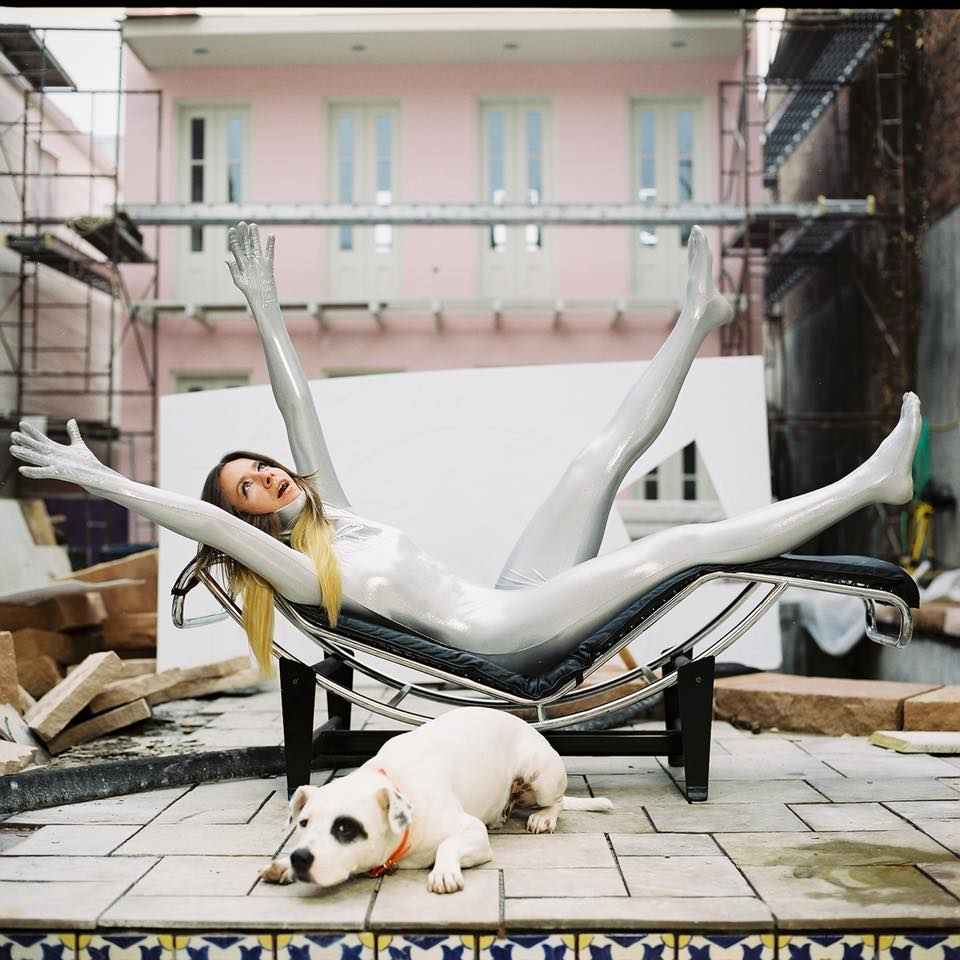

Tiana Hux. (Photo provided by: Tiana Hux)

Tiana Hux is a performance artist and arts educator to the most vulnerable populations in New Orleans. Hux performs as both the lead singer of her rock and roll band, Malevitus, as well as MC Sweet Tea, a solo act that is part of a genre she coined “burlesque review.”

Hux’s journey as a performance artist began in her hometown of Houston, Texas. As a child growing up in suburbia, her first window into another world was through MTV. Inspired by the music videos, Hux decided to enroll at the Art Institute of San Francisco. After a semester, she transferred to the University of Texas at Austin to be closer to her friends and family. While studying in Austin, Hux was introduced to her professor turned mentor, Linda Montano. Montano paved the way for performance artists in the 1970s and 1980s by establishing performance art as a new genre. As Hux’s professor, she introduced several ideas that Hux continues to incorporate in her work today. Montano presented the idea that duration and time are integral parts of any performance art piece. She also discussed her theory that life is art, and art is life. In other words, anything executed with commitment and with the intention of being art is art. Learning about Montano’s commitment to her performance art pieces, demonstrated by both the year she committed to being chained to another artist and the six month period when she wore the same color everyday, inspired Tiana Hux to not only devote her entire self to her work, but to also constantly evolve and push the boundaries of her creativity.

After college, Hux moved to New Orleans, where she realized she could combine her newfound love for hip-hop, dance, and being center stage by functioning as a master of ceremonies (MC) in her own show. Unfortunately, after releasing her first album, Hux was forced out of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina.

Hux moved to Los Angeles, California, where she struggled to find an authentic community of artists. Although she worked alongside many famous creatives, she found the culture of LA to be more commercial than she wanted.

