What do you think about when you go to the doctor? For me, a white female, going to the doctor is at best an inconvenience and at worst a source of anxiety and dread. However, for one of my public health professors, going to the doctor could put her or anyone in her family in a potentially dangerous situation.

“Just having an accent causes doctors to treat my parents differently than they would treat a white person,” said Dr. Eva Silvestre.

This differing treatment can vary from not believing BIPOC patients about their pain levels to under-prescribing tests and medications that could mean the difference between life and death. Racially biased medical malpractice dates back to the time of slavery and Jim Crow with many historical examples, such as the cancer cells taken from Henrietta Lacks, forced sterilization, and the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments.

What happened in Tuskegee was a particularly horrific example of racial malpractice because the study participants were one, not told they had syphilis, two, given fake “treatment” which was really just aspirin to relieve their pain, and three, by the end of the study, an effective treatment for syphilis had been approved and was available. However, it’s all of these historical examples along with daily personal experiences with medical professionals that have planted a deep seed of mistrust between the medical system in the Black community.

“There are a lot more recent examples than Tuskegee that make Black people unwilling to go to the doctor though,” said Dr. Silvestre. “It’s what happened to their mother last week. That’s why they don’t trust the medical system.”

In fact, a study done in 2016 found that white doctors were more likely to think Black patients were exaggerating their pain levels compared to white patients (Schäfer et al. 1620). This disparity was worse for Black women than Black men, which is reflected in the disproportionately high maternal mortality and morbidity rates among Black women in America compared to white women. This study also found that when doctors didn’t believe a BIPOC patient’s reported pain levels, they were more likely to prescribe milder forms of treatment or recommend home remedies (Schäfer et al. 1622).

Then, another 2016 study by the Journal of Urban Health found that Black Americans were more likely to only visit the emergency room for extreme pain versus regularly seeing a primary care doctor (Arnett et al. 458). While part of this disparity can be attributed to lower rates of insurance and health literacy among minority populations, many Black people surveyed ranked “mistrust” as a primary reason for not visiting a doctor regularly (Arnett et al. 460).

