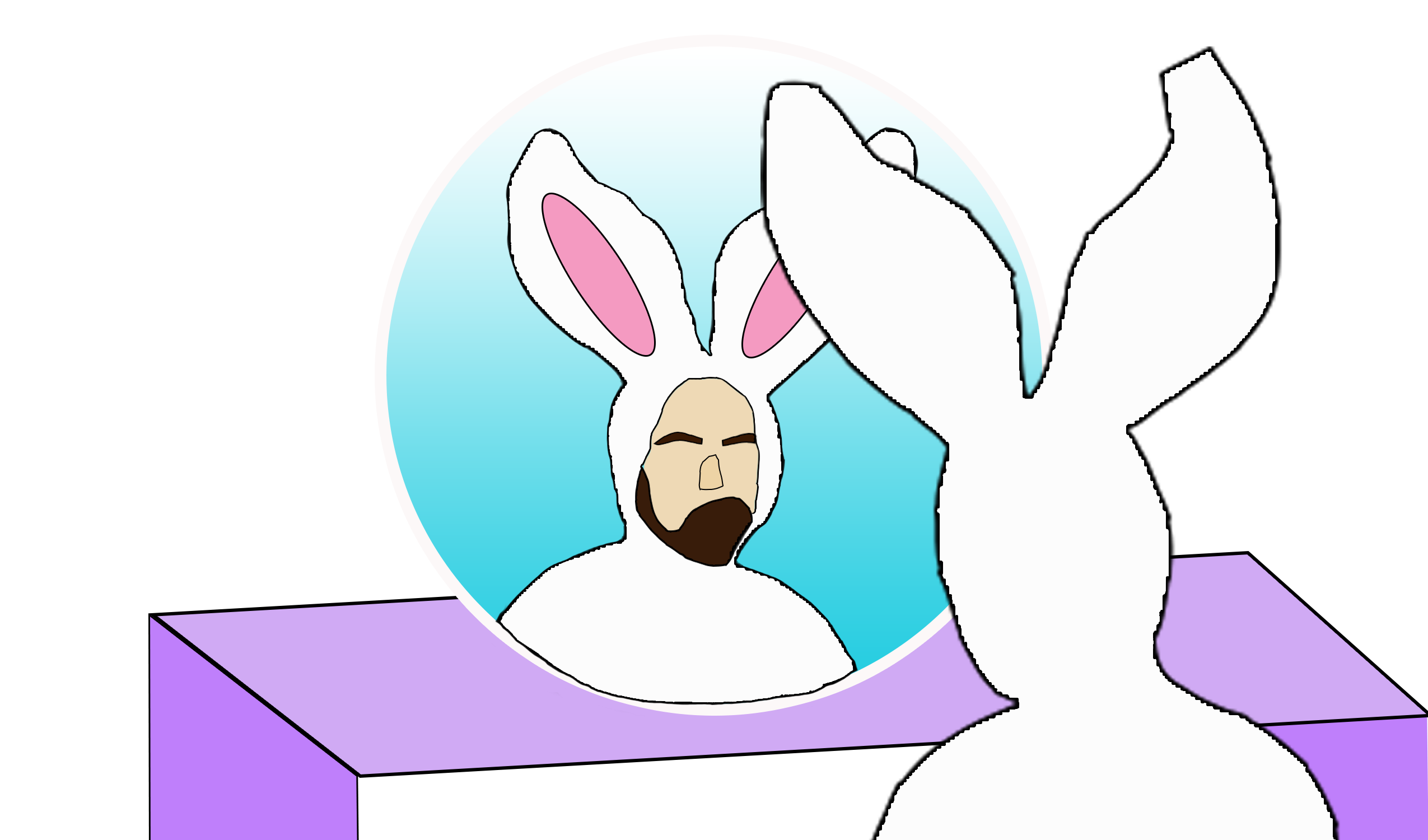

“Watching Podesta” (Drawing by: Jensen Foerster)

“These boys and toys and bunny/man chimera will be forever locked in the Sisyphean toil of misapplication, miscomprehension and misunderstanding.” – Alex Podesta

Through today’s overflow of social media, technology, and mass consumerism in our modern era, human communication may seem more connected than ever. However, taking a step back, over the past century it seems as though mass media has reconstructed and redefined how people communicate (now virtually, perhaps making human communication seem more distant than ever). Thousands of years ago, before the world of media evolved, humans used language and arts as forms of interpersonal communication. As portrayed in Werner Herzog’s award-winning 3D documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, wall art served as an ancient (and public) form of communication that allowed people to interact, converse, and ultimately feel for centuries (1). Herzog’s documentary explores the inner parts of southern France’s Chauvet Cave, and these ancient wall art pieces include sketches of horses, cave lions, and bears depicting the importance of animal symbols and their portrayal in public art. As art has progressed drastically due to the introduction of the digital age, animals have served as important characters, figures, and players in supporting and contributing to human life and art/other media.

Alex Podesta’s “City Watch” sculpture, his bunny-men perfect atop a building on Oretha Castle Haley. (Photo: Jensen Foerster)

New Orleans is a city that has become a booming art center over many years. Filled with a mix of vintage, modern, and alternative public art, the Big Easy’s community preserves and cherishes artistic voices and messages that must ultimately be recognized. One of the most interesting pieces of alternative public art is Alex Podesta’s City Watch sculptures. Perched atop a rooftop down on Oretha Haley Castle Boulevard in Central City New Orleans, five large bunny-man sculptures, made from plaster-molds of artist Alex Podesta’s own body parts, gaze over the street.

