Although Tulane University has its fair share of interesting art, I left campus one sunny Sunday afternoon and set out to find Dean Ruck’s Ourglass sculpture, located on Poydras Street between Loyola Avenue and Lasalle Street. Though I did know that Ourglass was part of the Poydras Corridor Sculpture Exhibition, I did not initially know the piece’s exact whereabouts.

My confusion resulted in a long walk down Poydras Street, frantically searching for Ruck’s work among a handful of other pieces. I took several approaches, from texting a special phone number associated with the Poydras Corridor, to typing “Ourglass” into Google Maps; both efforts proved unsuccessful. My odyssey lasted around twenty-six minutes, as I suddenly had the idea to pull up an image of the piece and identify the buildings surrounding it, thus leading me to the sculpture itself. Upon finally arriving at Ourglass, I immediately recognized the 14-foot-tall work of art constructed of circular mirrors, all carefully placed on a figure in the shape of an hourglass.

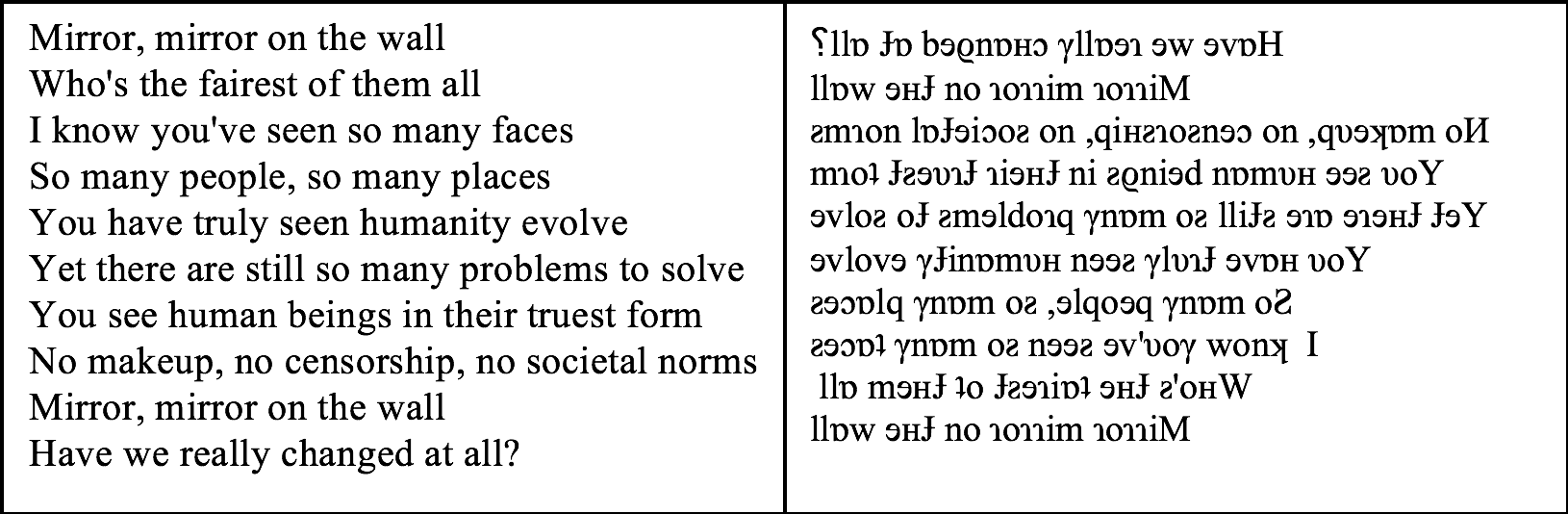

Ourglass (photo by: Talia Abed)

Employing mirrors for artistic purposes is no new feat — artists have been doing so since the third millennium B.C. Though mirrors were initially linked to representations of femininity and sex, the value of the mirror has evolved over time.[1] For example, many artists utilize mirrors in efforts to convey truth, seeing as mirrors hide nothing. Other projects, such as telescopes and microscopes, rely on physical reflection and thus utilize mirrors as well.[2] An artist’s use of mirrors in his work shows “his awareness of different levels of reality and varied functions of art as it records not only nature, but different ways of seeing”.[3] Often times artists will use the concept of reflection without using physical mirrors in their work. In France’s Chauvet Cave, 30,000-year-old paintings reveal creatures who seemingly divide into their own doppelgangers; the narrator of the film Cave of Forgotten Dreams comments on the fact that the image might simply be an imaginary mirror reflection.[4]

Ruck’s contribution to art pieces employing mirrors is a reflection of the times we live in. In today’s day and age, we are incredibly caught up in ourselves — whether it be the amount of time one spends using Snapchat filters or actively tracking the number of likes received on an Instagram selfie; our world is becoming increasingly more narcissistic. Ruck capitalizes on this idea by placing 500 mirrors on Ourglass.

