Anthropocene. It’s a mouthful, but it can be a useful rubric for conceptualizing the accelerating planetary changes happening from human impact. Not surprisingly, the main feature of the New Orleans landscape (itself is a product of human intervention) has become a touchstone for the Anthropocene: the Mississippi River.

To call the Mississippi an “Anthropocene” River is to acknowledge its co-relational production with people. It may have been etched from the buckling continent and expanding glaciers of the American high lands, but it’s also impacted by intensive efforts to maintain its water inside levees. In the most basic terms, the Mississippi long ago left its “natural” course and has, for at least three centuries since the arrival of the settler colonialists, been in a state of response to wide-scale interventions set upon it.

For this reason, the river for the last year has been the object of study for an initiative, called “Mississippi: An Anthropocene River” that is organized by HKW (Haus der Kulturen der Welt) and Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. The initiative, which includes a number of U.S. universities and institutions, culminates at Tulane in November for a week-long conference entitled, Anthropocene River Campus: The Human Delta.

From Nov 9-17, dozens of artists, activists and scholars will undertake a deep, interdisciplinary dive into the Mississippi through field trips, seminars and public events hosted by The New Orleans Center for the Gulf South. Together we will explore, perform, and critique the many ways the “Father of Waters” (Randolph 2018) has organized, impacted, and reflected the planetary ecology of our changing modern world.

I study the Mississippi’s role in producing the muddy ground upon which New Orleanians walk, celebrate, and even conduct their research. I’m also teaching a class this semester called, Life and Culture on the Mississippi River, which directly engages with the many lives of the Mississippi: as a producer of culture, an environmental phenomenon, a threat, a site of injustice, and a sovereign body with potential rights.

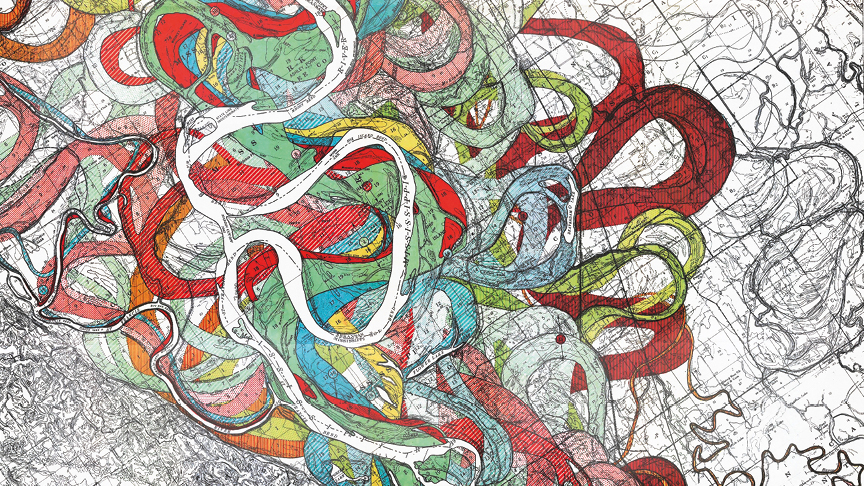

Hand-drawn maps of the Mississippi River meander paths made by LSU Geographer Harold Fisk in 1944 for the Army Corps of Engineers.

All of these perspectives fit into the concept of the Anthropocene, which has become the shorthand for describing what some call a new geological epoch initiated by the unmitigated advancement of mono-agricultural development, deforestation, global capitalism, material waste in oceans and landfills, and fossil fuel emissions.

While the tag, “Anthropocene,” is to acknowledge this co-relational production, the term itself is mired in academic debates about whether it naturalizes and attributes specific systems of brute colonial capitalism to all of mankind. The forces that hold the river in place are bound up in a particular legacy of plantation capitalism, which helped to drive levees and swamp reclamation programs that were forced upon black bodies for the benefit of white landowners. Indigenous peoples were meanwhile exiled from the basin because of American expansion. So to implicate all people with the tag, Anthropocene, is not quite accurate, or fair. Some have argued for the more precise, and differentiating descriptor of Plantationocene (Haraway 2015).

The conference taking place at Tulane will participate and trouble some of these conversations – which will inevitably cross disciplines. To hold up and discuss the complex layers of the Mississippi River and our relationship to it requires literacy in multiple disciplines and theoretical traditions – which is why the Anthropocene can be a helpful rubric.

In a recent podcast interview, organizers of the river initiative described the Mississippi as a touchstone for this new epoch with its multiple timescales, geographies, and cultural registers. The handling of the river invokes existential questions about the impact of settler colonialism on the long-term habitation of peoples and biomes that have been wiped out in the “blink of a geological eye.” The river – which includes its vast watershed covering 41 percent of the North American continent – is not only a site of competing interests and industries, but organizers hope, it can become an intellectual canvas for imagining new ways of living. A representative site of intellectual exchange, its material watershed also offers topographical demarcations for organizing spaces and practices.

