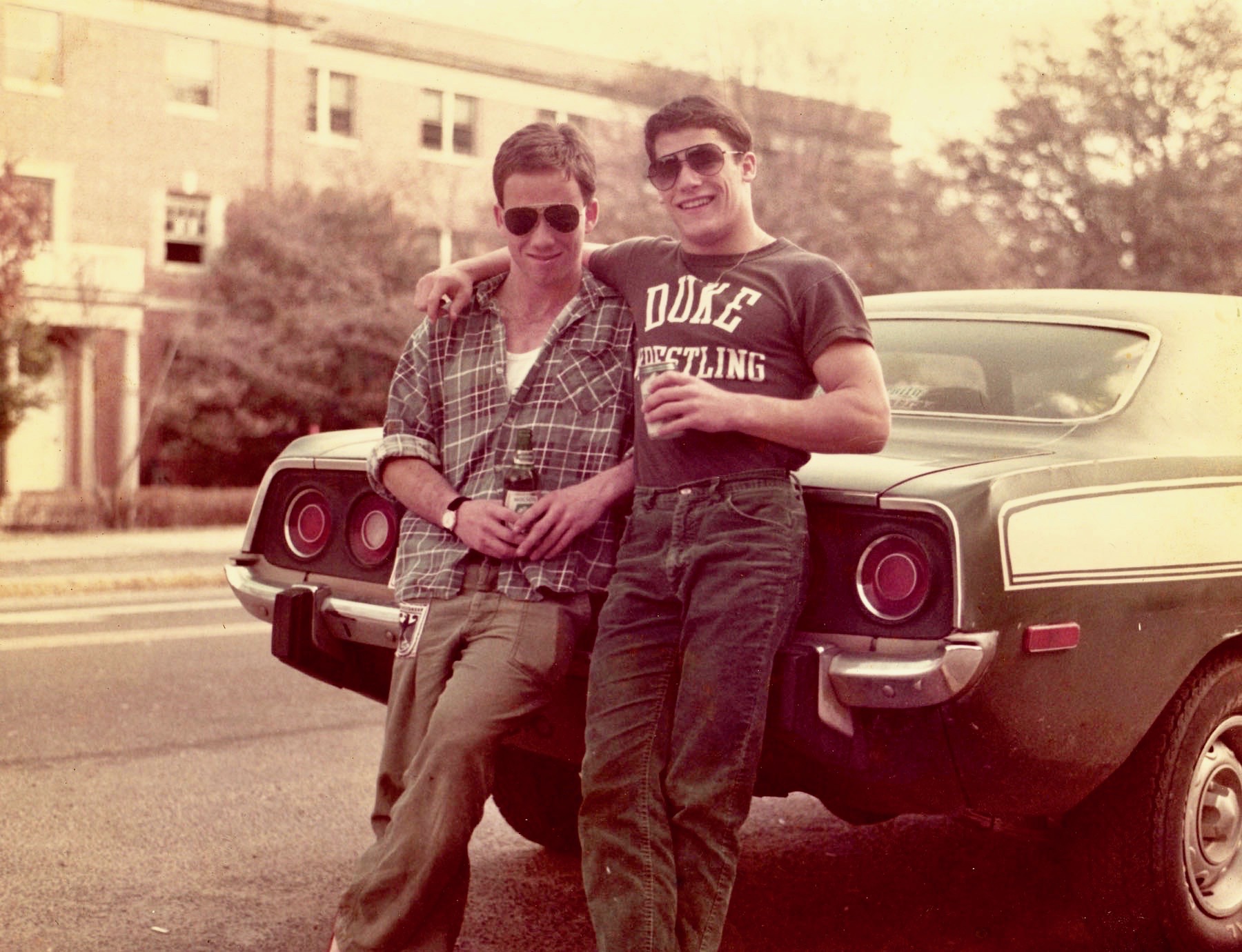

Folwell, Chuck, and the Barracuda (photos courtesy of: Folwell Dunbar)

Folwell, Chuck, and the Barracuda (photos courtesy of: Folwell Dunbar)

My freshman year in college, I was assigned two roommates. One was a 15-year-old from Beijing, who was on a full academic scholarship. He was the Asian version of Doogie Howser. His sole possessions included a small backpack containing a single change of clothes, a Casio watch with a built-in calculator, and a first edition copy of The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA by Dr. James D. Watson. My other roommate was the sheltered, only child of a wealthy New York socialite. His name was Augustus, and he looked like he could have been the cover model for the classic 1980 field guide, The Official Preppy Handbook. Augustus had never been away from home, so, for the first week and a half, he simply lay in bed whimpering like an abandoned puppy.

The two caused me to seriously question the validity of the roommate placement survey I had filled out over the summer.

