Editor’s note: Tulane environmental studies and public health major Gabriella Burns recently visited three New Orleans hazardous waste sites with Wilma Subra, owner of environmental consulting company Subra Inc. and a MacArthur Genius Award winner for her work in environmental justice issues along Cancer Alley. This is the first of a three-part series on what she found.

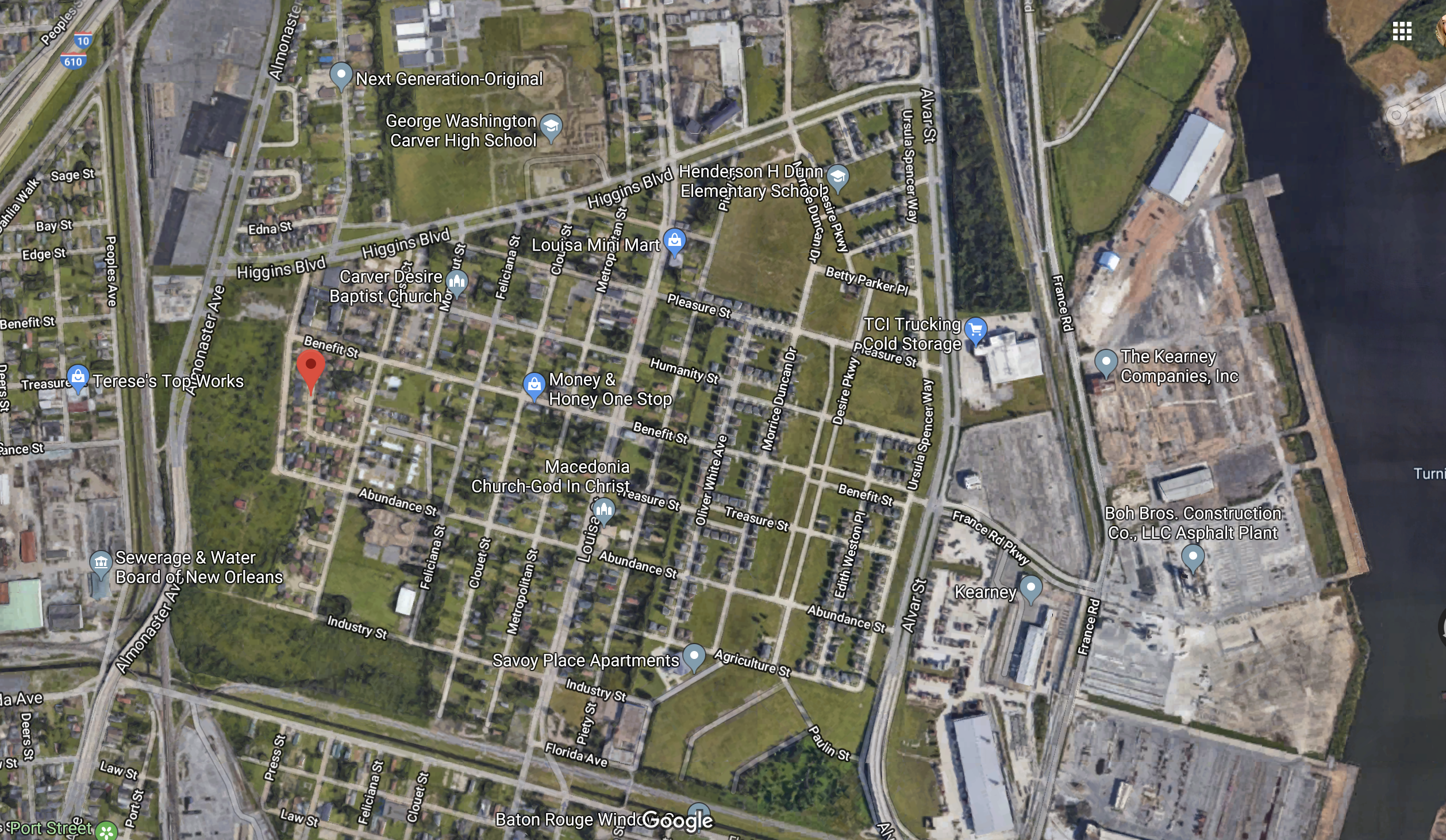

Gordon Plaza (Photo: Google Maps)

Gordon Plaza is a small community tucked away between I-10, an industrial canal, and a few industrial plants along the Turning Basin. These people have fought for more than 30 years to be relocated from their homes on top of the former Agriculture Street Landfill. Their houses were originally constructed in the 1980s by the City of New Orleans and were marketed as an affordable option for African Americans to become homeowners.

Issues with the landfill are not merely recent; they’ve plagued the land since its inception in 1909. Agriculture Street landfill earned the nickname “Dante’s Inferno” during its time as New Orleans’ main landfill because it caught fire so often. The burning did not stop after it was closed in 1952.

