By: C.W.Cannon

This story was reprinted with permission from The Lens, New Orleans area’s first nonprofit, nonpartisan public-interest newsroom, dedicated to unique investigative and explanatory journalism. The original story can be found here.

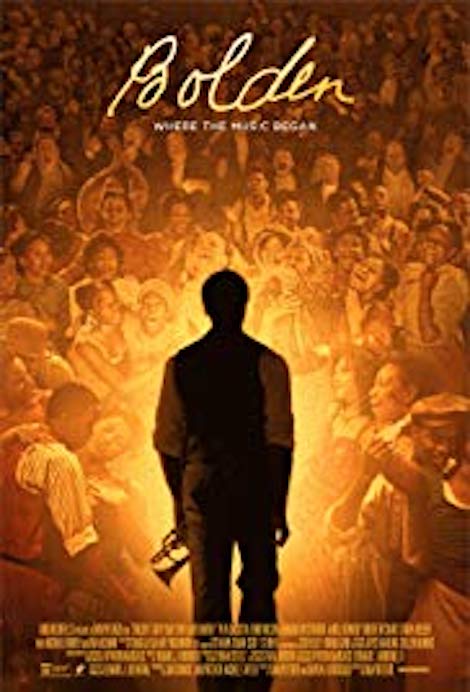

Directed by Daniel Pritzker, the new movie places the jazz pioneer in the firmament of New Orleans mythology..

In the American imagination, the myth of New Orleans serves as a repository of fears and desires America has about itself, especially concerning race, sexuality, and the possibilities and dangers of the aesthetic life.

The recently released Bolden, written and directed by Daniel Pritzker, is an instructive expression of that urge to mythologize New Orleans. It’s easy to find fault with the film, but at least it dares to dream, which is to say it dares to probe deep, uncomfortable psychic terrain rich in symbolic imagery.

An opposite impulse is the revulsion against the myth of New Orleans in any form, expressed perfectly in a much less ambitious effort, a Saturday Night Live skit that aired in January.

While Bolden is courageous (again, in spite of its faults), the SNL skit is a classic of middle-brow arrogance, an unselfconscious submission to the tyranny of mediocrity. It presents a couple of tourists just returned from New Orleans, who engage in some artful fantasizing about ways in which New Orleans differs from the rest of the United States: a looser attitude toward punctuality, an embrace of sensuality, and a voodoo ritual that appears to have been simply a mugging.

The guy is wearing a straw hat and, like his partner, feigns a pseudo-drawl intended to make fun of those poor souls who try to perform New Orleanian identity. They are, of course, roundly ridiculed by the other people on stage, including Kenan Thompson, the blandest guy there, who claims he’s really from New Orleans and knows that it’s no different than the rest of the U.S. The humor is supposed to hit its peak when he assures the dumb tourists that “New Orleans is in America!” It’s also significant that the arbiter of American conformity in the skit is African-American. SNL cultural policing will allow neither black people nor New Orleanians the luxury of self-definition. Both African-Americans and New Orleanians must instead forever loudly proclaim their 100 percent Americanism—or be shunned.

The mean-spirited little sketch is a shopworn iteration of a puritanical Americanist view: all fantasy, play, or performance is inauthentic fakery. So just try to look like a mid-price fashion catalog and avoid any kind of art or performance at all costs. Never leave Applebee’s and you’ll be safe. If you do happen to live in New Orleans, you can hang out in the new Marigny Starbucks and no one will call you a poseur.

Unlike the frightened herd animals at SNL, Pritzker’s Bolden has the guts to acknowledge and explore the myth of New Orleans in the American unconscious, despite a high risk of combustion. As an origin myth of New Orleans music, Bolden has much in common with previous movies purporting to depict the dawn of jazz, such as 1978’s French Quarter, 1947’s New Orleans, and 1941’s Birth of the Blues.

But there’s a welcome difference among them. Over the years, the agency of black people in creating their own culture has steadily grown in these filmic depictions. In Birth of the Blues, a white man (Bing Crosby) discovers jazz on a mythical Basin Street. Bolden has more in common with New Orleans, since both movies feature soundtracks by leading New Orleans jazz musicians of the day—Louis Armstrong in the 1947 film, and Wynton Marsalis in 2019.

In New Orleans, the musicians are black, at least at first: Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, and several other giants of the first half-century of jazz history. But they aren’t allowed to do anything more than play their instruments. The black characters in the 1947 movie are infantilized autistic savants who need white people to manage them, to take the music out of the dives, out of New Orleans, and eventually away from black people altogether.

