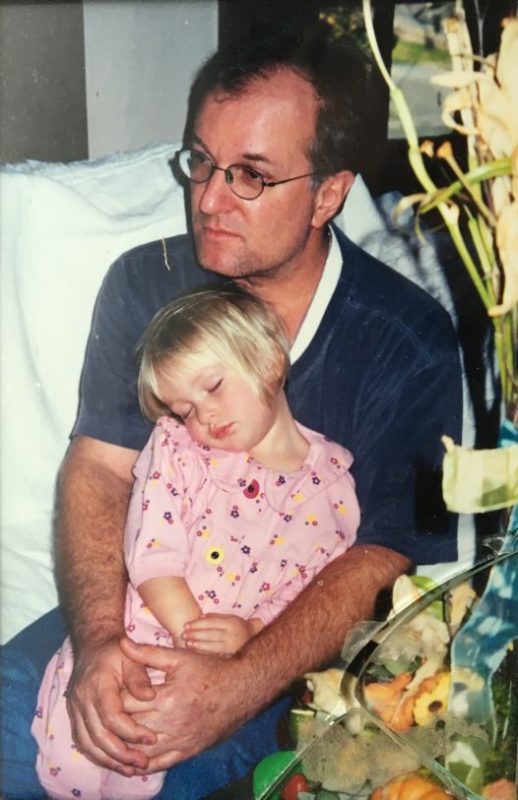

Lydia Straka and her father (Photo provided by: Lydia Straka)

Editor’s Note: The following series “Bold Females in the Big Easy” is a week-long series curated by Piper Stevens as part of the Digital Research Internship Program in partnership with ViaNolaVie. The DRI Program is a Newcomb Institute technology initiative for undergraduate students combining technology skillsets, feminist leadership, and the digital humanities.

We are coming up on March 9th, a day in which the world takes a moment to appreciate the powerful contributions of the female population in celebration of International Woman’s Day. This curation takes a moment to reflect on the powerful women and women-centered movements strengthening our New Orleans community. This piece about a conversation between author Lydia Straka and her father expresses a broader frustration and disconnect that exists between so many people of different genders and generations when discussing feminist issues. This was originally published on June 20, 2017.

“Women can be manipulative; women can have motives.”

I sat across from my father at his kitchen table. I had returned home from St. Louis for winter break during my first year of college. Earlier words he had spoken over the phone in October echoed in my head. I still hadn’t quite forgiven him for those, having to do with his adverse opinion about women stemming from the 2016 presidential election. That conversation had ended with me abruptly hanging up and us not talking for weeks. The election, me being away from home for the first time, and the independence I had gained while exposed to new ideas and experiences made a perfect storm for argument.

I wanted to be glad to be back in my city, but I struggled to find the comfort I had hoped for with the family disputes resurfacing. Tension from our disagreements sat in the humid New Orleans air, and the atmosphere grew heavier when feminism, specifically catcalling, came up.

I told him about the day a car drove past my high school and the passengers whistled at me, clearly a minor. I told him that when I was 14, walking in our neighborhood, a 40ish man on a bike slowed down and said to me, “Well don’t you look pretty.” My sister, from the other room, chimed in: When she was 12, a stranger on a beach called her sexy.

My dad replied that it’s natural for men to call out when they see a beautiful woman, using Italy as an example of women taking it with grace. I tried to convey to him the pressures and fear so deeply ingrained in women, in our city and around the world. Something isn’t right if simply being in public requires being constantly on guard and tense, even fearful for your safety. I tried to communicate that it’s not as simple as defending yourself or reporting a threatening encounter — women are taught from a young age to not respond when someone makes a predatory comment, for fear of escalating the situation. Nothing would persuade him.

My relationship with my father is not entirely strained. He’s always encouraged me to think. When I was little, he’d play classical music, asking me to tell him what I thought the stories were behind the notes. I’d come up with fantastical beasts and animals, and he’d revel in my imagination.

I feel most at home in my father’s house when we’re sitting at his kitchen table on a Friday evening, the night when my younger sister and I visit him, and we talk about life. As I’ve grown up, he talks about whatever he’s been reading — Carl Jung, A Confederacy of Dunces, Buddhist philosophy — and shares his thoughts. As I explained in last week’s article, he urges me to “always dig deeper.” There are layers to experience, so don’t trap yourself in a box. Cast away falsehoods, and continually strive for what’s real. I take it seriously.

I left New Orleans with him for the first time last summer, to go to New York City. We visited museum after museum. He, being an artist, gushed about the Picassos, the Degas, Hieronymus Boschs, and everything in between, marveling at my appreciation for Cezanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire. Art was a break from the clashes that usually tarnish our conversations, a middle ground, something we could agree on. He says that at the core of it all, he wants me to think my own thoughts.

So when we argued at that same kitchen table, all I could think about was his box analogy for life, and what a box he seemed to be in. I thought, if he can’t listen to a woman’s opinion on the pressures that hold her back from feeling free in the world, then who can he listen to? My dad countered that feminism is a box of my own. We argued back and forth, with no agreement, until I walked away in silence.

Trying to sleep, I found a knot in my stomach. I missed my friends at college, the reassurances they gave me whenever I got off the phone with my dad. At school, we all agree that a driven woman is someone to celebrate, so why must my father criticize a woman for having motives?

Our argument left me feeling as if I had just left home, not that I was back.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.