Under the surface of the New Orleans tourist economy and booze-fueled French-Quarter, there exists a bumping music scene with disco roots, deep bass, and hi-hat patterns known as house. House originated in the club life of ‘70s New York and Chicago, but a budding artist collective made up of New Orleans locals has brought this four-on-the-floor resonating beat to the city’s young-adult party culture. These men are known as The Pink Room Project, co-founded by DJ and artist Keith Cavalier and singer Brandon Ares.

Prior to COVID, The Pink Room Project established a tradition of hosting free social gatherings to promote their sounds. Appropriately, the venue had (you guessed it) pink walls. Originally, these parties were a crafty way to gain an audience, but as they matured, they evolved into a cross-cultural experience where the crowd reflects the musical diversity found in, for example, a 2019 set produced by Cavalier. In this set, Cavalier was able to incorporate songs from Kanye West, Erykah Badu, Khruangbin, Daniel Caesar, and Shakedown, creating a cohesive deep house piece that utilized rap, R&B, soul, and dub. As Cavalier explained in a 2017 VICE article, “the party is the incubator. The music is the fucking culture, the sound.” The turnout of a Pink Room party varied from Mid-City locals to Loyola Marymount students, all with one overarching similarity: their status as young adults exploring the 110 to 130 BPM of house music.

People dancing at a party, not specifically The Pink Room Project. (Photo by: magda s)

In the past three years, house has picked up major traction. A big reason for this spike in popularity is producers like Cavalier and Ares who recognize that people want to slow down, take a step back from the previous dubstep era, but maintain a similar energy. As Cavalier says in an Instagram post, “In spite of today’s culture where everything is microwaved and we want shit to be given to us the second it’s in our brain and rushed to us for consumption, house music makes you wait for it, it makes you sit your ass down and chill.”

For Keith Cavalier, who goes by the artist name Lil Jodeci (an homage to the ‘90s R&B quartet), The Pink Room Project is an opportunity to share his art while showing that, as a Black man, there are infinite avenues to take within music. He explains in an interview with VICE, “we wanted to give not only young people but also Black people a perspective of, you don’t just have to do fucking rap music. You can do house music. You can do dance music.” Black culture has influenced every genre: jazz, blues, rock and roll, and techno, to name a few. The house played at The Pink Room Project emerged from disco, and if you trace the roots of disco, they point you directly to Philadelphia’s R&B scene of the late ‘60s, featuring predominantly Black and Latino musicians. Private dance parties in New York’s underground Black drag ball community were some of the first to embrace disco, channeling the “Rent Parties” of the early 1900s where Black people who migrated to the industrial Northeast would gather, building connections while listening to music. The Pink Room Project is the newest rendition of this alternative party scene, with every aspect rooted in Black culture. Lil Jodeci and Brandon Ares have continued this musical tradition that dates back 100 years, making it modern and accessible to New Orleans. Keith Cavalier understands this legacy he holds, saying in an Instagram post, “you know what I enjoy about dance music, house music in general, it’s foundationally our music.”