These self-portrait pieces by North Carolinian artist Alex Podesta, combine the visual of his own bearded face with the life-size body of a fluffy white bunny rabbit. Podesta, animating himself through the personification of a large, stuffed animal-like figure, incorporates his own self-being into these portraits, detaching his sculptures from the reality and seriousness of everyday life (conveying the ultimate importance and need for more public and local art displays).

Famous for many of his “bunny-man sculptures,” Podesta’s public sculptures and other works are captivatingly humorous and memorable. Podesta explains on his website, how his fantastical works, “…attempt to plumb the depths of the creative and comprehensive naiveté of youth; to illustrate, in engaging and serio-comic ways, the role of fantasy, ‘othering’ and conflict in nascent self-awareness.” Utilizing molds of his own face and body, Podesta alters and re-imagines himself through the magical and surreal image of a human-sized bunny rabbit.

Alex Podesta’s “City Watch” sculpture, his bunny-men perfect atop a building on Oretha Castle Haley. (Photo: Jensen Foerster)

As I ventured to see the roof bunny-men one sunny Saturday morning, I drove through a neighborhood where I saw old men smoking in wheelchairs, young people on bikes, and children playing basketball and hopscotch on the cracked concrete. Local people conversed on the streets in small groups, bathing in the weekend sun. Approaching the sculptures, I saw small bunny ears poking out from above a building’s roof. Bearded, emotionless, and manly, Podesta’s City Watch sculptures are quite a strange sight to see paired against a beautiful bright blue New Orleans sky. These Podesta bunny-men were made over a decade ago, and were then later moved to Oretha Haley Castle Boulevard to protect the streets that they stand over. The public monument’s strange placement and repetition of identical sculptures is questionable, however at the same time, makes a whole great deal of sense. Facing outwards, not looking at one another, they appear as guards protecting and watching over Central City.

Interestingly, Podesta’s City Watch title implies an overarching, patrolling-like quality that the bunny rabbits may possess while surveilling the surrounding streets. In this case, the bunnies could serve as a metaphor symbolic of people’s interactions with societal institutions and the inescapable “publicness” of today’s society, comparing Podesta’s sculptures to the monitoring systems and social groups that limit and diminish people’s privacy in everyday life. Similar to this theme, along Oretha Haley Castle Boulevard and the Central City streets nearby, are plenty of wired surveillance cameras to detect street local crime, theft, and potential traffic violations. Together, the visual dichotomy of the grey-wired, bulky surveillance cameras and the five pink and white bunnies proposes a clever, yet frightening commentary on how we are constantly being watched and surveyed by our peers and technologies.

On the other hand, Podesta’s bunnies could also be representative of the average passing pedestrian or New Orleans local, observing time and life go by them right before their eyes. Metaphorically speaking, Alex Podesta, like everyone else, even like his sculptures (and even an actual bunny), constantly observes and watches their daily surroundings, ultimately faceless and defenseless to life’s difficult realities, and these sculptures emulate and confront the feeling of this constant social anxiety everyone faces. As the seasons and New Orleans storms pass, although the paint on the bunnies begins to fade and chip, the sculptures remain, just like we humans do.

Through both perspectives, whether the Podesta bunnies are mocking us or are one of us, Podesta’s bunnies alter how we perceive our local surroundings and art itself. On the roof’s edge, high up and detached from the local streets, the bunny-men sculptures are able to escape from normal (everyday) images and perceptions of reality in an ambiguous, almost satirical way.

“Imagining Podesta” (Drawing by: Jensen Foerster)

It may be funny to think about it, or even to say out loud, but there really is something magical and mysterious about bunnies. Throughout history, books, film, television, and other media forms have depicted and portrayed bunny rabbits as representative symbols of childhood magic and imagination. The image of the rabbit has proven itself “…to be a catalytic object for dialectical questions of presence and absence, as well as metaphysical explorations of madness, sanity, and those existential forms of psychic liminality which lie between these relative poles” (2). For many people, their associations with bunnies are triggered by nostalgic moments of their own youth, reminiscent of famous childhood cartoon characters like Looney Tunes’ Bugs Bunny and the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, or even of childhood birthday party magicians. For others, bunnies could seem somewhat haunting or satanic as seen in famous films like Watership Down and the famous evil bunny Frank in Donnie Darko.

By evoking these youthful or fearful associations modern people make with rabbits and bunnies, Podesta successfully makes viewers communicate and interact with his rabbit sculptures. Although Podesta’s intent and message is not fully clear, perhaps that is his ultimate intent after all. Podesta states that his sculptures of “boys and toys and bunny/man chimera will be forever locked in the Sisyphean toil of misapplication, miscomprehension and misunderstanding.” Reminiscent of themes of identity, youth, and transformation, Podesta’s alternative bunny-men art pieces are supposed to confuse, distort, and mystify. So maybe it is not too funny to think about because maybe there most certainly is something magical about Podesta’s “City Watch” bunnies.

“Reflecting Podesta” (Drawing by: Jensen Foerster)

Sources:

This piece was written for Alternative Journalism, a class at Tulane University taught by Kelley Crawford.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.