Editor’s Note: In honor of the Improv Conference New Orleans: A Festival of Ideas, which will be held November 8-10, we are re-running the interview between Renee Peck and local author Randy Fertel, who will be holding a lecture at the conference with Michael Pollan and Mark Plotkin on Friday, November 8. This piece was originally published on November 29, 2018.

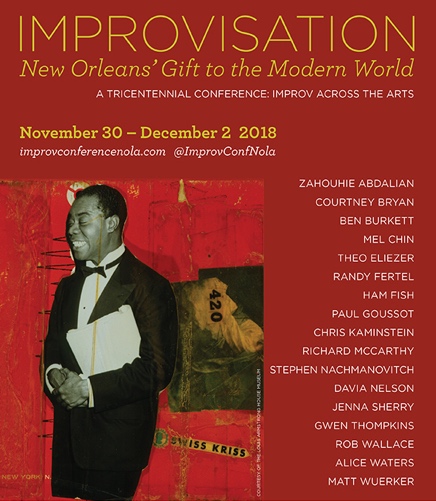

Randy Fertel talks improv across the arts (Photo: improvconferencenola.com)

We recently talked to local author Randy Fertel about Improvisation: New Orleans’ Gift to the World, a three-day conference devoted to our historic ability to, well, pivot. The event, taking place Nov. 30 to Dec. 2, is an outgrowth of Fertel’s latest book, A Taste for Chaos, which also explored the idea of improvisation, within the literary arena. But first, a few details about the conference.

Q: The dictionary definition of improvisation is “to create without preparation.” Is that a good start for what you’re studying here?

Fertel: Another word for improvisation is impromptu, a word that stems from “at the ready.” Improvisers present themselves as creating without preparation, in the moment. One form this takes is the Eureka moment, when an idea bursts forth without conscious effort or thought.

But as one of our speakers, Rob Wallace, writes, “there is no improvisation without reference to structure.” Our speakers will explore the paradox that improvisers must negotiate the tension between structure and freedom: how one readies oneself to be ready.

Improvisation: New Orleans’ Gift to the World explores a unique part of the city’s psyche (Photo: improvnolaconference.com)

And what speakers we have! Alice Waters of Chez Panisse (often ranked in the best restaurants worldwide), Peabody Award winning Kitchen Sister Davia Nelson and farmer/activist Ben Burkett will explore how one starts with a recipe, a structure, and then improvises with what is seasonal and available. Conceptual artist Mel Chin, whose NOMA Rematch exhibit at Prospect 1 was a big hit locally, will explore with local artist Theo Eliezer the subjectivity demanded by his work in Augmented Reality. Three native New Orleanians, Courtney Bryan, Jenna Sherry, and Zarouhie Abdalian (whose show is up currently at the CAC), will explore the intersection of jazz, classical, and visual arts. And lots more: improv in literature, improv in politics (our president, the bizarro improviser), and even improv in life.

How does one become ready? Counter-intuitively, one step is to do nothing. Literally. Mark Jung-Beeman, a cognitive neuroscientist at Northwestern, has determined that “if you want to encourage insights, then you’ve got to encourage people to relax.” He explains: “The relaxation phase is critical. … That’s why so many insights happen during warm showers.” Archimedes set the pattern when he had his Eureka! moment about water displacement in the tub.

In fact, if you want to convince your boss of something, you have two basic choices: you can say, I did all the research, here are all the good reasons; or you can say, I had a great idea in the shower this morning. Brainstorms like that carry a certain value: they convey a certain authenticity that makes the well-thought out idea seem artificial or self-promoting (look how smart I am/look how hard I work). Of course, while seeming not to be reaching for effect, the rhetoric of spontaneity affects the audience in much the same way: look at what I created without even trying; I’m working for you even in the shower! We are always trying to establish our authority, but it is striking that improv’s rhetoric is counterintuitive: I didn’t work on this; I’m presenting my idea carelessly, off the cuff.

More natural and spontaneous, improvisers have been exploiting that rhetoric, or device of persuasion, since antiquity. While the mainstream of western culture values rationality, objectivity, artifice, and care, under the guise of improvisation other values come to the fore: the non-rational (intuition, instinct, the subconscious), subjectivity (acknowledging that both artist and audience shape what we see), naturalness, careless spontaneity. Where the mainstream values mastery over the world and oneself, the improviser longs to be mastered (by the muse, a dream, by his or her art, etc).

