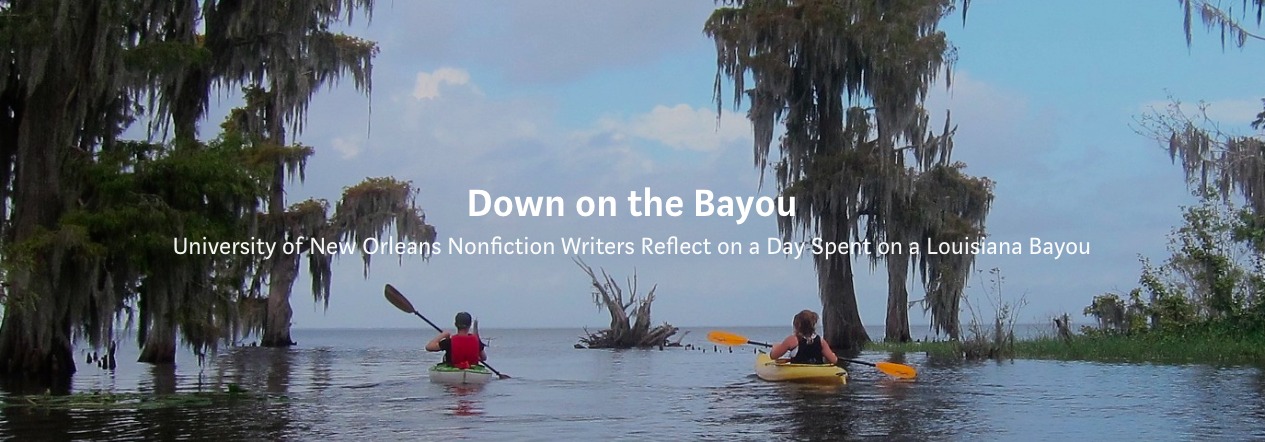

Students kayaking down the bayou for Richard Goodman’s MFA creative nonfiction workshop. (Photo from: Down the Bayou website)

Editor’s Note: Liz Brina took part in Richard Goodman’s Master of Fine Arts nonfiction writing workshop at the University of New Orleans, where the students take a kayak trip down a southeastern Louisiana bayou in order to observe the issues and conditions that make the bayous beautiful and precarious. Once they finish their full-day kayaking adventure, the students reflect and write, creating pieces that encapsulate their experience and give new awareness about the bayous. ViaNolaVie will be running these pieces as a continued series every week, and you can also read more student writing here and here. And now for Liz Brina’s “If We Can Build a Wood Box.”

Elizabeth Brina, writer through the MFA nonfiction workshop at University of New Orleans. (Photo provided by: Elizabeth Brina)

We are sitting in kayaks, floating down the Shell Bank Bayou, roughly thirty-five miles northwest of New Orleans. John, our guide for the trip, points to an object that resembles a tiny house. One foot high, half a foot wide, with a slanted roof and a baseball-sized hole carved in the front, suspended by a long metal pole and hovering above the water. “That’s a wood box,” John says. “People build them so that wood ducks have a place to nest.” I look around and see a few more wood boxes speckled along the shore. “See that green cone wrapped around the bottom of the pole? That’s to keep snakes out.”

These boxes mimic the natural cavities usually found in tree trunks that wood ducks instinctively use for nesting. These boxes are part of an extremely successful effort to restore the wood duck population, once endangered during the early 1900s due to drastic loss of forested wetlands. Now the wood duck, one of North America’s most colorful waterfowl — green head, rust-purple neck, gold and blue and black and white striped wings — is one of Louisiana’s most common birds.

Huh, I think to myself. Maybe us humans can do something right.

About two hours before we began paddling, my creative nonfiction workshop, eight graduate students from New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, Canada, Texas, and can’t forget our lone local from Baton Rouge, crammed the dining room of Bob Marshall’s home in Uptown New Orleans to listen to a presentation. Bob Marshall is a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist who writes about environmental issues related to the fragile coast of Louisiana, and he sure does know his stuff. It was barely past nine o’clock on a Saturday morning, I hadn’t finished my large iced coffee from CC’s yet, and I was already terrified.

Seven thousand years ago, the ground supporting Bob Marshall’s dining room floor did not exist. The Mississippi River, a vast expanse of moving water that ascends from Lake Itasca in Minnesota, then flows south through ten states, carrying sediments collected from tributaries merging with the mighty river anywhere between the Rocky and Appalachian Mountains, eventually spilling out into the Gulf of Mexico, depositing soil, stacking dirt and mud, for centuries, until finally, voila: a diverse and intricate ecosystem comprised of four million acres known as the wetlands. But what took Mother Nature seven thousand years to create, only took us humans eighty years to destroy. One third of the wetlands are gone. And they keep vanishing. These wetlands and everything that depends on them, including thousands of plant and animal species, and two million residents, not to mention ninety percent of the nation’s energy production, disappear at the rate of a football field an hour, sixteen square miles a year.

So how exactly is it our fault?

First, the levees. After the Great Flood of 1927 that left 600,000 people homeless and 500 people dead, we decided this could never happen again. We constructed walls around the river — we “put the monster in a strait jacket” as Bob Marshall more energetically explained — to protect communities from future flooding. However, these walls prevent new soil from replenishing an ever-sinking land. The wetlands could have survived just that though. If all the interference we managed were restricted to just levees, then subsistence, the natural process of land sinking, would account for mere millimeters a year.

Except in 1932 oil was discovered in those wetlands. Since then, 50,000 offshore wells have been erected, 15,000 miles of canals, 15 feet deep and 150 feet wide, have been dredged. The canals are giant holes we dug, big gaping wounds in the land. The canals allow pipes filled with oil to enter the interior but they also allow salt water to invade fresh water, killing plants and trees with precious roots that once held the soil together. And without plants and trees to slow and soften the wind, the wind erodes the soil even further.

And because of climate change, which is also our fault, sea levels are rising.

If we don’t do something soon — and fast — the ground supporting Bob Marshall’s dining room floor could be on the verge of open water within the next lifetime.

So we came up with a Master Plan. A project designed to aid the river in what it does, what it has been barred from doing naturally, by assembling and arranging pumps that would gather and disperse much needed sediment. A project that costs fifty billion dollars. It almost seems impossible.

But if we can build a wood box.

Sometimes us humans can do something right. The Bald Eagle: 417 in 1975, now 9,250 today. The Bison: 750 in 1905, now 350,000 today. The ozone layer, it’s actually healing. We have the capacity to be care-takers instead of destructors of our planet. We have the capacity to do more than serve our own self-interests.

It’s a nice thought.

We are floating on kayaks down the Shell Bank Bayou. We are making friends with Cypress and Tupelo, with shaggy, hanging Spanish moss, with white flowers called Arrowhead, with a black beetle and a green frog the size of the tip of my finger. We follow an egret for a while, or the egret follows us. We feel the sad, quiet beauty of growing to love something that will inevitably become lost. When we finish the trek, we pack up our kayaks and pick up some cigarette butts, plus an empty can of Vienna sausage that a careless fisherman must have forgotten.

Hey, I think to myself. It’s a start.

Elizabeth Miki Brina received an MFA in Creative Writing, concentration in Creative Nonfiction, from University of New Orleans. Her work has appeared in Hippocampus, Crab Fat, Hyphen, and New Delta Review, among others. She teaches at Xavier University and Bard Early College of New Orleans.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.