The final cringe in a long line of them comes at the end of New Orleans, the movie. Jazz finally gets the recognition it deserves, but far away from New Orleans, the city, and with not a single black person performing. The triumph of jazz on the world stage is represented in the final scene by Woody Herman’s big band rendering a safely whitened-up “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans.” Thus the actual city is erased so that it can be “missed” by the people who claim to have once loved it.

Bolden, by contrast, puts black characters at the center, and gives them a black manager, but perhaps errs too much in the other direction by presenting jazz as something no white musicians need even try to play. And the black manager is, of course, an evil figure, an entrepreneurial parasite who sells out black people in exchange for a modicum of power conferred by whites.

The extent to which these movies “get it right” factually is a good question, but not the central one. The central question is what psychic process Americans are going through as they tap into that space in the American unconscious called New Orleans.

It goes without saying that the real New Orleans will have to undergo some simplification and misrepresentation as Americans process what it means to them on an emotional level. One result is an inevitable Americanization of the material, to make it something national audiences can understand. We see this Americanization of our local social and cultural history at work in every movie set in New Orleans, not just the ones about jazz.

The first step in the process of aesthetic Americanization is bad news for those New Orleanians who like to emphasize how the city has distinguished itself from the broader region. In myriad ways, New Orleans’ history in the American mind is flattened into Southern history. New Orleans society is almost always presented as not significantly different from Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, etc.

One way this is accomplished is by erasing the French presence. We saw it in American Horror Story: Coven when Kathy Bates’ French-speaking Madame LaLaurie was depicted speaking English with a standard Hollywood version of a Southern accent.

The language and cultural divides of Creole New Orleans are especially confusing to Americans as they relate to black people. Though French-speaking gens de couleur libres of antebellum New Orleans were a subject of fascination to 19-century writers, Hollywood has been unable to acknowledge their existence in any antebellum costume drama set in the city, no matter if it’s the white supremacist Hollywood of William Wyler’s Jezebel (1938) or the ostensibly anti-racist statement of Richard Fleischer’s Mandingo (1975).

In Bolden, the Afro-Creole/African-American divide is vaguely alluded to but reduced to simple colorism. The film refers to Afro-Creoles as “blue-eyed n—–s” and “light-skinned n—–s” but never as “French” blacks or, dare we suggest, “Creoles.” They even anglicize the pronunciation of Afro-Creole clarinetist George Baquet’s name, calling him “Backette.”

The reductive flattening of New Orleans’ historic linguistic and ethnic complexity into the generically “Southern” white/black dichotomy is common to almost all movies set in the city, but origin myths of New Orleans music have their own special mythical calculus, dating from early 20th-century social conditions and American fears and desires stemming from them. I call that bundle of anxieties and yearnings the “Storyville Complex;” it hinges on a fairly simple equation: race+sex=crime+music.

Historian Shannon Lee Dawdy has written about how the earliest myths of New Orleans were rooted in fears of social disorder. The Storyville Complex is no exception. In her book Building the Devil’s Empire, Dawdy lists several definitions of disorder from an 18th -century French dictionary, including a “disarray of rank or organization,” “moral” disorder,” and, finally, “un beau désordre”—beautiful disorder, disorder as an aesthetic category.

Though Dawdy was writing about colonial New Orleans, the different registers of the meaning of “disorder” also basically explain the Storyville Complex. Race+sex (interracial sex) is a “disarray” of social rank, a disruption of the racial order, and can be seen as the original sin of America’s original “Sin City.”

The understanding of interracial sex as an unforgivable sin has not changed, though 19th-century white supremacist Americans and latter-day anti-racist Americans deplore it for ostensibly different reasons. The onus has shifted from the unscrupulous octoroon temptresses described by Grace King in “New Orleans: the Place and the People” (1895) to the white-supremacist prerogative of owning and violating black women’s bodies. But puritanical Americans continue to struggle inordinately with the notion of consensual interracial sex.

As several well-researched studies have shown, notably Alecia P. Long’s, interracial sex was the crux of both the attraction and opprobrium of the vice district known as Storyville in the first decades of 20th-century New Orleans, an era that coincides with the formation of early jazz. But most films about the era have had great difficulty with the race+sex side of the equation. Dennis Kane’s 1978 French Quarter, for example, gives a prominent role to Countess Willie Piazza—but makes her white.

