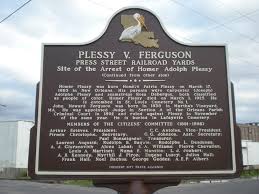

Plessy v Ferguson, at the corner of Press and Royal Street. (Photo: Google)

The public education system in New Orleans is unlike any other city in the country; as of the summer of 2019, the city is entirely dominated by charter schools. This system, taken up in the havoc of sharply declining test-scores post-Katrina, is both a point of pride and contention among parents and educators.

Beyond pride in the choice-based system (rather than being bound by one’s geography), as well as the improving graduation and college matriculation statistics in the years following Katrina, the model still exposes the gaping flaws in how New Orleans educates its children. Forty per cent of the city’s schools are ranked “D” or “F” by state standards (Sernovitz). And the city still faces large hurdles to overcome in terms of segregation; 85% of the school district in 2017 was African American, with the majority of the city’s white students opting to enroll in single-run charter schools or private schools. (Dreilinger).

At the corner of Press and Royal Street, the horns from the passing trains are overbearingly loud and piercing; to put it frankly, to the pedestrian, they are downright obnoxious. This corner is the site that determined the fate of how New Orleans would educate its children. It’s both ironic and poetic, it seems, that it was this particular corner that was selected to be the site of historic importance– the site where, as a result of Homer Plessy’s decision to use the train stop here, stood up to the Louisiana Separate Car Act and led to the chaotic and segregation-enabling “separate but equal” Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson. It’s a corner that’s inherently distracting. It overwhelms ears with a cacophony of blaring train horns that forces one to stop before the tracks and simply deal with the discomfort of noise.

Standing there is unpleasant–but at the corner of Press & Royal, the horns of the train are more than just uncomfortable sounds; they’re a reflection of the uncomfortable parts of our society that were first enabled there. It was a calculated attempt by local black leaders to overturn the newly-implemented laws of segregation on streetcars in New Orleans, but ultimately became a nation-wide green light on Jim Crow laws after being voted down by the Supreme Court (Junne). Much like the sounds of the train, Plessy was conscious of the fact that his actions would be unpleasant and uncomfortable. Their goal was to distract from all other nuances of why these laws may exist to make the point that separation by color is inherently racist and unequal. It was meant to be a blaring siren that makes onlookers and the public compelled to stop and look in their direction (Medley).

Blanket statements are often made about the case, brushed to the corner of history, never to be further looked at or analyzed because of its grim ending and because of the fact that it is overwhelmingly regarded as a failure (Medley). Its outcome led to the path of this site becoming known for nothing but its loud and deafening train horns, never getting its due recognition for the significance of these trains in New Orleans classrooms. Many of the issues with public schools in New Orleans can be traced all the way back to the Jim Crow laws legal condoning of racial separation. During reconstruction, New Orleans developed one of the most thriving black communities, with black citizens often being more educated, and having a relatively high quality of life and acceptance within the community at large. This is largely due to the city’s Spanish and French influences (Taylor), However, as Reconstruction ended and the city experienced more Americanization, much of this feeling of unification receded, ultimately leading to elected officials in the State passing the Separate Car Act. Today, New Orleans ranks 49th of 50 for academic achievement, with these lagging achievements primarily affecting minority communities (Sentell).

Through sounds alone, one can trace some of the forgotten historical importance of the case, what’s been left out of the historical conversation, and what’s not taught in schools. Hearing the mingling of our loud and electric car horns with the conductor’s initiating of the blaring engine of the train by hand is a direct metaphor for the connection of the historical boycott of Plessy with that of Rosa Parks’ famous bus boycott. While to many, the story of Plessy and Ferguson ended with the decision made by the Supreme Court in 1896, quite the opposite is true (Junne). Ten years after the case, a group inspired by the Plessy convened, leading to the creation of the NAACP (National Association of the Advancement of Colored People), the group that led much of the work done in the Civil Rights Movement and weaponized public transportation once again by orchestrating Rosa Parks’ famous defiance to move to the back of a bus in Alabama (The Plessy and Ferguson Foundation). […] As put by the Plessy and Ferguson Organization, “Her historic refusal to sit in the back of a Montgomery, Alabama bus was foreshadowed 59 years before her time by a proud shoemaker from New Orleans. Homer Adolph Plessy, who, with the Citizens’ Committee, challenged the 1890 Separate Car Act of Louisiana on June 7, 1892. In doing so they laid the groundwork for much of the Civil Rights progress that we experience today.” (The Plessy and Ferguson Foundation). As the train slowly rolls down Royal Street, its engine obnoxious and piercing, it blocks the traffic at Press St, causing drivers to honk their horns blocks back — it is their turn to make the noise. It is clear that these noises are subsequent to each other, co-dependent; if it was not for one there would not be another. Plessy and his train have run their course in history, it seems to say. It’s now time to hear Rosa, making herself known with her loud automobile.

New Orleans is a city of historical contradictions; a system of failing schools where once stood a thriving hub of education; a place known for racial and economic inequality that was once admirably integrated. But beyond this education system, beyond a city with a complex of failures, successes and unabashed pride are the train horns; impossible to ignore, loud, but signal hope– even if it’s not clear to us yet.

Sources:

Dreilinger, Danielle. “School Segregation Persists in the New New Orleans, Study Says.” NOLA.com, 4 Apr. 2017, www.nola.com/news/education/article_844f726f-047e-52c1-9292-d0cc9358c867.html.

“History – The Plessy and Ferguson Foundation.” The Plessy and Ferguson Foundation, 29 Apr. 2016, www.plessyandferguson.org/history/.

Junne, George H. “Review: Plessy v. Ferguson: A Brief History with Document by Brooks Thomas, Ed.” Explorations in Ethnic Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, 1997, pp. 122–123., doi:10.1525/esr.1997.20.1.122.

Medley, Keith Weldon. We as Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson. Pelican Pub. Co., 2012.

Sentell, Will. “Louisiana Public Schools Still Struggle in National Rankings; ‘Look at Where We Started’.” The Advocate, 4 Aug. 2019, www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/politics/elections/article_e1ca45a8-b2e5-11e9-a5a6-1b94dfeccfff.html.

Sernovitz, Gary. “What New Orleans Tells Us About the Perils of Putting Schools on the Free Market.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 30 July 2018, www.newyorker.com/business/currency/what-new-orleans-tells-us-about-the-perils-of-putting-schools-on-the-free-market.

Taylor, Michael. “Free People of Color in Louisiana.” LSU Library, lib.lsu.edu/sites/all/files/sc/fpoc/history.html.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.