If you doubt the power of this rhetoric of spontaneity, consider the present resident of the White House who doesn’t read briefing books, who has really good instincts, who doesn’t trust his intelligence(!) services, and who doesn’t need to read a book about NATO, he just knows it’s bad. Apparently, at least 35% of the electorate finds his know-nothing, spontaneous self-presentation convincing. Politico’s cartoonist Matt Wuerker will explore this dark, bizarro version of improv with local public radio host Gwen Thompkins, Slow Food USA’s CEO, New Orleans native Richard McCarthy. The session at 4:30 Saturday will be moderated by New York Times columnist Rob Walker.

But back to readiness: In a sense the improviser’s readiness is just the tip of the iceberg. What about the long hours preparing to be “at the ready”? Jazz musicians call it woodshedding. Quintilian, the first century rhetorician who had a huge influence on the Renaissance, first described it: one is constrained to master the skills of oratory in order to become skillful; once skilled, the improvisatory function kicks in and one is no longer constrained. It becomes clearer why the rhetorical tradition since Quintilian has placed improvisation, tapping such power, as the culmination of its art, “The greatest fruit of our studies, the richest harvest of our long labor.”

So, there’s this paradox at the heart of improvisation’s readiness: you must have worked hard to be free to create without working. One must first become of master craftsman; then with luck you will be mastered: inspired by the muse, or some dream, or that good bottle of bourbon. Faulkner, whose elaborate prose gives the impression of a man thinking, said all he needed to write was tobacco, a bottle of bourbon, and an empty room. In whisky veritas, apparently.

If I was as good a writer as Faulkner, my answer would have been as short. J

Q: I’ve heard it said that New Orleanians know how to live in the moment. Is that one aspect of improvisation?

Fertel: Yes, improvisers present themselves as living totally in the moment, skating on the thin ice of the present tense. The great Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska playfully points to life’s essential challenge, that

Nothing can ever happen twice.

In consequence, the sorry fact is

that we arrive here improvised

and leave without the chance to practice.

Even if there is no one dumber,

if you’re the planet’s biggest dunce,

you can’t repeat the class in summer:

this course is only offered once.

So, we are all born improvisers. And the successful improviser is he, or in this case, she who manages to meet that challenge, that each present moment is unlike any other. The past cannot serve as an adequate model. And all the possibilities in the present moment make the future uncertain.

An example: Some New Orleanians were once entertaining some New York friends at Galatoire’s. The host asked his friend to compare our dining scene to New York’s. “Well,” came the response as he looked around the beautiful mirrored room, “here everyone is focused either on their meal or their convivial table conversation; in New York they would be looking over their shoulder to see who was there and what they were doing.”

Of course, New Orleanians are in the habit at table of talking about their last meal or their next. In so doing do we fail to meet the challenge, or is the past and future an intimate part of our present? Improv explores such conundrums.

Of course being present in this moment, now, is the first tool in the improviser’s tradecraft. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls that state flow and describes it as “optimal experience.” British Modern novelist D.H. Lawrence presents in his poetry the figure of “Man Thinking” who achieves “the direct utterance of the instant, whole man.” Such an improviser is “instant” (from Latin, instare, “to stand in” or “on”) in more ways than one. He stands before us, made immediate to us by the dramatic presence of his voice. What he performs is in the instant, flowing from moment to moment, each moment un-fore-seen (im-pro-vised).

The one rule of comic improv is that whatever is proposed, you must say, Yes, and…. If you say no, or but, you lose the comic improv challenge. This is related to the improviser’s openness to the passing moment. The improviser says a big yes to the world as it passes. Nothing is too small or beneath his avid attention. The improviser doesn’t just seize the day (carpe diem), he seizes life it all its cornucopian fecundity: carpe vitam. When I commissioned the painting of Hermes the Trickster by local artist Alan Gerson, I asked that he work carpe vitam into his portrait. It’s there half-hidden behind Hermes’ winged helmet.

Early improv theorist Johnstone puts it this way: “There are people who prefer to say ‘Yes,’ and there are people who prefer to say ‘No’. Those who say ‘Yes’ are rewarded by the adventures they have, and those that say ‘No’ are rewarded by the safety they attain.”

So by embracing the passing moment, improv is a call to adventure.

Q: It sounds to me like you’re looking at improvisation as a mindset, an attitude, in the way we live.