Hux then had a brief stint in Austin, Texas, before finally returning to her spiritual home, New Orleans. Hux was immediately embraced by the rich and historical arts culture that continued to thrive in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Although the progressive nature of Austin gave her permission to think big and push her performance, the music scene was dominated by male singers with guitars. In New Orleans, Hux not only felt more welcome to create her art, but also believed the hip-hop portion of her act would be better received in a city with hip-hop so deeply woven into its history. As a white female rapper, Hux challenges the traditional image of a rapper and presents a dichotomy between aggressive masculinity and delicate femininity, both of which she incorporates into her act. Female rappers are uncommon because the hip-hop and rap scene can easily intimidate those who do not fit the historical and social constructs originally associated with rap. Hux is careful to respect rap’s history and the culture that created it.

Hux was also inspired by the older jazz players that she met while working at Preservation Hall. Her work there led her to Voodoo Fest, where she played her first show after returning to New Orleans. At that time, Hux called her unique blend of dancers, hip-hop, and burlesque a “hip opera.” From there, her work evolved into what it is now known as “burlesque review.” Hux defines burlesque review as the traditional scantily clad women displaying their bodies through enticing dances, but with a twist. The twist is that she weaves a storyline throughout the performance that also includes jokes and deeper character development than a traditional burlesque show.

Since the beginning of her career, when she first tried to blend many established genres into one cohesive act, it became clear that Hux cannot be confined to one style, but instead moves fluidly amongst them all as she pleases. She is a uniquely eccentric character, able to portray both the feminine promiscuity expected from a burlesque show, as well as the brute, stereotypically masculine confidence associated with hip-hop and rap. Neither of these personas captures Hux as a whole, instead, she presents herself to her viewers as she pleases and is able to switch her disposition as it suits her art. To be eccentric is not simply, “out of the ordinary or unconventional performances, but also those that are ambiguous, uncanny, or difficult to read” (Royster, 12). While Hux is out of the ordinary, it is her ambiguity which speaks most to her eccentricity. She is constantly reinventing her performance, so much so that no two are exactly alike.

In addition to her unique ability to move fluidly between society’s expectation of gender roles, her performances are anomalies of their own. In her band, Malevitus, which roughly translates as “bad life,” she is the only female. Her own hard-hitting vocals are accompanied by an electric bass, an electric guitar, and a drum kit, making Malevitus a classic rock and roll band. Much of her discography opens with the bass to create a deep, strong rhythm. While the drummer and guitarist may deviate from the rhythmic foundation to produce emphasis and sound variation, the bass continues to anchor every song. Hux’s dynamic and demanding vocals cling to the tempo of the heavy, rousing instrumentals. At times, Hux increases her tempo to bring a sense of urgency to her listeners and decreases her tempo to add emphasis to certain lyrics. These patterns are common in punk music, where vocals are amplified to produce hard-edged melodies.

Hux writes raw pieces that are sculpted into eight, nine, or ten song cycles meant to be contemplated altogether. In her work “Iconic,” “Bred,” and “Fire Department,” Hux comments on pressing issues, such as the ever-increasing wealth gap, climate change, and the dependence on technology. Hux uses her background in performance art to architect a true performance, often with her own acting, props, and dancers, that help paint a fuller picture for the audience. When watching Hux perform, the fluidity with which she presents herself is evident, and her ability to evade being tethered to one identity and one genre is as unique as she is.

Today, amongst the chaos of the pandemic, Hux has found it difficult to write music. She is not interested in live streaming a performance for her followers and does not want to post her art online because she is most interested in audience engagement and the action-based nature of performance art. She believes the rise of social media platforms, such as Soundcloud, have democratized the music industry and made it increasingly difficult for artists to have a steady income. When she is not teaching, she is contemplating how she can use this period to transition to film and the visual arts with local photographers and videographers. When concerts do finally return, Hux believes outdoor venues will be best.

Although Tiana Hux’s artistic journey may seem unconventional, it is her ability to ebb and flow, regardless of her surroundings, that make her a standout artist. Hux’s identity, beliefs, and performance art are a direct result of her personal experiences in Austin, Los Angeles, and New Orleans. While her path appears to be ill-defined, she channels the discomfort of her surroundings into evolving her art and acknowledging the different cultures that have influenced her. Throughout her artistic journey, Hux remained committed to her work and pushing the boundaries of her creativity, so much so that she created her own genre, burlesque review.

References

Royster, Francesca T. Sounding Like a No-No: Queer Sounds and Eccentric Acts in the Post-Soul Era. University of Michigan Press, 2013. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.1586114. Accessed 05 June 2020.

This piece is part of the on-going series “The Social and Political Commentary of Music Reviews,” which is part of an Alternative Journalism course at Tulane University taught by Dr. Christine Capetola.

You can donate to Tiana’s tip jar here:

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.