“When Hurricane Betsy came [in 1965] and destroyed this area, the landfill was reopened again, to accept the waste from Hurricane Betsy,” Subra explains. “To reduce that waste, there was a lot of open burning on the landfill site.”

The landfill’s role as the main waste disposal site for residential, commercial, and industrial waste, coupled with the frequent fires there, led to the land’s contamination with 151 different toxins.

Despite the city’s knowledge of the site’s history, the administration chose to turn the former landfill into a residential area. In the 1980s, 67 individual homes were sold to first-time home owners. Buyers were not informed that their new homes sat on a former landfill, Subra said.

“Some indicate that they actually said, your lot and your house have been built on top of [a] fill. Well, anyone who looks in New Orleans for a house, they want to be sure there’s something under the house to protect it from subsidence. And so people thought it was just fill material. They had no idea it was a landfill with municipal and industrial waste.”

Oblivious to dangers beneath the newly constructed neighborhood, buyers flocked to the new development.

“It was an opportunity to really move up,” Subra said, adding that a major lure was the neighborhood’s many amenities.

“Moton elementary school was one of the attractions. You could have a house here, you could send your children to elementary school here, there was a shopping center as well, you had everything you needed right in this area.”

Everything changed when excess lead levels were detected in water from a sewage line break at the community’s elementary school in the early ‘90s. Seeing the number of hazardous chemicals found at rates astronomically higher than the EPA allows was a rude awakening for people who thought they were buying into the American dream. The EPA named it a Superfund site and promised to remediate the area, but the result was not sufficient in residents’ opinion, says Subra. (For more information on Superfund sites, click here.)

“They removed and replaced 2 feet of soil. They put on an impermeable layer, then they put what’s called construction fencing, that orange fencing you see if you go buy a construction site, and then they put two feet of clean soil.”

This remediation occurred on only 10 percent of the developed area of the former landfill. The undeveloped area had a slightly different protocol.

“On the undeveloped area, they just graded it down, then they put that permeable layer, and then they put the construction pins, but they only removed 1 foot. The agreement with the city was that they would cut the grass on that undeveloped every quarter or twice a year to make sure that no trees grew, because the tree roots would have gone in and messed up that line. The city never did follow through on what they needed to do. And all you have to do is look and see, there are lots of big bushes and trees, all those roots are going right through the liner and the tree.”

The undeveloped land is fenced off so that nobody can access it. However, water from flooding, particularly during frequent New Orleans rainfall, can cause hazardous particles to rise up through the soil and onto the surface.The fencing might be able to stop people, but water passes easily through its chain links.

Subra revisited the Agriculture Street Landfill after Hurricane Katrina because she was concerned about the potential health impacts of the contaminated floodwaters.

“Hurricane Katrina came and it flooded this whole area, it wind damaged this whole area, and then they had a sediment sludge tidal surge that came in here and brought you huge amounts of contaminated heavy metals, polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, everything people had dumped in a water body for decades and decades and decades,” Subra said.

Not only was the area contaminated after the hurricane, but returning residents could not access federal funding for reconstruction because it is illegal to use those funds on a Superfund site. Rent-to-own townhomes lay vacant for years, until city officials had them torn down a few months ago, complete with their former residents’ belongings from years ago.

Most of the other people who live in Gordon Plaza returned. Many had no choice. Due to their location on a Superfund Site, property values on their homes are significantly lower than when they purchased them. Selling their homes would not make enough money to buy a new one.

Ultimately, the residents of Gordon Plaza have lived on a toxic landfill for more than 30 years now. They don’t know all the repercussions of living on a former toxic landfill. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry has determined that breast cancer rates are significantly higher in the area.

Subra says that, in the end, it comes down to politics. Nobody wants to claim responsibility, so the issue continues to be passed down from administration to administration, through the decades.

Next Tuesday: Burns and Subra visit Thompson Hayward, where a playground is built atop a former Agent Orange factory.

Gabriella Burns’ articles are derived from a service learning project in Dr. Christopher Oliver’s course EVST 4410 Senior Seminar in Environmental Studies at Tulane University. This work is also part of a long-term project facilitated by the Critical Visualization Media Lab (CVML), led by Dr. Oliver. Dr. Oliver is Professor of Practice in the Department of Sociology and Environmental Studies Program. He is also Jill H. and Avram A. Glazer Professor of Social Entrepreneurship through the Phillis M. Taylor Center for Social Innovation and Design Thinking and a faculty fellow in the Mellon Graduate Program in Community Engaged Scholarship.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] end-of-century soil tests would confirm the presence of 151 contaminants in the soil, leached from the dump’s contents. Soil investigations are hardly […]