Q: It sounds to me like you’re looking at improvisation as a mindset, an attitude, in the way we live.

Fertel: You’ve got that just right: improvisation is a mindset, an attitude, one way we live at least part of the time. Being present is part of it, being in the zone, relying on muscle memory as an athlete or musician does. But the paradox of improv is that that mindset while always striving to be present is always inevitably (if sometimes only implicitly) set in dialogue with some less improvised approach to life. When the 17th court century courtly poet Robert Herrick praises “Julia’s Clothes,” the stuffiness and straitlaced attire of the court implicitly sets off Julia’s “glittering” carelessness (even though Herrick does not mention the court’s starched ruffles):

When as in silks my Julia goes,

Then, then (methinks) how sweetly flows

That liquefaction of her clothes.

Next, when I cast mine eyes, and see

That brave vibration each way free,

O how that glittering taketh me!

So the mindset is not just a state of being present which the improviser demonstrates and induces us to imitate. The challenge of staying present is implicit. We all have a hard time not looking over our shoulder. Ask any Buddhist how long he or she can manage to be free of desire. Our almost constant companion, desire takes us out of the present, longing for something gone or for something to come. So, insofar as he demonstrates presence, the improviser is kind of a Zen monk, a rambunctious one but Zen nonetheless.

Q; You also talk about improvisation as being a process of opposites: mastery versus experimentation, or structure versus freeform. Is there a kind of tension inherent in improvisation?

Fertel: Well, I’ve gotten ahead of you, I guess. Yes, improv presents itself as free flow, free of conflict, and something you’ve never seen before: pure innovation. But, never entirely pure, it’s always in dialogue with some kind of art or discourse that the improviser is implicitly criticizing. So, some reverse “model” for this “utterly new” art is the stuffier, more straitlaced art the improviser is debunking: mere craft.

Reaching for an “art beyond the reach of art,” Jackson Pollock’s swirls of paint in his “action painting” are an answer to representational art. What is presented as art is not an imitation of some object in nature, but the state of mind of the artist as he moves around his canvas swirling paint (a nervous but rapturous state of mind perfectly captured in the Ed Harris bio-pic). The same can be said of poet/physician William Carlos Williams deceptively simple, title-less poem:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the

white chickens

In some measure, the poet doesn’t seek to create an artifact, a representation of this scene: red wheel barrow, etc. At least that is the rhetorical thrust of his art. Williams fulfills what French avant-garde performance artist Yves Klein expresses: “My works are only the ashes of my art.” Williams seeks not only to express but to transcribe or portray, as it were, a state of mind, neither orderly nor cogent, that could experience such odd thoughts: red wheelbarrows are breathlessly important. Williams’s follower Allen Ginsberg seeks “to transcribe … my own mind … in a form most nearly representing its actual ‘occurrence.’” French improviser Paul Valéry is even more explicit: “A poet’s function—do not be startled by this remark—is not to experience the poetic state: that is a private affair. His function is to create it in others. The poet is recognized—or at least everyone recognizes his own poet—by the simple fact that he causes his reader to become ‘inspired.’”

In a word, the real function of improvisations is to make us improvisers too, co-creators of the work of art. You must enter the flow state to be there with and to follow

the improviser in his flow state. Improvisation makes us improvisers.

By the way, I also prize Valéry’s remark that “everything changes but the avant-garde.” I think that captures the way improvisations are all the same over the centuries, always presenting itself as something new, something you’ve never seen before because it was created right before your eyes, and always challenging some too-rational, merely craftsmanly approach to art or life. Rabelais, Montaigne, Diderot, Wordworth and Coleridge, they are all self-consciously innovators and proclaim themselves improvisers. Modernism — the early 20th century artists who insisted as Pound said, to make it new — has many precursors. Everything changes but the avant-garde.

Q: I’ve always felt like I love New Orleans for the same reasons it can annoy me – that laid-back lifestyle can go both ways. Does that kind of oxymoron play into how or why we improvise life here?

Fertel: Indeed what attracted me to improvisation is that many of the great ones not only promote the improviser’s presentness and his/her embrace of life. They also explore improv’s dark side. Carelessness is not just a artistic style but a moral challenge. One familiar novel, The Great Gatsby, opens up in surprising ways when seen through the lens of critical improvisation. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece is about the Jazz Age and its carefree art and lifestyle. But it is also about the problem of carelessness. In what seems at first a throwaway moment, Fitzgerald tellingly conflates jazz’s improvisational quality with its kinetic power, its power to move us:

“Ladies and gentlemen,” [the conductor] cried. At the request of

Mr. Gatsby we are going to play for you Mr. Vladimir Tostoff ’s

latest work, which attracted so much attention at Carnegie Hall

last May. If you read the papers, you know there was a big

sensation.” He smiled with jovial condescension, and added:

“Some sensation!” Whereupon everybody laughed.

