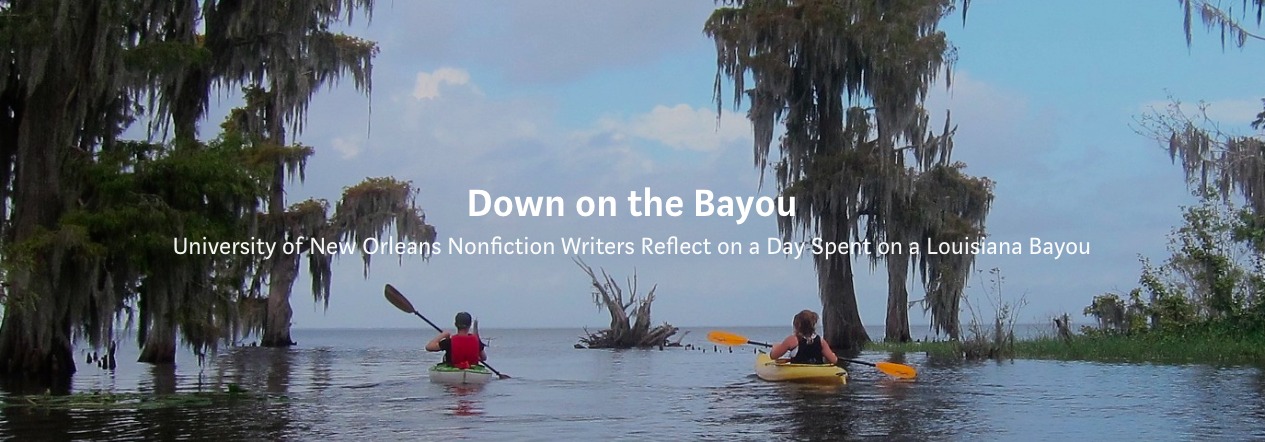

Students kayaking down the bayou for Richard Goodman’s MFA course. (Photo from: Down the Bayou website)

Editor’s Note: Caro Fautsch took part in Richard Goodman’s Master of Fine Arts nonfiction writing workshop at the University of New Orleans, where the students take a kayak trip down a southeastern Louisiana bayou in order to observe the issues and conditions that make the bayous beautiful and precarious. Once they finish their full-day kayaking adventure, the students reflect and write, creating pieces that encapsulate their experience and give new awareness about the bayous. ViaNolaVie will be running these pieces as a continued series every week, and you can also read more student writing here and here. And now for Caro Fautsch’s “The Gentle Light: On Poetry and the Bayou.”

Caro Fautsch, writer and student of MFA creative non-fiction workshop. (Photo: Caro Fautsch)

What I remember most is how bold the white-and silver-barked cypress trees looked in relief against the clear-blue sky. “A relic forest,” our guides said as my nonfiction class and I paddled by in our kayaks, and the word relic seemed so apt. The dead limbs of the white trees climbing upward with a kind of jagged elegance, the silvery Spanish moss twining downward to trail along the waterline.

With the tombstone color of the trees and the sky and the hushed air, the forest had the reverent feel of one of the New Orleans cemeteries on a sunny day. Even our banter had that familiarity. Strolling through a cemetery on a Sunday, joking and trading a flask — one of my New Orleans memories, now paired with this one.

I kept thinking, should I be finding such a terrible place so beautiful? Should I be having a good time?

Trying to parse it all out, a phrase from a poem by Adam Zagajewski came to mind: Try to praise the mutilated world.

Try to praise the mutilated world.

Remember June’s long days,

and wild strawberries, drops of rosé wine.

The nettles that methodically overgrow

the abandoned homesteads of exiles.

You must praise the mutilated world.

You watched the stylish yachts and ships;

one of them had a long trip ahead of it,

while salty oblivion awaited others.

You’ve seen the refugees going nowhere,

you’ve heard the executioners sing joyfully.

You should praise the mutilated world.

Remember the moments when we were together

in a white room and the curtain fluttered.

Return in thought to the concert where music flared.

You gathered acorns in the park in autumn

and leaves eddied over the earth’s scars.

Praise the mutilated world

and the gray feather a thrush lost,

and the gentle light that strays and vanishes

and returns.

This is not a complex poem, but it’s a poem full of imagery and movement: a montage of flickering scenes. Anchored by that shocking word mutilated. It is a collection of small, transient things (drops of wine, nettles, flaring music, acorns and leaves, the play of light, the fluttering curtain) paired with big, empty relic-spaces (the memory of June’s long days, the ship-graveyard, the nowhere of refugees, the earth’s scars). There is the evidence of violence, and there is the eerie peace afterward.

With a touch as gentle as the light invoked in the last line, the word mutilated becomes a marching-song. You must love all of it. Even the executioner sings joyfully. And in these wetlands we are the executioners.

As I kayaked along I couldn’t help but think, you’ve seen the stylish yachts and ships…

Earlier in the day, Bob Marshall, a Louisiana journalist, had lectured the class on the dire situation of the wetlands, but what stuck out to me even more than the finely articulated timeline of their destruction was the word he used to describe his relationship to the bayou: church. My church. As well as my livelihood.

What is it to love a church that is crumbling, to chart your life’s work on a map with disappearing points? Because the wetlands are lost at such a rate that the maps are out of date within a couple of years. A football field every forty-five minutes, was one of the heurisms. We keep losing names on the map. Eventually, sooner rather than later if we’re not wise, we’ll lose New Orleans.

This is not any kind of abstracted reality. The evidence for it is on the city’s sloped streets. To walk through New Orleans, to look at the levees, is to know that we’re already under the sea. (Living here, I barely see the Mississippi; the levee walls are high and the existence of the sinking city demands they get higher and higher.) Just as to kayak through the bayou is to know that the cypress is dying. Salty oblivion is almost here. So what is it to love this place, accept the devastation, and yet not settle for it?

I can’t speak for Bob Marshall, of course. But as someone newly living in New Orleans I want to be able to speak for myself. And in this as with many other matters, I think poetry can guide me.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.