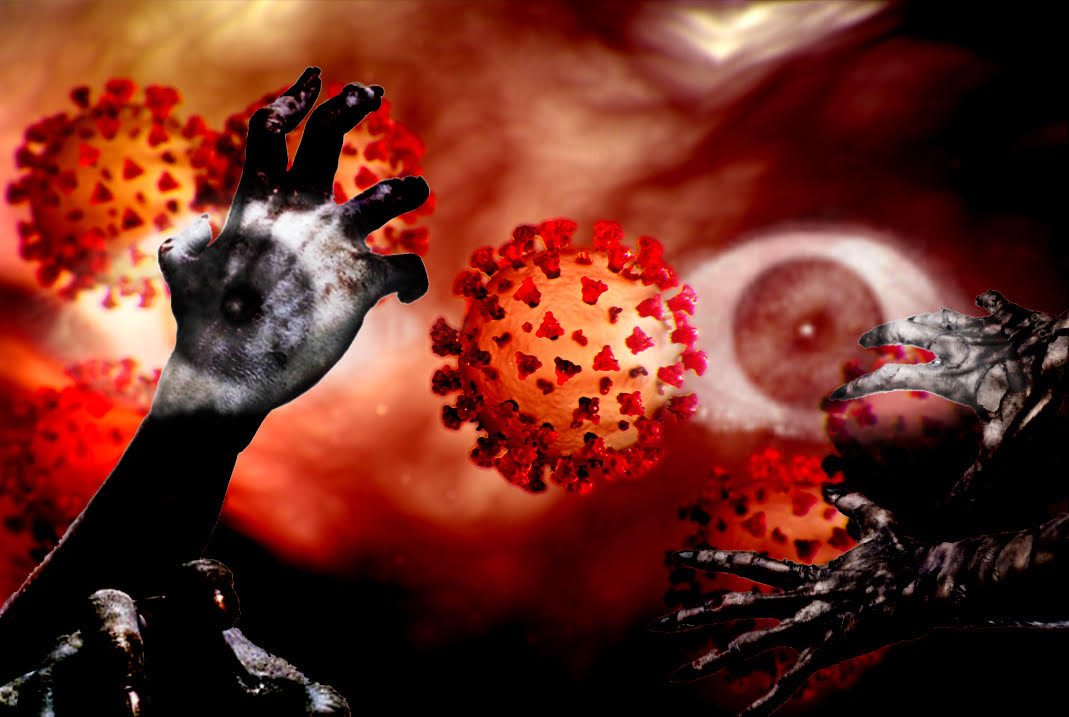

The invisible monster (Credit: Avery Anderson)

Glass shatters. The girl onscreen grabs a knife and barricades herself in the closet. You can’t see the monster, but you know he’s there, waiting to strike. As your palms begin to sweat and your muscles tense, movie magic can feel like a sickness. While the horror genre and the COVID-19 pandemic may seem worlds apart, these two “invisible monsters” are connected in a bizarre and often unexamined way: just as horror films force us to confront our own smallness and reckon with our own mortality, coronavirus has forced us to contemplate these once-imaginary fantasies in real time.

For local director and cosmic horror fanatic, James Roe, the connection between fantasy and the human condition is no mystery. “As a filmmaker,” James explains, “what’s most important [to me] is helping all of us, myself included, come to grips with the idea that the human race is a small drop in the bucket” in terms of “the universe’s history.”

Cosmic horror, also known as Lovecraftian horror, is a subgenre that plays upon human’s fear of the unknown. According to Roe, “it’s essentially [a genre in which] people are brought face to face with…their smallness.” Cosmic horror often incorporates elements of science fiction to represent the unknowable “other,” using aliens to represent forbidden knowledge and explore how humans interact with the incomprehensible. “The idea is that our reality as humans is a kind of a veneer that we place out there for ourselves to maintain our own sense of self importance and our own sense of purpose in the world,” Roe explains. But “if we take that veneer away,” as cosmic horror does, “it’s truly horrific to see how inconsequential we are in the great universe.”

James Roe, professor and film fanatic. (Photo: UNO)

When we work to comprehend the smallness of mankind, our newfound understanding prompts us to adopt a more universal perspective. This holistic mindset is especially important during a global pandemic. “Right now, I think there’s a lot of attacks on science,” Roe says. There are many people “not wearing masks” who refute or wilfully ignore what “scientists are telling us about the virus,” thereby putting others in danger. But cosmic horror, Roe says, works really well in these circumstances. “It helps reach out to those people in a way that a documentary might not.” While agents of anti-science can deny and discount the facts presented by other forms of media, cosmic horror “assaults them [on an] internal biological level.” According to Roe, “there’s [a] kind of…biological fear that can happen when you watch some of these movies or read some of these books, and I think that’s a good way of building empathy.”

In order to manufacture empathy offscreen, directors must first represent this feeling of smallness onscreen. “There’s two different ways of showing the monster or of having a monster inside of your film,” Roe explains. While the first technique shows the monster on screen in its full fearsome glory, Roe and other filmmakers often employ a different, more savvy technique. “Sometimes we don’t show the monster, which can be equally effective, sometimes more effective in my opinion.” In his own films, Roe prefers to not show the monster onscreen. When you withhold the monster’s concrete physicality from the audience, Roe explains, the audience is forced to face the monster that their mind constructs. “The human imagination is much more powerful than anything that we can show [onscreen].” By denying the audience a visual “explanation” of the source of the terror, it makes viewers more uncomfortable. When “there’s not necessarily an explanation behind the evil…that they encounter,” filmmakers are able to deny “the audience the reality of the creature…[while] also denying the audience’s sense of self importance.”

This idea of an “invisible monster,” an unseen entity with the ability to inflict fear and terror, has been actualized by the outbreak of coronavirus. “It’s incomprehensible to us [to] a large degree that something microscopic that we can’t see is affecting our society in such a profound way,” Roe muses. Much like the “invisible monster,” we witness in the movies, this pandemic has forced us to acknowledge and come to terms with our own mortality and relative smallness. “[And] that’s what Lovecraftian horror is, right? That’s what cosmic horror is. It’s about bringing your audience face to face with the incomprehensible.” While our situation may seem bleak, Roe reassures us that horror films and COVID-19 have another important thing in common. “By reminding us of our smallness, [cosmic horror] has the power to bring audiences together, to bring people together, and to recognize that we are all similar in probably the most important way:…we’re all very, very, very small.” “And if we can all recognize how small we are,” Roe explains, “then I think we can let go of these rather absurd things that we argue about here on Earth.”

Keep an eye out for James Roe’s newest cosmic horror film, Colossus, to see Roe combine history and science fiction.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

online casino Pin Up https://pin-up-casino666.ru онлайн казино Пин Ап Официальный сайт