In celebration of the city’s Tricentennial, NolaVie and New Orleans Historical bring you the series Who Did it Better: New Orleans Then and Now. In it, we look at aspects of the city’s history and their parallels in the present. Today we go to the city’s literary history, in a segment we’ll call Wags and Words.

With the annual Tennessee Williams Literary Festival on the horizon — March 21-25 — thoughts turn to the generations of writers who have passed through New Orleans. For 300 years, the Big Easy has provided inspiration and backdrop for a long parade of authors.

One of the first to pen his thoughts was American architect Benjamin Latrobe. Upon arriving here in 1819, he wrote that “New Orleans has at first sight a very imposing and handsome appearance, beyond any other city in the United States in which I have yet been.” Then reality set in. His next observation went like this: “Mud, mud, mud. This is a floating city, floating below the surface of the water on a bed of mud.”

Mud or not, New Orleans sent out a siren call to those willing to listen.

Tennessee Williams (Photo: Orlando Fernandez, World Telegram staff photographer. Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection.

As Tennessee Williams would put it some 250 years later, “In New Orleans … I found the kind of freedom I had always needed, and the shock of it – against the Puritanism of my nature – has given me a subject, a theme, which I have never ceased exploiting.”

Ignatius J. Reilly, in John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, echoed the sentiment. “Leaving New Orleans also frightened me considerably. Outside of the city limits the heart of darkness, the true wasteland begins.”

Native New Orleanian Grace King was one of the most ardent chroniclers of the local environment. Born to a wealthy New Orleans family in 1852, she had deep loyalties to her Creole heritage, and said that she wrote from “a sort of patriotism–a feeling of loyalty to the South.” Her prose was as lush as the settings she described: “We wander through old streets, and pause before the age stricken houses; and, strange to say, the magic past lights them up.”

More than a century later, Anne Rice recaptured that sense of magic. “In the spring of 1988, I returned to New Orleans, and as soon as I smelled the air, I knew I was home. It was rich, almost sweet, like the scent of jasmine and roses around our old courtyard. I walked the streets, savoring that long lost perfume.”