Fortunately, I had a wrestling teammate who was in a similar predicament. Chuck’s assigned roommate was a self-proclaimed geek, long before it was popular to make such a proclamation I might add. Whenever he wasn’t studying computer science on Science Drive, he could be found cloistered in the school’s dungeon-like video arcade playing Space Invaders, Ms. Pac-Man or Galaga.

Chuck and I quickly arranged for a trade.

Charles (Chuck) Egerton was from Baltimore. At 142, he was only one weight class above me, but he was built like a Sherman tank. He looked like a slightly smaller version of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. Though we were already well into the 80’s, Chuck was firmly ensconced in the 70’s. He wore terrycloth shirts with huge collars and tight designer jeans, he listened to Rush, The Eagles, Queen and Lynyrd Skynyrd, he collected Lava Lamps and black light posters, and he drove a puke-green Plymouth Barracuda with white racing stripes.

As I would soon discover, Chuck was also an extremely successful Lothario. Because of this, I spent much of my freshman year sleeping on a couch in the common room. Needless to say, the arrangement was not exactly conducive to good study habits. It made for a tough year.

I learned a valuable lesson though: solutions, especially those that seem obvious at the time, can actually cause their own problems. It was the first of many extracurricular lessons I would discern far, far from the classroom. The following are just a few of the others:

A Close Shave

I was a short-order cook at a college bar. We served hamburgers, hoagies, cheese fries and onion rings. Late one night, I got slammed with a huge order of cheeseburgers. I threw a few patties on the grill and buttered some buns – everything tastes better with butter –before I realized that we were out of cheese. I ducked into the walk-in freezer, grabbed a huge block of cheddar, and started cutting it on the large, stainless steel industrial slicer. Every time I slid the block over the spinning blade, it made the sound Sha-shunk. Sha-shunk, sha-shunk, sha-shunk…

Watching the patties on the grill and listening to the soothing sound of the slicer, I thought about the biology test I had the next day, an upcoming wrestling match against Clemson, and a cute girl I had met the night before at a sorority party. Then, I heard a different sound. It was an abrupt and disturbing, Ka-Chunk!

The carnage from the blade (photo courtesy of: Folwell Dunbar)

I felt a sharp pang in my right hand. I fired off a bevy of expletives and turned toward the machine, where I saw a geyser of what I had hoped was ketchup spurting up high into the air. If I were describing the accident today (which I am), I would definitely reference the derrick scene from the apt titles film, There Will Be Blood.

Without looking at what was surely a gruesome wound, I lunged for my mangled hand and quickly wrapped it up in reams and reams of paper towels.

“Apply pressure,” ordered the barback as she burst into the kitchen!

Sensing my apprehension, she added in a voice like Ally McBeal’s, “Don’t worry, I’m pre-med.”

Inspecting the floor and not my hand, she said, “You’ve obviously lost a great deal of blood. You’ll definitely need a tourniquet.” She pulled out a dirty dishtowel from her apron and tied it tightly around my wrist. “If we hope to save the severed digit,” she continued, “you’ll need to keep it on ice.” She filled a plastic bag with cubes from the well and attached it to my hand with an entire roll of Saran Wrap. “Now, get to the hospital,” she said!

Pleased with her triage, the barback returned to the floor to retrieve empty beer bottles and soiled paper plates.

With my cocooned hand in tow, I jumped into my manager’s Dodge Dart and we raced – about as much as you can possibly “race” in a Dodge Dart – toward the Duke University Medical Center.

On the way over, I pleaded with my boss, an 11th-year senior, “We have to save my finger! If we don’t, I’ll never play guitar again!”

“But you don’t play guitar,” my manager pointed out.

“Yes, but I plan to learn,” I said.

“Jerry Garcia’s missing a finger,” he said. “And so is Mac Rebennack, better known as Dr. John. They seem to do just fine.”

“Good point,” I said, “but I’d still like to keep the finger.”

When we arrived at the hospital, I ran into the Emergency Room screaming, well, “bloody murder!” I pushed past a man having a heart attack, I cut in front of a woman who had been in a terrible automobile accident, and I barked at a guy who I’m pretty sure later became a homicide victim.

“Doctor, doctor,” I screamed!

“Gimme the news,” chimed in my manager, “I got a bad case of lovin’ you!”

“Not funny,” I said. “I may have lost my finger – or possibly even my entire hand! Please doctor, do what you can to save it!”