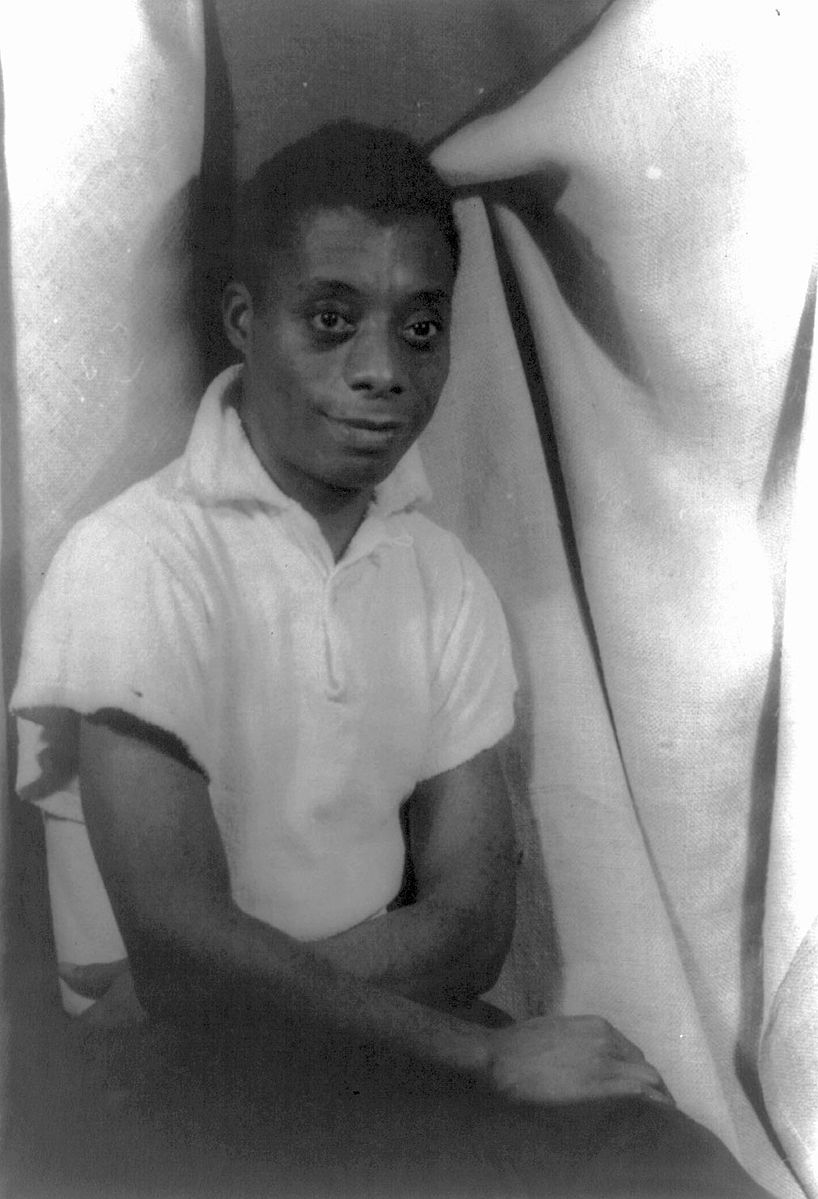

James Baldwin in September 1955.

By the mid-’70s Donna Summer, Gloria Gaynor, and Chic among others were breaking out as popular disco artists. However, disco became mainstream when the Bee Gees’ track “You Should Be Dancing” hit the charts as the number one disco song. Then, in 1977, the release of Saturday Night Fever, a film made up of chiefly white actors, secured the gentrification of disco. As James Baldwin said in his 1979 New York Times piece “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?,” ”I do not know what white Americans would sound like if there had never been any Black people in the United States, but they would not sound the way they sound.” In this work, Baldwin is referring to speech, but his concept applies to a broader phenomenon seen across the spectrum in the United States: white people appropriating Black culture, bringing it out of the alternative and into the mainstream to claim it as their own. As Baldwin explains, “Beat to his socks, which was once the Black’s most total and despairing image of poverty, was transformed into a thing called the Beat Generation, which phenomenon was, largely, composed of uptight, middle-class white people, imitating poverty, trying to get down, to get with it, doing their thing, doing their despairing best to be funky, which we, the Blacks, never dreamed of doing–we were funky, baby, like funk was going out of style.”

The Pink Room Project has reclaimed house, the baby of disco, as Black music birthed by Black culture. Lil Jodeci and Brandon Ares created a space of respect for house where Pink Room fans understand they are being invited into this heritage. The Pink music collective has created crucial room for Black artists to explore their history, bringing it into the future and making it modern. As rapper Delish Da Goddess, who takes advantage of The Pink Room’s space, said in a 2017 VICE interview, “The outlets for Black artists are expanding more and more in New Orleans. We have to keep putting together our own shows and have the mind of an entrepreneur. Never let the white man tell us who we are!”

People enjoying a party, not The Pink Room Project. (Photo credit: magda s)

The Pink Room Project’s success is tangible, attracting famous artists across New Orleans such as Mannie Fresh and Solange, who booked a DJ she met through Pink Room to play her Saint Heron events. Lil Jodeci and Brandon Ares are redefining what it means to be a Black artist in the 21st century. Their initiative is all-inclusive, built on history, love of sound, and connection. Hopefully, once COVID has calmed down in the fall, we will see The Pink Room Project start up again, continuing this 100-year-old legacy of alternative partying.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.