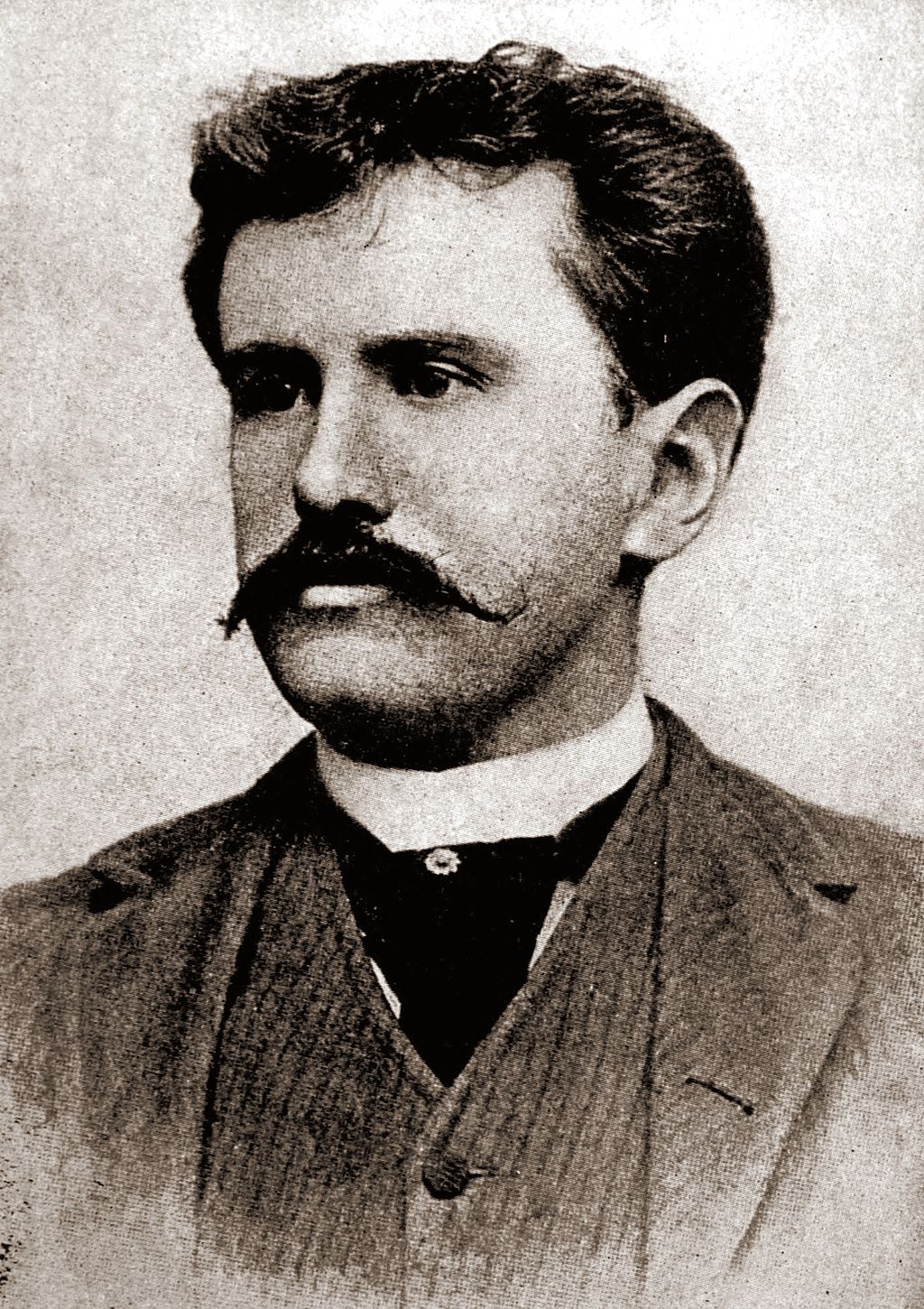

O. Henry, nicknamed at a New Orleans bar (Photo: Gutenberg.org.)

Tennessee Williams was another writer evocative about his New Orleans surroundings. His play “Vieux Carre” is based so profoundly on his Toulouse Street apartment here that critics have said that the house itself is the work’s true protagonist. One scene in the play supposedly recalls a real incident, when Williams’ landlord became frustrated about a loud party going on downstairs. So she poured boiling water between the floorboards. Someone called the police and everyone, including Williams, went to night court.

Today, Williams’ Toulouse Street digs are owned by the Historic New Orleans Collection, where you can find a 1973 manuscript of “Vieux Carre.”

Iconic New Orleans settings abound, of course. The Hotel Monteleone alone has been in, at last count, 173 novels and stories. Truman Capote went one better, claiming to actually have been born in the Monteleone. Actually, his mother went into labor while staying at the hotel and just made it to Touro in time to deliver baby Truman.

For many writers, New Orleans was not merely about place, but culture. “Blessed be these people,” Sherwood Anderson wrote in 1922 from his third-floor apartment in the French Quarter. “They know how to play. They are truly a people of culture.” In New Orleans, he said, he found the leisure and charm that he felt the nation had lost: the value of “putting the joy of living above the much less subtle and … altogether more stupid joy of growth and achievement.”

For writers, New Orleans is not at the edge of the world, but at the center of it. According to short-story writer O. Henry, there are “only two cities in the world – New York and New Orleans.” And it was the latter that gave O. Henry his pen name. In 1896, as William Sydney Porter, he was indicted for embezzlement in Austin, so he hopped a train for New Orleans. He began writing for local newspapers, and socializing with other reporters at local bars. During one boozy evening at the Tobacco Plant Saloon, patrons began calling out to the bartender, “Oh, Henry, another of the same!”

That bar theme continues. O.Henry’s former home on Bourbon Street is today the Bourbon Cowboy, where patrons may not find a bartender named Henry, but they can ride a mechanical bull.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.