Folwell Dunbar: writer, educator, island builder, and Bob Dylan super fan. (Photo provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2016, several of my literary friends balked. “He’s not a real writer,” they said. “The Bard from Hibbing my ass!”

“Ya ever read Tarantula,” asked one? “I couldn’t get through it. Chronicles was o.k., but I bet ya he had a ghost writer.”

You mean the guy who wrote, “And later on, when the crowd thinned out, I was just about to do the same,” asked a middle school English teacher? “He obviously never read The Elements of Style. No, he doesn’t deserve a Nobel Prize – a Newbery Medal perhaps.”

“I disagree,” I said. “In my opinion, it’s long overdue. For at least the past 40 years, he’s been the man in me.”

None of my friends got the song reference, nor its significance. Instead, they jabbered on about Dylan’s voice (or lack thereof), his infamous religious period, and their favorite line from his autobiography, “There are many places I like, but I like New Orleans better.” In that, at least, we could all agree.

~

When I was in 8th grade, I bought a small brown briefcase that held 15 audio cassettes. My first 10 were all Beatles. I then added the Best of the Doobie Brothers (I loved “Black Water.”), The Doors’ and The B52’s first albums, and Reggatta de Blanc by The Police. My older brother suggested I fill out the case with something by the Rolling Stones. “Get Some Girls or Beggar’s Banquet,” he suggested.

But, before I could get to the store, a friend of mine handed me a cassette with a cracked case. “It’s ‘Blood on the Tracks’ by Bob Dylan,” he said. “It’s one of my all-time favorites. I’ve already got it on vinyl, and I’m thinking about breaking down and getting one of those new fancy CD’s. You take it.”

We put the tape in my boombox and listened to it straight through, from “Tangled Up in Blue” to “Buckets of Rain.”

That’s all it took; I was hooked. By the end of the year, I had listened to it so many times, the tape finally gave out.

For high school, I was shipped off to a New England boarding school. My dorm master, Latin teacher, football coach and mentor, Bill Poirot* was a huge Dylan fan. He introduced me to Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde on Blonde, The Basement Tapes, and Nashville Skyline.

In my junior year, I upgraded my briefcase to one that held 30 cassettes. Dylan now occupied more space than even the Beatles. Speaking of, George Harrison teamed up with Dylan that year to form the supergroup, the Traveling Wilburys. Their debut album, Vol.1, became the soundtrack of my summer.

By the time I graduated from high school, I was a full-blown Dylan fanatic.