The subject matter surrounding the river taps into my own fascination that started as an undergrad at Tulane with the essay, “Atchafalaya,” by John McPhee (McPhee 1989) that brings to life the impossible mandate of maintaining the confluence of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers at Old River Control, north of Baton Rouge.

My interest was heightened with Rising Tide (Barry 1997), which I read as a speechwriter to Marc Morial, about the great Mississippi floods of 1927 and the decision by the New Orleans elites to needlessly dynamite the levee south of the city in St. Bernard Parish. We witnessed the eerie parallels of a near repeat catastrophe this past summer as Hurricane Barry skirted New Orleans during what was the longest continual flood stage ever recorded on the Mississippi (Grabar, 2019).

I recall my shock when I climbed the levee in July at the Ninth Ward and Industrial Canal to see it lapping the riprap concrete just below my feet instead of its usual presence down by the batture forest. I imagine the same vulnerability was shared by the worried residents during the flood of 1927, or floods of 1922, or 1912, or 1884, or 1850, and so on…

“There is no sight like the rising Mississippi,” Barry writes. “One cannot look at it without awe, or watch it rise and press against the levees without fear…its current roils more, flow swifter, pummel its banks harder. When a section of riverbank caves into the river, acres of land at a time collapse, snapping trees with the great cracking sounds of heavy artillery. On the water, the sound carries for miles.” (Barry 1997)

Despite its surprising height last summer, river commerce flowed unabated as tanker after tanker swung that hairpin turn at Algiers Point sliding sideways towards the French Quarter wharves as if they were driving 18-wheelers on ice. Besides the few people fishing along the levee riprap and a school of ducks on the current, there was little of what one normally perceives as the natural world in its watery industrial corridor here at New Orleans. But the Mississippi experiences a world of changes as it flows through contested lands and histories.

The coming event in November will explore the very question of natural as it relates to the river. The legacy of interventions – which in many ways de-naturalize what was once called the “villainous” river (Twain 1883) – consists of levees, jetties, meander cuts, spillways as well as encroachment of permanent cities, agricultural erosion and chemical dumping. In that respect, to call the Mississippi a “river” is more of an existential exercise. What is a river that has been altered, straightened, squeezed, or even moved? A historian of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Todd Shallat, describes the Mississippi as a mud scape in motion “curling and coiling like a snake in a sandbox” bleeding soil from 31 states (Shallat 2006). It seems everyone has something to say about the Mississippi. Why not? Its legacy is interwoven through attempts to live, build and then protect those settlements alongside it. The effects of those decisions we continue to experience, if not accelerate.

A tagcloud of student answers to the question: What is a river?

This trajectory of change also raises very real questions about the ability to maintain the river at Old River Control to prevent its tendency to jump channels into the Atchafalaya, which also implicates any kind of viability for New Orleans.

The folks at HKW have organized a number of field stations up along the river that highlight the geographies and societies the river separates and connects. Part of this project’s aim is to engage the river at specific points while thinking in a planetary way.

In my environmental communication class, I’m asking students to trace the contours of this complex creature, the culture it has produced and the economy it has generated. As we discursively follow the river, we are engaging with the underlying tensions it calls forth between ecological sustainability and the tireless efforts to uphold it as an economic corridor. My students will engage in one of five Field Stations that have been happening upriver over the last year. Each field station has been conducting interdisciplinary research to “read” the Mississippi through various disciplinary questions: through water physics, agriculture, settler colonialism, extraction, commercial trade, and ecological flows.

These field stations have been producing work for some time now, but they are being activated through planned events to interact with a floating classroom of River Journey students, artists and activists paddling down the river to New Orleans. My students will be thinking about their connection to a particular field station’s work from their proximity here in New Orleans.

Field station 1: Settlement, Sediment, and Sentiment.

– Focuses on river lands between the headwaters at Lake Itasca, which is rocky and hilly, down to the flat, ‘unglaciated’ region known as the “Driftless” area that touches southeastern Minnesota, southwestern Wisconsin, and northeastern Iowa. This land is described as a tapestry of native lands, state parks and urban areas marked by lakes, marshes, streams, and rivers. Here, the Dakota, Ojibwe, and other native peoples contend with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ mandate to manage the river. Corps dredgers maintain a 9-foot deep navigation channel, and a total of 29 locks and dams enable commercial shipping. One of the questions field station researchers are considering is a deindustrialized future for this area and the difference between “sustainability” and “regeneration” through an indigenous viewpoint.

Field Station 2: Anthropocene Drift

– This Midwestern stretch is replete with mono-cropland of corn and soy commodities that are destined for industrial animal feedlots, fuel refineries, and chemical manufacturers. Products forged here are shipped across the globe. Such large-scale agriculture not only connects this stretch of river with climate change but also the total transformation of the Prairie’s biome.

