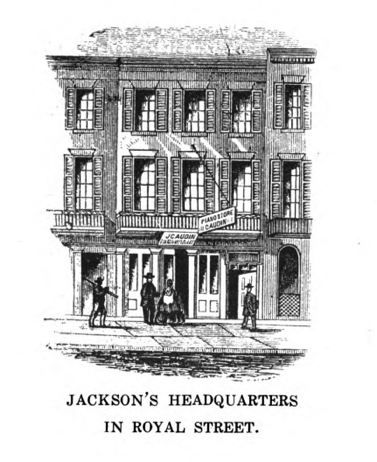

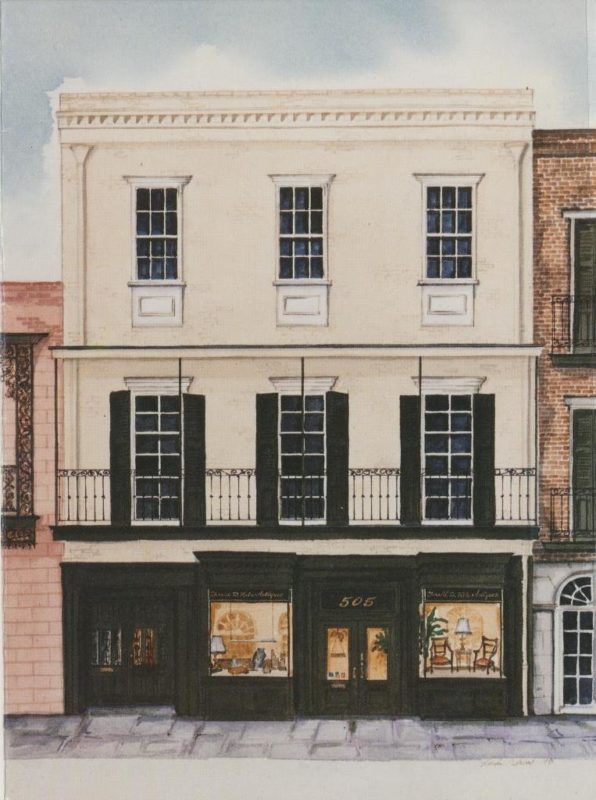

In 1811, 105 and 107 Royal Street are described as “measuring together 61’ front on Royal Street by 78’ deep and front on St. Louis Street” according to the Historic New Orleans Collection. Likewise, in 1833, 107 Royal Street was described in the title chain as having identical dimensions, with the added description of “four apartments, two cabinets, one gallery, a courtyard, kitchen,” which remains the same in the property’s description in 1861 and even as late as 1999. In a source from 1915, The story of the Battle of New Orleans, by Stanley Clisby Arthur, which was issued as part of the official program for the ceremonies commemorating 100 years since the Battle of New Orleans and 100 years of peace between Great Britain and the United States, I found a sketched image, described as 106 Royal Street, which has “Jackson’s Headquarters in Royal Street” written below it. The image—a building—is a nearly identical match to the present building located at 505 Royal Street. This drawing not only names the building at Royal Street as Jackson’s headquarters, but the drawing of the building also appears to be the same as later drawings and photographs of 505 Royal Street. Some cross-over is starting to occur, which means we could be walking the path to Jackson’s headquarters right now.

From The Story of the Battle of New Orleans, 1915.

505 Royal Street, Present Day.

505 Royal Street, 1985.

The Library of Congress contains a photograph from 1901, described as the “Courtyard of Home of Mrs. M.E.M. Davis, New Orleans, LA., Jackson’s Old Headquarters.” From the historic plaque mounted on the front of the building located at 505 Royal Street today, which states that Mary Evelyn Moore Davis “lived in the second floor residence,” we know that the present building was the home of Davis in the early part of the last century. Similarly, in an edition of the Times-Picayune from January 2, 1909, it is said that Moore “died at her home, 505 Royal Street.”

“Court Yard of Home of Mrs. M.E.M. Davis, New Orleans, La., Jackson’s Old Headquarters.” Detroit Publishing Co., 1901.

Ultimately, I believe that the current site of 505 Royal Street was Major General Andrew Jackson’s headquarters from December, 1814 to January, 1815, from which he planned the defense of New Orleans from the impending attack by the British.

I understand that 106 Royal Street is commonly referred to as General Jackson’s headquarters, but I believe that his headquarters was actually located at 107 Royal Street—the present day 505 Royal Street. Because there was no systematic approach to numbering addresses in the French Quarter—evident by the need to completely re-number the city in the 1890s—it is likely that Alexander Walker, the first to identify the address of Jackson’s headquarters as 106 Royal Street, was slightly off in his information, and should have rather stated 107 Royal Street.

Because Walker is the earliest source to provide a number for Jackson’s headquarters, writers and historians since have taken his word as true. Based upon a review of all of the maps created before 1890 of the French Quarter located within the Library of Congress, the Historic New Orleans Collection, Tulane University’s Howard Tilton Memorial Library, and a variety of other sources, 106 Royal Street does not appear to have existed. Likewise, when analyzing city records of address changes in the 1890s, 106 Royal Street is not listed. Therefore, I believe that 107 Royal Street was truly the location of Jackson’s headquarters during the Battle of New Orleans, and today this same location is known as 505 Royal Street.

The Battle of New Orleans was the decisive victory that America needed. Through the leadership of Major General Andrew Jackson, the American frontier was able to expand westward, refusing to halt due to any British intervention. Jackson’s headquarters on Royal Street, in the French Quarter, was home during this time. We must value 505 Royal Street as the fundamental historic landmark that I believe it is—the headquarters of Andrew Jackson. For had Jackson not repelled the British during the Battle of New Orleans, we would be living in a very different nation today.

Sources

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.