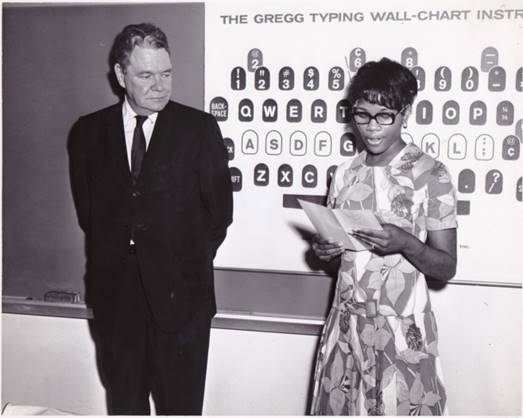

Dr. Sandra O’Neal giving a presentation to Congressman Hale Boggs in 1970. (Photo by: Dr. Sandra O’Neal )

The last decade marked the fiftieth anniversary of countless moments in the New Orleans civil rights movement. In 2010, we remembered the four African-American students who integrated the New Orleans public schools. That same year, non-violent activists were arrested at a sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter on Canal Street. Ten years later, New Orleanians of color were still fighting for basic forms of equality, many in unseen ways. Dr. Sandra O’Neal was one of those people.

O’Neal is part of a generation of unsung civil rights heroes, what she calls “the first class of black women to integrate corporate America.”

But her working life began years earlier. At the age of 16, O’Neal faced the reality that she needed to drop out of school to help take care of her family. “It was the saddest time of my life,” she said, remembering back to the moment her sister was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver. Their mother’s departure from work to take care of O’Neal’s sister meant that O’Neal had to find a way to make up for that lost income.

That same week, she came home to an eviction notice on her family’s door. “I was just envisioning all of our things on the street,” O’Neal recalled. As the immediacy of her circumstance began to sink in, she returned to school and found herself fundamentally altered. “I looked around at everyone planning for prom, and girls laughing, and boyfriends, and I said, ‘This is not the real world. This is not my world.’”

Her new world focalized in the back of the house at Tony’s Spaghetti, earning seventy-five cents per hour and working until 1am each night. It was enough to make ends meet, but her sister passed away during that time. Even now, O’Neal can’t find clarity within that memory. “It wasn’t real. I guess I was in big time denial. So that pretty much sums up high school for me.”

Four years later, O’Neal came across an ad in the newspaper directed toward African-American women interested in gaining secretarial skills. Starting work at 16 had produced a resumé that was limited to menial jobs — washing dishes and cooking in Bourbon Street kitchens. Welcoming the opportunity to try something different, O’Neal promptly enrolled at the Adult Education Center, an organization that catalyzed the racial integration of the city’s workforce.

O’Neal wasted no time in meeting the demands of her studies. She got up every morning to practice her typing and shorthand. The Adult Education Center invoked possibilities that were obvious to O’Neal from the very beginning. “It was a great opportunity for someone black who was from the projects, because there was nothing for us there,” she said. The curriculum offered an alternative path. “It was a gateway out of the projects,” O’Neal remarked.

Part of what made the Adult Education Center such an aberration was its teachers. At the core of this support system was Dr. Alice Geoffray, the school’s founding director. O’Neal noticed early on that Dr. Geoffray’s office door was open everyday, a signal that she was available for one-on-one sessions. The presence of a supportive mentor characterized a radical departure from the segregated public schools that O’Neal and other African-Americans of her generation had attended. At first, O’Neal thought her experience with Dr. Geoffray was the exception to the rule. “And then I come to find out she was like that with everybody. I thought I was special, but we were all special.”

Following her graduation from the Adult Education Center, O’Neal began working for Gulf Oil in 1970. Though she was eminently prepared to start her career, able to type 120 shorthand words per minute, she wasn’t primed for the culture shock she experienced. O’Neal remembered back to one day in particular when her boss, a white man, called her into his office and asked if she was happy there. To which she replied, yes.

“And I’m wondering, where is this going? I said ‘What’s the matter?’ He said, “You look different.’ I realized I had combed my hair out to this big Afro.” She laughed, recalling the bizarre interaction. “‘You mean, my hairstyle.’ And he said, ‘Yeah. Are you angry with us?’ I said, ‘No it’s just s hairstyle. It doesn’t mean I’m angry, it’s just the way I comb my hair.’ They took it as a form of militancy. We were new to them and they were new to us.”

O’Neal didn’t have to stay there for long. She soon qualified for a claims representative position at the Social Security Administration, a career that would span 32 years. Inspired by the immense need she saw within the welfare system, O’Neal decided to go back to school for a doctorate in social work at the age of 52.

Today, O’Neal teaches online social work courses — among her favorites are Social Work Policy and Research Ethics. Many of her students are mothers with children, and the challenges they face are a throughline from her generation to theirs that is not lost on her.

In October, the Adult Education Center hosted a fiftieth reunion. The gathering was, in O’Neal’s words, “one big, glorious affair.” Many of the women who completed the program diverged in career path upon graduation, so it was, for many, their first opportunity to catch up in decades. The reunion also provided a venue to dedicate scholarships for young students.

O’Neal has four children of her own, and they all grew up in an environment where education wasn’t just available, it was the only option on the table. “My children didn’t have the choice whether they were going to go to college or not. I brought them to LSU kicking and screaming. Education was top priority.”

O’Neal’s education story is one of deep reciprocity. Becoming a professor carved out a space for her to pay tribute to the mentors who made indelible impacts on her own life, like Dr. Geoffray. But O’Neal is also quick to offer wisdom to anyone living in doubt. “If I could share anything, it would be that if you had it rough, and you thought that you couldn’t meet your dreams, you can still meet your dreams. No matter how old you are. I always say, try.”

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.