People have always felt the need to communicate certain messages in specific ways, and this need is the motive behind most artwork. Artists using mirrors to convey these messages is indicative of the fact that mirrors are incredibly important to human beings. The concept of ego played—and still plays—a large role in the lives of every human around the world, and what better object to represent ego than a mirror? Egos have been the cause of wars, the foundations of successful businesses, and major contributors to someone’s self-confidence; a person’s ego is the sense of his or her personal identity, and this is exactly where mirrors come into play.

Artists call upon mirrors to deliver the message that we need to constantly be monitoring our egos, in both a positive and negative sense. People do not typically expect to see themselves in artwork, and to see yourself in a sculpture is to understand you are important enough to be part of the art, but a reminder that you are not the sole focus of the piece: everyone who comes across the sculpture is equally as important.

In addition to ego, Ourglass also encapsulates several other artistic meanings of the mirror. Though location is something every artist takes into consideration, Ourglass quite literally reflects its surroundings, thus making location—in addition to the concept of physical reflection—especially crucial to this piece.

Interestingly enough, the sculpture stands in front of the Hyatt Hotel, which I initially did not believe to be an accurate reflection of New Orleans culture. When I think of New Orleans, I don’t think of high-end hotels; I associate the city with colorful houses, Mardi Gras beads and street performers. I realized, however, that this placement is actually quite appropriate; hospitality and friendliness are two things I strongly connect with New Orleans and its natives, thus making the sculpture’s position in front of a hotel very fitting. On a more obvious note, the Superdome in the distance is seen in some of Ourglass’s top mirrors, and there is truly no better place to reflect New Orleans than the stadium where the Saints play. Despite the fact that the two institutions are used for entirely different functions, I realized the values represented in a hotel and the home of the Saints are eerily similar. Both buildings represent the concept of being part of something larger than oneself; the sole purpose of a hotel is to provide hospitality and comfort to others, and any New Orleanian knows that to love and support the Saints is to be part of one of the strongest communities in the world.

The physical sculpture of Ourglass is far from perfect, despite initial thoughts that Ruck had only chosen mirrors in mint condition. Rather, several of the mirrors contain severe browning on the edges, and a good number of them are cracked, as well — showing the viewer that society is not flawless, and the lens through which we see society is far from perfect; our egos often alter the way we view our surroundings. Yet, everything is relative; it shifts and morphs according to purpose, just like the sculpture itself. Whether it be due to the different faces that appear in front of it or changing colors in the sky, Ourglass never looks the same. Seeing as hourglasses are a representation of time, through this work of art Ruck conveys the idea that times are constantly changing, and it is up to us, those who stand in front of Ourglass, to adapt and thrive. This sense of collectiveness is reflected, both physically and literally, in the artist’s play on the word “hourglass.” The decision to name the piece Ourglass demonstrates Ruck’s thought process: the sculpture does not solely belong to him, but rather, to all the people (the “our”) choosing to admire it and who, consequently, become a part of it.

What makes “Ourglass” such an iconic work of public art is that the sculpture is audience interactive; upon approaching the piece, one becomes part of it, due to the nature of the mirrors. This emphasizes Ruck’s focus on community, as not only does the public have access to Ourglass, but they are physically part of it.

Sources:

[1] Alexander, Robert L. “THE MIRROR, TOOL OF THE ARTIST.” Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol. 4, no. 2/3, 1985, pp. 55–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23202427.

[2] Alexander, Robert L. “THE MIRROR, TOOL OF THE ARTIST.” Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol. 4, no. 2/3, 1985, pp. 55–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23202427.

[3] Alexander, Robert L. “THE MIRROR, TOOL OF THE ARTIST.” Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol. 4, no. 2/3, 1985, pp. 55–58. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23202427.

[4] “Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) Movie Script | SS.” Springfield! Springfield!, www.springfieldspringfield.co.uk/movie_script.php?movie=cave-of-forgotten-dreams.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.