Field Station 3: Anthropocene Vernacular

– This field station targets the St. Louis region with its palimpsest of “memories, meanings, and anxieties” at work for over a millennium. The once-great Mississippian culture and their earthen pyramids is overlain a metropolitan city grappling with interconnected legacies of industry, race, and empire. Here, the Mississippi cleaves through a territory “rife with contradiction.” The former meeting point of the Osage, Illinois, the Cahokia, and Missouri, became a boundary between colonial empires and, later, a dividing line between slavery and freedom.

Field Station 4 – Confluence Ecologies

– In “confluence territory,” the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers meet in south Illinois and Western Kentucky. This field station looks at the confluence of pharmacy-driven addiction and our dependencies on coal and nuclear power. It likewise takes up other confluences – such as native species loss and invasive replacements; and issues surrounding animal labor, future terraforming, and geoengineering.

Field Station 5: Commodity Exploitation

– This field station covers the Upper and Lower Delta region from Memphis to New Orleans, which is shaped by interactive dynamics of the changing environment and its influence on social, economic and multi-ethnic racial identities of the South. It considers ways these cultural factors “spatially construct” this Delta region by considering the spatial politics of urban and rural areas between Memphis, Jackson, Miss. and New Orleans. It will explore how spatial politics contributed to the river’s footprint in environmental, economic, and social terms.

Once students are grounded in the multi-scale and interdisciplinary nature of Anthropocene as a concept, they will attend at least two public events of their choice. Events will be spread throughout New Orleans each evening during the week as well as day-long weekend events that bookend the conference.

Separately, conference participants who applied and were accepted by the host committee were given a choice to participate in two multi-day seminars, which we selected among a half dozen. These seminars, led by experts, scholars, and activists, will each lead about 40 participants through unexpected places along the river that address the faces of culture and environmental impact of the Mississippi. My two are entitled, “Exhaustion and Imagination;” and “Commodity Flows.”

“Exhaustion and Imagination,” led by Monique Verdin, a native daughter of the southeastern Delta, Tulane visual artist Adam Crosson, and sound artist Monica Haller, will explore the limitation – and opportunities – that exhaustion creates. As we have exhausted the natural resources of the disappearing land in south Louisiana, those seeking to correct this phenomenon are likewise exhausted. We have exhausted our options and our resourcefulness. We have exhausted our bodies and spirits. The Anthropocene confronts us. This seminar asks whether certain kinds of interventions have reached their useful limits and invites us to imagine new kinds of possibilities from this cessation.

By visiting multiple sites downriver from Tulane University – including disappearing native ancestral lands outside of the levee system in Plaquemines Parish – the seminar will explore the roles of exhaustion and imagination that inform each other as we unpack the anthropogenic layers expressed upon and within the landscape.

“Commodity Flows,” led by Thomas Turnbull and Scott Eustice with Healthy Gulf, frames the river as a vector of trade, labor, and commodities. We will consider the world’s addiction to sugar as we visit the sugarcane fields and plantations of the Lower Delta. We will think about the “molecular relations” of industrial chemistry that flow through the nitrate emissions of fertilizer used to plant the harvests that once drove chattel slavery into the delta. We will ask how the river functions as a thru line connecting the mono-agriculture cultivation of sugar to the factories and plants of cancer alley. From fertilizers to plastics to sugar, the industrial hydrology of the river can carry us back through time to the same geography of plantations that reflect a violent history of exploitation on the social and natural systems that play out today.

These topics – like the concept Anthropocene — are complex, as well as a little abstract. But they are meant to open possibilities and ideas rather than reduce and foreclose. And, hopefully, we may come to know ourselves and the river through a new partnership. Our goal is to start a conversation that can lead to new kinds of actions – in a dynamic and fragile landscape that at the least deserves our fullest attention.

Further readings:

Klein, C. A. and S. B. Zellmer Mississippi River tragedies : a century of unnatural disaster.

Randolph, N. (2018). “River activism, “levees-only” and the Great Mississippi flood of 1927.” Media and Communication 6(1).

Grabar (June 18, 2019). “Hell Is High Water: When will the Mississippi River come for New Orleans?” Slate.com. (Accessed: Oct. 14, 2019)

Shallat, T. (2006). “Holding Louisiana.” 47(1): 102-107.

Barry, J. M. (1997). Rising Tide: the great Mississippi flood of 1927 and how it changed America. New York, Simon & Schuster.

Haraway, D. (2015). “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6: 159-165.

McPhee, J. (1989). The control of nature. New York, Farrar, Straus Giroux.

Randolph, N. (2018). “River activism, “levees-only” and the Great Mississippi flood of 1927.” Media and Communication 6(1).

Twain, M. (1883). Life on the Mississippi. Boston, Osgood.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

[…] Tulane, students this November entered into wider conversations about the human toll generated by the current Anthropocene epoch in which we now find ourselves […]

Anthropocene….Doesn’t it sound like obscene crashed into an android?