“The piece is known,” he concluded lustily, “as Vladimir

Tostoff ’s Jazz History of the World… .”

The passage is rife with subtle jokes. The composer’s mock-Russian name plays upon jazz’s trope of careless spontaneity: Tostoff = “tossed off.” His “jovial condescension” is directed at the absurdity of the idea that a Carnegie Hall, uptown audience could respond with enthusiasm, let alone the appropriate “sensation.” Stuffed shirts, they have no sensuality at all: “Some sensation!”

By contrast, the young ladies of the Jazz Age respond on Gatsby’s suburban lawn just as the music would have them respond: with a careless, libertine sensuousness, an openness to experience equal to the music’s own. The narrator continues: “When the Jazz History of the World was over, girls were putting their heads on men’s shoulders in a puppyish, convivial way, girls were swooning backward playfully into men’s arms, even into groups, knowing that someone would arrest their falls….” An odd response to a “History of ” anything, it is kinetic and empathic. They take on the spirit of the vibrations that pass through them

Most telling, they respond as if they could, like the music, sum up human history in their dance. Their summation lies in their gesture: a willingness to fall, “swooning backward playfully into men’s arms … knowing that someone would arrest their falls.” Such is the Jazz Age’s carefree version of the notion of felix culpa, the happy fall, not that it is happy that we fell from Eden by eating from the tree of knowledge, but that it can’t or won’t hurt, so why not? Chomp!

Certainly, the taste of that apple—the experience of this world—is worth a go. Pagans though they be, Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age dancers act as if, giving themselves up, they will not be taken advantage of, as if the disenfranchised are not exploited in the political and musical democracy that America represents. But of course, they are wrong: the novel explodes with demonstrations that, in fact, carelessness, like Daisy and Tom Buchanan’s, brings nothing but trouble. “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made….”

Improvisation’s carelessness is then both solution and problem. One reason narrator Nick Carraway is first “carried away” by the allure of the Buchanan’s East Egg carelessness is that in his native “[Mid-]West … an evening was hurried from phase to phase toward its close, in a continually disappointed anticipation or in sheer nervous dread of the moment itself.” Gatsby alone in the end is “exempt from [Nick’s] reaction.” Gatsby’s every act—from silk shirts to mansions in West Egg—is calculated toward a single end, winning Daisy. Sometimes thoughtfulness, even wrongheaded thoughtfulness, is the higher value, sometimes thoughtlessness.

Q: What is the best thing that improvisation has done for New Orleans? And the worst?

Fertel: Well, I could just say it helped shape Louis Armstrong, who invented the jazz solo, and leave it at that. Louis was a constant improviser, including in the collages he created on the reel-to-reel tape boxes that were recently shown at the New Orleans Jazz Museum (seen above in our flyer).

The only thing comparable to our invention of jazz improvisation, our gift to the modern world, as our conference proposes, was our role in creating the model for historic preservation, the tout ensemble approach, an idea that evolved, was improvised, out of a loose knit band of preservationists. In saving the French Quarter the little band revolutionized thinking among preservationists all over the nation.

There is talk of another conference on improv next year perhaps. There are so many disciplines and arts that improvisation touches. Improv is a meme in the business innovation world.

And I would like to explore urban planning. Jane Jacobs, enemy par excellence of rationalist-driven master plans, saw the “art form” and “complex order” of the city to be characterized by freedom and to be the result of improvisation:

“Under the seeming disorder of the old city, wherever the old city is working successfully, is a marvelous order for maintaining the safety of the streets and the freedom of the city. It is a complex order. Its essence is intricacy of sidewalk use, bringing with it a constant succession of eyes. This order is all composed of movement and change, and although it is life, not art, we may fancifully call it the art form of the city and liken it to the dance — not to a simple-minded precision dance with everyone kicking up at the same time, twirling in unison and bowing off en masse, but to an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole. The ballet of the good city sidewalk never repeats itself from place to place, and in any one place is always replete with new improvisations.”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.