Just as free people of color remain invisible in the popular American imagination of the antebellum era, the iconic black madams of Storyville—Willie Piazza, Lulu White, Emma Johnson—have proven too explosive for Hollywood in any era. Bolden touches on the race+sex angle only peripherally, if we limit the equation to explicit reference to sex between white and black. Its richly symbolic imagery does invoke, however, the trope of the “octoroon cyprien,” to borrow Lafcadio Hearn’s term for a mixed-race New Orleans temptress.

Bolden features an unnamed, unscripted, beautiful Afro-Creole woman who fulfills her usual symbolic function: Afro-Creole femininity as a prize that white and black men fight over. In earlier scenes, we see Bolden longing for her as some kind of unattainable goddess, playing a cello. His longing for her coincides with the beginnings of his demise. Thus, however unconsciously, the movie does invoke the classic trope of the mixed-race Afro-Creole woman as disrupter of the social order, in this case as a siren for black men rather than white.

In a wordless later scene, we see the same actress by the side of the white devil of the movie, a judge named “Leander Perry” (an obvious reference to the white supremacist political boss of Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes, Leander Perez, who died in 1969). It eventually becomes clear that this mysterious, beautiful woman is Buddy Bolden’s muse. After the white devil destroys Bolden’s only recording, we see her naked, mutilated body on the floor.

That image crystallizes the way the movie plays on the Storyville Complex, even while dodging the uncomfortable issue of interracial sex. Black sexuality in the movie is as much a visual subject as is black musicianship—scenes of black people having sex are almost as common as scenes of black people playing music. Thus a linkage is made between black sexuality, black music, and the hopelessly corrupt world the story takes place in, the crucible of moral disorder that gives rise to the beautiful disorder that strikes the ears of the early jazz listener.

The term “crime” in the Storyville Complex equation needs to be understood more broadly as corruption on three levels: political (including police), spiritual (moral) and also physical. The high incidence of disease in 19th-century New Orleans was the perfect sign to puritanical America that race mixing, a moral crime in their eyes, resulted in physical corruption as well.

As advances in medicine and public health curbed the raging outbreaks of yellow fever, cholera, and other killers, drug addiction took their place in America’s imagination of New Orleans as a cancer on the national morality.

Bolden dutifully fulfills that expectation and adds to it the post-Civil Rights era understanding of the primal source of the corruption infecting every aspect of life in mythical New Orleans: not African savagery, the bogeyman of the white supremacist era (when voodoo was routinely described as “devil worship”), but the savagery of white supremacy itself. The Prince of Darkness in Bolden is the white judge, and he’s the one who passes on to his black lesser demon (Bolden’s manager) an unnamed white powder that begins to lay waste to the black community.

Locating the source of New Orleans evil in white supremacy rather than in race-mixing or in people of African descent is an improvement over earlier iterations of the myth of New Orleans corruption, to be sure, but it poses a new set of problems.

The most glaring of these is that New Orleans—when presented as the paragon of Southern racial injustice—serves as a scapegoat for a failing that afflicts the entire nation. When white Northern liberals like Pritzker, director of Bolden, or Richard Fleischer, director of Mandingo, or Arthur Lubin, director of New Orleans, project white America’s fears and fantasies about race onto New Orleans, their films flirt with implying that the rest of the country is somehow absolved.

Of course it also hurts my feelings that every white New Orleanian in ‘Bolden’ is an N-word spewing cracker stereotype with a Mississippi accent. On the other hand, we can’t pretend that Bolden’s New Orleans was not a viciously racist society, and it’s probably good that the kumbaya version of early jazz, familiar to devotees of Jazzfest’s Economy Hall Tent, gets shaken up from time to time.

A deeper problem for New Orleans mythology is suggested by the most insightful line of the movie, though it seems to be discredited by the speaker, the white devil Judge Perry: “Hate your oppressors and you’ll be enslaved forever by your memories.” This points to an intractable paradox identified a hundred years ago by W.E.B. DuBois in The Souls of Black Folk, the psychic impossibility of an identity defined as a social “problem.” If your whole existence is a problem, nothing is untainted. Can the “beautiful disorder” of inspired art ever be separated from its roots in barbarism and appreciated for its own sake? Should we even try?

C.W. Cannon

Such questions lead to an impossible further question: if New Orleans is to be the repository of America’s dark and guilt-ridden fears about race, how can it ever be anything other than a nightmare? Pritzker’s signal accomplishment with Bolden is to present the dawn of jazz as a nightmare that somehow, inexplicably, is also beautiful.

C.W.Cannon teaches “New Orleans as Myth and Performance” at Loyola University. His latest novel, Sleepytime Down South, is also rooted in jazz mythology.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.