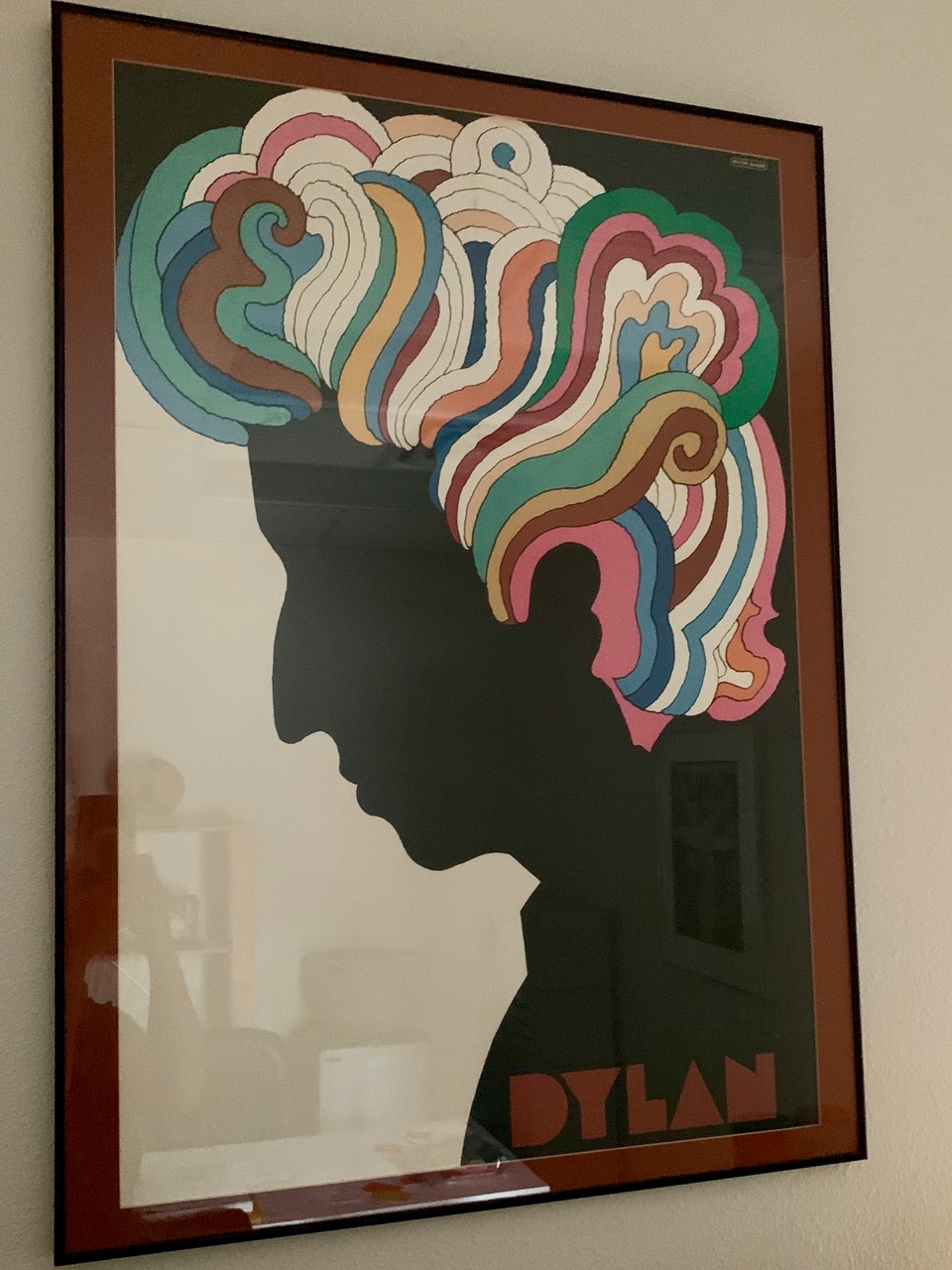

My freshman year in college, I walked into a friend’s dorm room and saw a poster on the wall. It was Dylan’s unmistakable profile in silhouette with an explosion of psychedelic hair. “Dude, that poster’s awesome,” I exclaimed! “Where did you get it?”

“It was in the vinyl version of Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. II,” he said. “Came out in the early 70’s. Hard to come by today.”

I spent the next four years searching for that poster. (Keep in mind, this was long before the age of eBay and craigslist.) Whenever I came across a record store, I would gallop in, and rifle through the D’s. I sometimes found the album, but, inevitably, it was missing the insert.

After college, I joined the Peace Corps and set off for Ecuador. In the tiny Andean village of Lloa, I shared the story of my unsuccessful quest to find the Dylan poster with my cohort. Our trainer laughed, reached into a trunk, and pulled out the poster. “You mean this one,” he asked? “Tenerlo, have it.”

Milton Glaser’s famous poster has adorned at least seven different walls of mine since.

The poster from Ecuador on the author’s office wall. (Photo provided by: Folwell Dunbar)

My obsession with Dylan sometimes interfered with my studies and relationships.

For a final exam in a US History course in college, I framed up every answer with Dylan’s song, “Watching the River Flow.” My professor gave me a disappointing B. “Very creative,” she said, “but the musical reference was a bit of a stretch, to say the least.”

In an economics class, I did an epic multimedia presentation using Dylan’s song, “Sundown on the Union.”

Well, it’s sundown on the union

And what’s made in the USA

Sure was a good idea

‘Til greed got in the way

My professor questioned Dylan’s credibility as a scholarly source, and my classmates all accused me of being a socialist.

For a graduate class in Education, I designed an entire high school curriculum around the many phases of Dylan’s career. My professor found it “intriguing,” but pointed out that there were no state or national standards relating to the singer/songwriter.

“Maybe there should be,” I suggested.

In regard to relationships, Dylan was hit or a miss, with the latter being far more numerous.

I painstakingly spliced together “mixed” tapes with songs like “I Want You,” “Wallflower,” “To Be Alone with You,” and “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” and I serenaded dates with lines like, “If not for you, my sky would fall / Rain would gather, too / Without your love I’d be nowhere at all / I’d be lost, if not for you.”

Unfortunately, my good intentions were often undermined by Dylan’s nasal, gruff growl and/or his use of terms of endearment like “honey” or “baby.” “What kind of chauvinistic pig would expect ME to just lay across their big brass bed,” one (extremely) liberal arts major yelled!

I once had a potential love interest who shared a ride with me back to college. We drove all the way from New Orleans to Durham, North Carolina in my 1972 VW Super Beetle, which, by the way, was “super.” I figured it was the perfect time to convert her to “Dylanology.” Somewhere around Greenville, South Carolina, she pounded the dashboard and screamed, “I’m &%$# over Dylan!” In other words, she was over me.

Whenever a relationship failed, I convalesced with Blood On the Tracks, arguably the greatest break-up album of all time.

Sundown, yellow moon

I replay the past

I know every scene by heart

They all went by so fast

If she’s passin’ back this way

I’m not that hard to find

Tell her she can look me up

If she’s got the time

If a relationship ended badly, I sometimes retaliated (I’m not proud.) with barbed lines from songs like “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”:

I ain’t sayin’ you treated me unkind

You could have done better, but I don’t mind

You just kinda wasted my precious time

Don’t think twice it’s alright

Or, this doozy from “Positively 4th Street”:

I wish that for just one time

You could stand inside my shoes

And just for that one moment

I could be you

Yes, I wish that for just one time

You could stand inside my shoes

You’d know what a drag it is

To see you

When I met my future wife, I told her that there were three non-negotiables: Football (playing, not watching), Dylan and dogs. On our third date, I actually sent her home with a book of Dylan’s lyrics. It should have been a deal-breaker, but, fortunately for me, it wasn’t.

