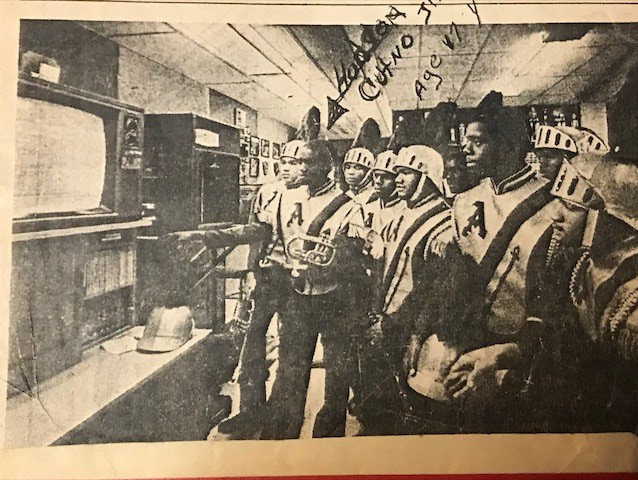

Why we ask, “What school did you go to?” (Photo courtesy of: Krewe Magazine)

“What’s the name of your school?!” a popular line in Dj Jubilee’s song “Get it Ready,” a New Orleans anthem played at almost every event hosted by an African American. Where you attend high school can determine how well you make it in New Orleans as well as in the world. The high school you attend in New Orleans is like a proud badge on your chest. The New Orleans high school experience is different, but the education is not up to par with the rest of the country. Louisiana schools alone ranked as #49 in America rated by the U.S. News. The New Orleans racial demographic is predominantly African American, and many students aren’t provided with the rigorous opportunities to get them beyond high school into the real world.

“One word I’d use to describe the experience of an African American student in the education system is complex. I say complex because even if you are a black student at a school that’s high performing there is still going to be challenges that you face because of your race,” says Tiffany Lewis. “Black kids are more likely to be suspended, less likely recommended for gifted, their teachers may have biases or probably have biases and prejudices they aren’t even aware of.”

Ms. Lewis is an English II and World Literature Teacher at Benjamin Franklin High School in Gentilly, New Orleans. Benjamin Franklin High School is recognized as one of the top schools in Louisiana, but also as a top-100 school in U.S. News’ yearly report in 2018. According to the New Orleans Equity Index, the demographic breakdown of Benjamin Franklin High School in the 2017-2018 school year was 37% white, 30% black, 6% Hispanic, and 27% other. Franklin’s demographic breakdown is unique to the city of New Orleans because of its high white population of students, while the city’s average only being 8.7% white in most public schools. Benjamin Franklin’s selective admissions require students to test in to be accepted. This also separates Franklin from most public schools in New Orleans that use the process of the OneApp lottery because most students must apply to before attending their selected school.

“It’s not fortunate, and it’s not fair but the OneApp isn’t the issue. The issue is the lack of qualities schools, so you know most people, especially middle-class people, feel like either there are only certain schools their kids can go to or else they go to private school. I think the problem with whatever you use is the fact that there are only so many schools where kids can get a quality education,” says Tiffany.

New Orleans as of 2018 became the first city in the United States to become fully charter, and have no schools run under the public-school board of the city. For some residents in New Orleans, this move to completely “charter” is seen as progressive, but others see it as digression to improve the school system.

“I feel like if I was an average student, I might not have gotten the education just because I don’t think it’s a product of Karr itself. I think it’s a product of the New Orleans Charter school system, and just how they push test scores over education. So, I think it’s because of how I went about it personally that I made the most out of it, but overall, Nah. I don’t think people get the best education in New Orleans schools in general” says Korey Finnie, a 2016 graduate from Edna Karr High School. Finnie believes that his drive and determination for better is the reason he was able to succeed and attend Tulane University in the fall of 2016 on a POSSE Scholarship.

Edna Karr is ranked as one of the better high schools in the New Orleans area with 97% of students being African American. Finnie believes that most schools’ issues have to do with their yearning to receive funds. He also believes that most students have testing anxieties because of the push of EOC (End of Course) and standardized testing.

“I had interviews with the news, I had a meeting with Ellen! I had a video interview with Ellen trying to receive money for Karr. I was in a lot of promotional videos for New Orleans Education in general. I had all three principals’ numbers, and they would text me to do this event, and I could miss class.” Finnie describes his experience as very new for him and exciting. “If you weren’t excelling like myself, you were not thought about for those opportunities.”

Finnie says that during his experience at Karr the majority of the student body wasn’t aware of all the opportunities he was receiving from the school and the promotion of scholarships that were being thrown his way from school counselors and administration.

“It’s hard to be classified as a good student at Karr. Karr is known for football and that’s it. Karr has a lot of smart kids,” says Finnie.

After graduation, Finnie says he continued to try and push some of the opportunities he received to other students at Karr like the POSSE scholarship. Finnie also felt like while attending Karr there was a negative feedback trauma to the violent realities that face many youths in New Orleans to this day.