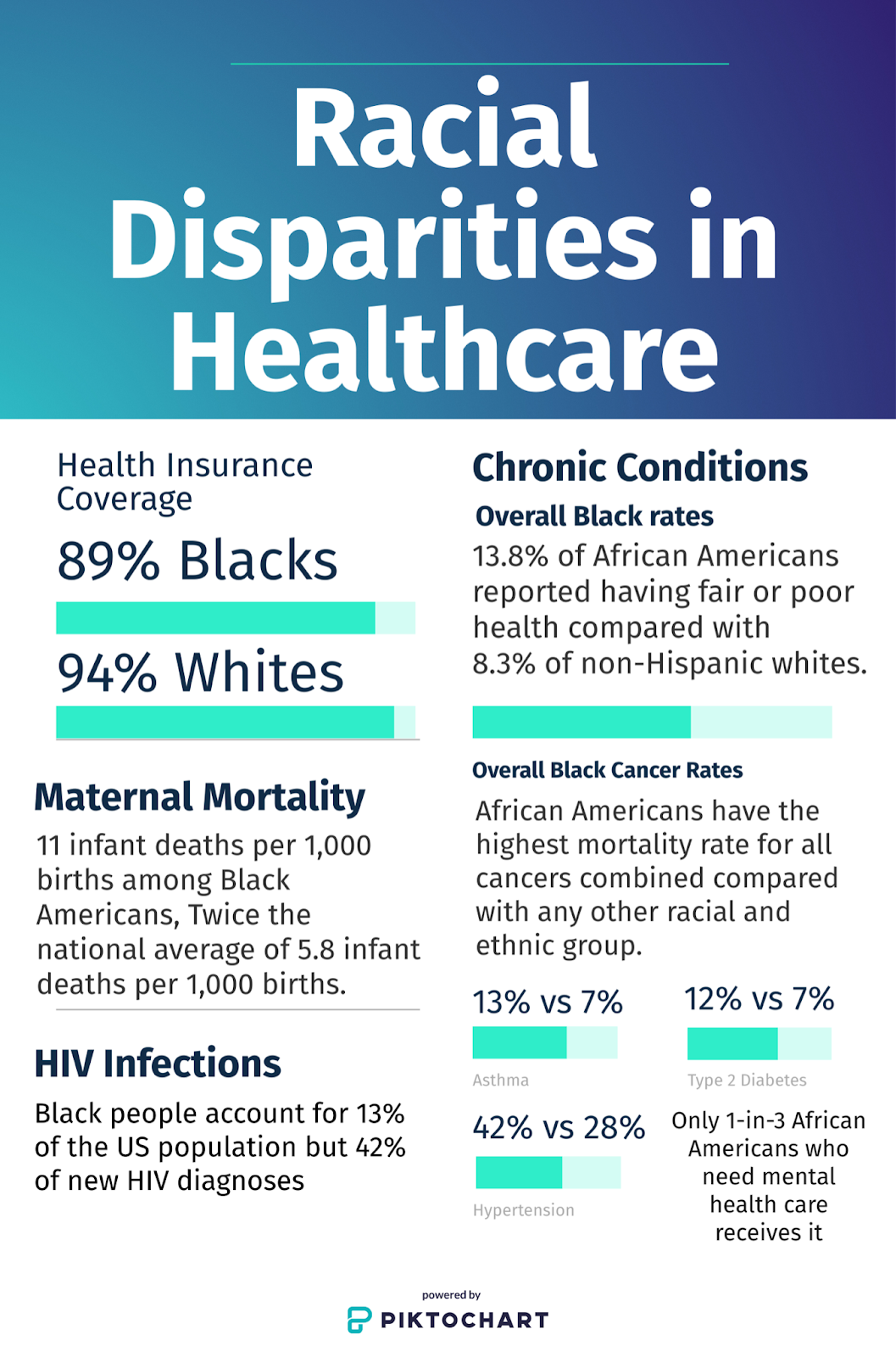

Racial Disparities in Healthcare

Dr. Silvestre knows the reality of these statistics all too well. Her mother passed away from a heart attack in 2019 after a doctor waited for over two years to order a stint test that could have saved her life.

“She had not been feeling well for years, and all they did was give her an antidepressant until she finally switched cardiologists…after her stint test, she never left the hospital,” said Dr. Silvestre. “I still blame that cardiologist.”

Personally, I’m lucky enough to have never worried that my doctor won’t believe me when I tell them about my concerns or that my doctor would think differently of me based on where I come from or what I look like.

As a public health major, I’ve been learning about health disparities ever since my first “Intro to Public Health” 1010 class. In fact, one of my most passionate professors often proclaims that the field of public health has become a study of health disparities, why they occur, and what we as public health practitioners can do to fix them. However, my privilege as a white person has spared me from the microaggressions and blatant racism that my BIPOC peers have had to face their entire lives. Therefore, when I got the chance to do a project on a health-related societal issue, I knew I wanted to document and share the history of racism in healthcare and how that has presented major barriers to many of society’s most vulnerable.

From higher rates of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cancer to STDs, Black and Latino Americas suffer more than white Americans. Dr. Elizabeth Glecker is especially passionate about the disturbingly high rates of maternal mortality among Black women in New Orleans.

“It’s an absolute disgrace. Just look at the numbers!” she often proclaims.

And she’s right. According to a 2018 Louisiana state review of maternal mortality deaths, between 2011 and 2016, Black women were 4.1 times as likely as white women to die while pregnant or within 42 days of childbirth from complications like blood loss, cardiomyopathy, and heart disease. At the time, the state also said 45% of all pregnancy-related deaths were preventable.

So how do we address this problem?

“It’s a system-wide approach, starting what we’re taught in schools,” said Dr. Silvestre.

Dr. Gleckler agreed to say, “We are taught how to point a finger at someone and blame them for their situation instead of looking at the structure that got them there in the first place.”

With comprehensive training, bystander interventions, and increasing the diversity of healthcare providers, we may start to close the gap between the health outcomes of BIPOC patients and white patients. It will take time and some discomfort, but together, we can make healthcare more equitable and accessible for all.

Resources to learn more:

Sources:

Arnett, M. J., et al. “Race, Medical Mistrust, and Segregation in Primary Care as Usual Source of Care: Findings from the Exploring Health Disparities in Integrated Communities Study.” Journal of Urban Health, vol. 93, no. 3, 2016, pp. 456–467., doi:10.1007/s11524-016-0054-9.

Bakhshaie, Jafar, et al. “Perceived Racial Discrimination and Pain Intensity/Disability Among Economically Disadvantaged Latinos in a Federally Qualified Health Center: The Role of Anxiety Sensitivity.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, vol. 21, no. 1, 2018, pp. 21–29. Crossref, doi:10.1007/s10903-018-0715-8.

Hagiwara, Nao, et al. “Detecting Implicit Racial Bias in Provider Communication Behaviors to Reduce Disparities in Healthcare: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Directions for Provider Communication Training.” Patient Education and Counseling, vol. 102, no. 9, 2019, pp. 1738–43. Crossref, doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.04.023.

Henderson, Saras, et al. “Cultural Competence in Healthcare in the Community: A Concept Analysis.” Health & Social Care in the Community, vol. 26, no. 4, 2018, pp. 590–603., doi:10.1111/hsc.12556.

Nao Hagiwara, Jennifer Elston Lafata, Briana Mezuk, Scott R. Vrana, Michael D. Fetters, Detecting implicit racial bias in provider communication behaviors to reduce disparities in healthcare: Challenges, solutions, and future directions for provider communication training, Patient Education and Counseling, Volume 102, Issue 9, 2019, Pages 1738-1743, ISSN 0738-3991,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.04.023.

Schäfer, Gráinne, et al. “Health Care Providers’ Judgments in Chronic Pain: the Influence of Gender and Trustworthiness.” Pain, vol. 157, no. 8, 2016, pp. 1618–1625., doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000536.

Woodgate, Roberta Lynn, et al. “A Qualitative Study on African Immigrant and Refugee Families’ Experiences of Accessing Primary Health Care Services in Manitoba, Canada: It’s Not Easy!” International Journal for Equity in Health, vol. 16, no. 1, 2017, doi:10.1186/s12939-016-0510-x.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.