To this day, my wife loathes football, tolerates Dylan, and, thankfully, absolutely adores our dog. So much for non-negotiables.

Over the years, Dylan has played a huge role in my professional life. After college and Peace Corps, I became a teacher. I taught middle and high school social studies. Dylan’s discography was practically one of my textbooks.

I used “Tangled Up in Blue,” “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest,” “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts,” and “Hurricane,” to teach storytelling. I played “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Masters of War,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” “Maggie’s Farm,” “Oxford Town,” “With God On Our Side,” and, of course, “The Time’s They Are a Changin” to address conflict in the 20th century.

I told my students that Dylan’s songs were this generation’s version of Ben Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac. I used his sage advice for writing prompts and discussion topics: “Don’t need a weather man to know which way the wind blows,” “money doesn’t talk, it swears,” “he not busy being born is busy dying,” “when you’ve got nothing, you’ve got nothing to lose,” “to live outside the law, you have to be honest,” and “all the truth in the world adds up to one big lie.”

If I were teaching today during the coronavirus pandemic, I would certainly offer up a little solace via “Buckets of Rain”:

Life is sad

Life is a bust

All ya can do is do what you must

You do what you must do and ya do it well

I’ll do it for you

Honey baby, can’t you tell?

I would also suggest listening to “Every Grain of Sand” from Shot of Love or his latest release, “A Murder Most Foul.”

I recently ran into a former student of mine. I asked her the question I ask all my former students: “So, what did you learn in my class?”

“I have to be honest Mr. Dunbar,” she said, “I don’t remember much. But, you did turn me on to Dylan.”

I smiled wryly and murmured, “Ah, success.”

As a writer, I may have learned more from Dylan than I did from all my classes combined.

The Bard of Hibbing showed me how to use (and not abuse) alliteration with songs like “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue,” and “To Ramona”; he taught me about surrealism with lines like, “jelly-faced women sneezing, jewels and binoculars hanging from the head of a mule”; and he showed me how to incorporate dialogue into prose with songs like “Highway 61 Revisited”:

Oh, God said to Abraham, “Kill me a son”

Abe said, “Man, you must be puttin’ me on”

God said, “No” Abe say, “What?”

God say, “You can do what you want, Abe, but

The next time you see me comin’, you better run”

Well, Abe said, “Where d’you want this killin’ done?”

God said, “Out on Highway 61”

And, when it comes to setting a scene or establishing a tone, nobody does it better than Dylan:

A worried man with a worried mind

No one in front of me and nothing behind

There’s a woman on my lap and she’s drinking champagne

Got white skin, got assassin’s eyes

I’m looking up into the sapphire-tinted skies

I’m well dressed, waiting on the last train

My list of favorite literary characters from the 20th century includes Ignatius J. Reilly, Holden Caulfield, Binx Bolling, Kilgore Trout, and The Little Prince. Not surprisingly, it also has characters from Dylan’s rather extensive songbook: The Hysterical Bride, The Man in the Long Black Coat, Mr. Jones, Isis, Cinderella, Jokerman, and Louise Who Holds a Handful of Rain to name a few.

In college, I was a huge fan of Robert Frost, T.S. Eliot and Pablo Neruda. I read everything they wrote. But, if you asked me today to recite one of their works, I would be at a loss. Dylan is a different story; I could ramble on for hours. By putting it to music, he made poetry far more accessible. Whenever I listen, I can’t help but smile.

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky

With one hand waving free

Silhouetted by the sea

Circled by the circus sands

With all memory and fate

Driven deep beneath the waves

Let me forget about today until tomorrow

Yes, Bob Dylan definitely deserved the Nobel Prize.

~

A friend recently asked, “Who were the three most influential people in your life”?

“That’s easy,” I said, “my dad, Mr. Poirot, and Bob Dylan.”

“You know Dylan,” she asked?

“No,” I said, “just the music.”

“Ya remember the opening song from The Big Lebowski,” I asked? “Well, Dylan, or at least his music, is the man in me.”

* At Mr. Poirot’s funeral, everyone who spoke, including me, referenced Dylan. And, of course, during the reception we played “Forever Young” on a loop:

May your hands always be busy

May your feet always be swift

May you have a strong foundation

When the winds of changes shift

May your heart always be joyful

May your song always be sung

And may you stay forever young

Folwell Dunbar is an educator and artist from New Orleans. He is the author of He Falls Well: A Memoir of Survival. When he isn’t busy reviewing lesson plans or scribbling drivel, he can be found listening to (or reading) Bob Dylan. He can be reached at fldunbar@icloud.com.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.