“I think that walking through metal detectors, being pat down, people checking your bags. You know what kind of vibe it is and whether that’s the case or not that’s the message being sent,” he said.

Finnie believes that school should be a release from the everyday trauma from the streets of New Orleans and that wasn’t the case at Edna Karr. He felt like having the security guards and metal detectors only made the kids feel more and more like street kids.

“I think trauma is normal in New Orleans schools. It’s a cyclical effect on you. We have people that live in these environments and they lose people every year and there is nowhere to go that truly tells them this isn’t normal.”

Despite these issues, Finnie says he wouldn’t have wanted to attend anywhere else for high school in New Orleans.

“I really wanted to go to John Curtis. We were a big family though going to Algier and seeing everybody. Going to Nomtoc and seeing everybody.”

Many middle-class African American parents resent the New Orleans public schools and send their kids to private and Catholic schools such as St. Augustine High School, St. Mary’s Academy, or Katherine Drexel Preparatory that cater to African American students in the city.

“The school [St. Aug] was created in the 1950s for African American males who weren’t allowed to go the traditional Holy Crosses, the Jesuits high schools in the city. The African American community possessed the need, the desire they wanted to have a school of its own. So, the original mission was to allow African American males to go to a school that would nurture both their spiritual, if you’re Catholic, and your personal development. So, St. Aug definitely had a big impact on my development,” says Hudson Cutno Jr., St. Augustine graduate class of 1986.

1950s New Orleans was a racial war ground, and the integration of schools was a major issue in the city. Catholic schools, such as Jesuit did not start integration until the 1962 school year, and even then there was still limited minority students admitted. St. Augustine High School created an environment for young men that the city had never imagined. The boys were required to wear business attire to school, including a necktie, which became their “unofficial” uniform until 1986. Today, the boys are still not allowed to wear jeans or tennis shoes to school. The professional dress that the school required of the boys continued to create a unique look for St. Augustine High School. The school created professionalism that continues to stick with many of the students.

“I enjoyed wearing a suit. It got you out of the routine mundane everyday street clothes. Sometimes I snuck my dad’s good shoes out when he went to work, and I’d wear them. After school I would hurry up and clean them before he got home” says Cutno. “It was just a totally different feeling.”

Cutno describes his experience at St. Augustine as “one of a kind.” Cutno says, “I attended co-ed school from pre-k through 8th grade. The experience at St. Augustine was different because of the competition, the camaraderie, the friendships that I made, it was just a totally different atmosphere. We have alumni that are 60 and 70 years old and they’re still talking about St. Augustine like they were actually at St. Augustine last year. I think the weight it holds in the city of New Orleans is because St. Augustine has the highest number of Presidential scholars in the city, the notoriety, the pride, the determination, and leadership that a large number of the graduates have instilled in the city is very noticeable,” Cutno says. “2600 A.P. Tureaud is the castle. It’s the address that I know. Before it was London Ave. When I hear that I know what my roots are.”

St. Augustine High School created a road map for success that some didn’t have at home. It allowed for boys to be taught by men that looked just like them. Cutno says he remembers many of his teachers were people who just recently graduated from St. Augustine five or six years prior to him.

“I was around other men and it allowed me to see what a man is supposed to be like, how a man should react, and how to talk. They were close to my age, so it gave me an idea and well pretty much a road map of what a man of color was supposed to be like.”

“A solution is community involvement. Particularly the schools that were the top performing black schools before Katrina. McMain, Easton, 35. I think the alum, myself included, have a responsibility to engage or re-engage with those schools,” says Lewis, mentioning her dissatisfaction with the push for Teach For America in New Orleans schools for its lack of cultural competence within the teachers. “Most of them are white middle class or upper-class background, most of them aren’t from New Orleans and I don’t think that they necessarily learn or are taught about the community they’re serving. They don’t know the children, and they don’t make any account to.” She describes the teachers from Teach For America as having a positive aspect because they bring in teachers due to teacher shortages in the area, but “your 1st year as a teacher you know nothing, so not only are you inexperienced, but you’re also in a different world.”

Finnie also mentions that a school’s success shouldn’t just be based simply on test scores, but also student experience. He remembers having days where students had the option to buy a hot plate of food or being given a cold meat sandwich. “That just isn’t right. What about the students who couldn’t have afforded the hot food that day. Was that really what they’re stuck with?”

“I don’t think the issue is charter v centralized school system’s you know? People like to blame it on charter’s, and I don’t think that problem is necessarily charter because there are some good things about the charter school movement. I think the public-school system is flawed. Whether charter or not charter. I think the school system landscape is flawed structurally,” says Lewis.

According to Nola.com, in 2018 about “40% of all students are held back at least once.” Students, parents, teachers, and administrations in New Orleans all hope for the best with the completely charter switch. Education is the key to opening doors for oneself and New Orleans public schools have lacked with providing these opportunities to many youths.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.