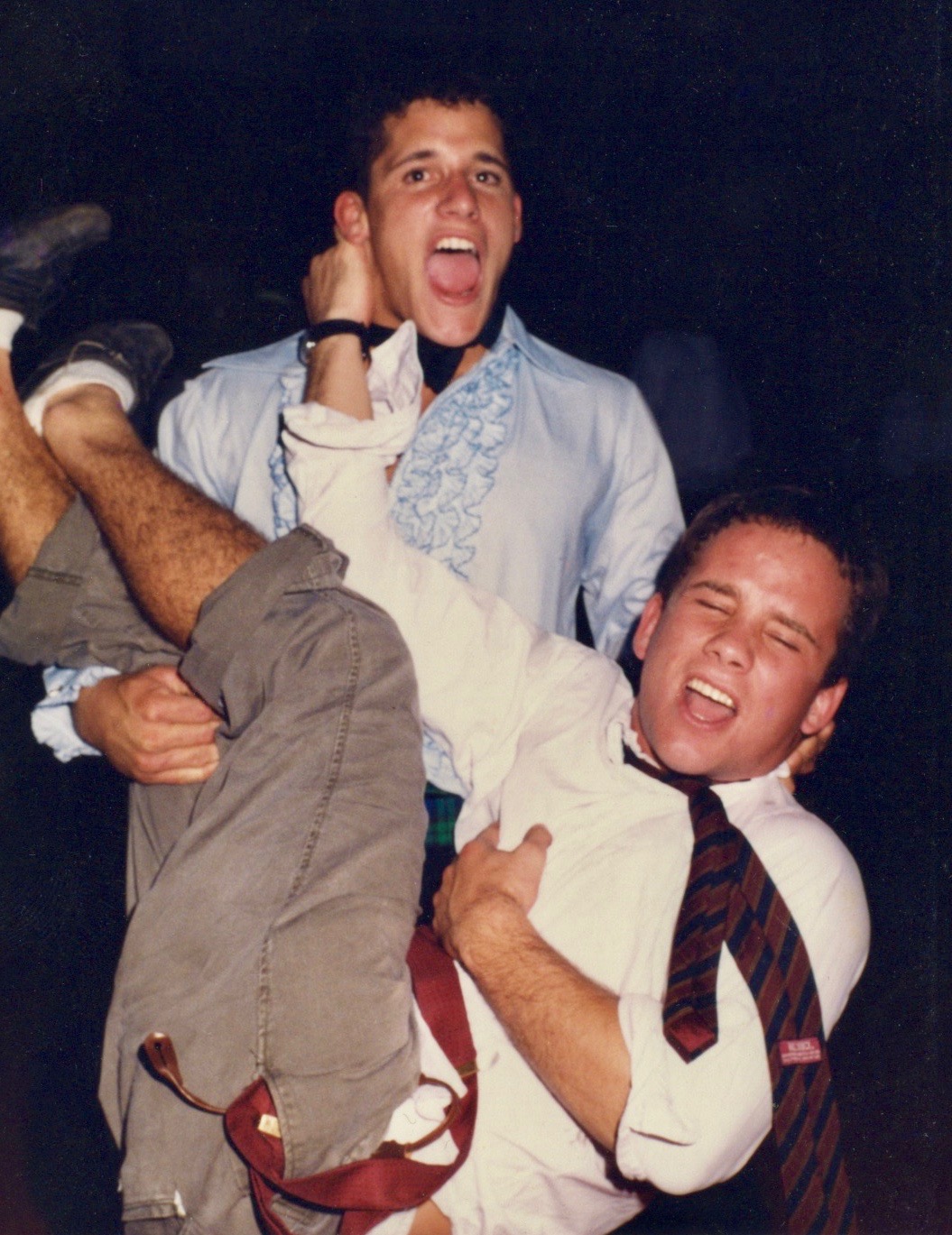

Being rescued by Chuck from a non-slicer related calamity (photos courtesy of: Folwell Dunbar)

“Well, let’s take a look,” he said. The ER doctor pulled out a pair of scissors the size of garden shears and starting cutting away at my makeshift bandages.

A small crowd had gathered around like rubberneckers eager to witness the sure-to-be hideous carnage within.

When the doctor finally reached my hand, there was a collective sigh of disappointment from the crowd. They looked like trick-or-treaters who had just been given a box of old crusty raisins.

The small wound on the tip of my right index finger was the size of a single hole-punched paper chad. The missing skin was about the width of, well, a thin slice of sharp cheddar cheese.

“If you would like,” said the doctor, “I could give you a Band-Aid.”

“No, that’s ok,” I said with air of stoicism. “It’s just a flesh wound.”

During my biology test the next morning, I remember scribbling in the margins of my blue examination book, “Know the facts before you (over)react.”

Note: The rest of the extracurricular lessons, “Cat on a Hot Dorm Roof,” “They Call Me the Streak,” and “Petuahua,” along with other survival tales, can be found in Folwell’s upcoming book, He Falls Well.

Folwell Dunbar is an educator, artist and former short-order cook. He can be reached at fldunbar@icloud.com

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.