Editor’s Note: In 2020 (and 2021), there have been a lot of unanswered questions about life and living, so in our partnership with the Chemical Engineering Service Learning Class at Tulane University, taught by Dr. Julie Albert, we made it our aim to find questions we could answer. The series is called “Dear Big Chem-EZ” (think “Dear Abbey” but with less about “Why does my partner ignore me?” and more about “Can I actually drink my tap water?” and “What’s that smell outside my house?”).

You can look for new pieces every day this week and next because we love science, we love answers, and we love it when our streets don’t flood! Let’s take a look at the drainage system in NOLA! If you have questions you’d like answered, send them to thebigchemez@gmail.com.

Dear Big Chem-EZ,

Can you provide some insight into the drainage issues around the city, like which neighborhoods are due for pipe system updates and who is responsible for these updates?

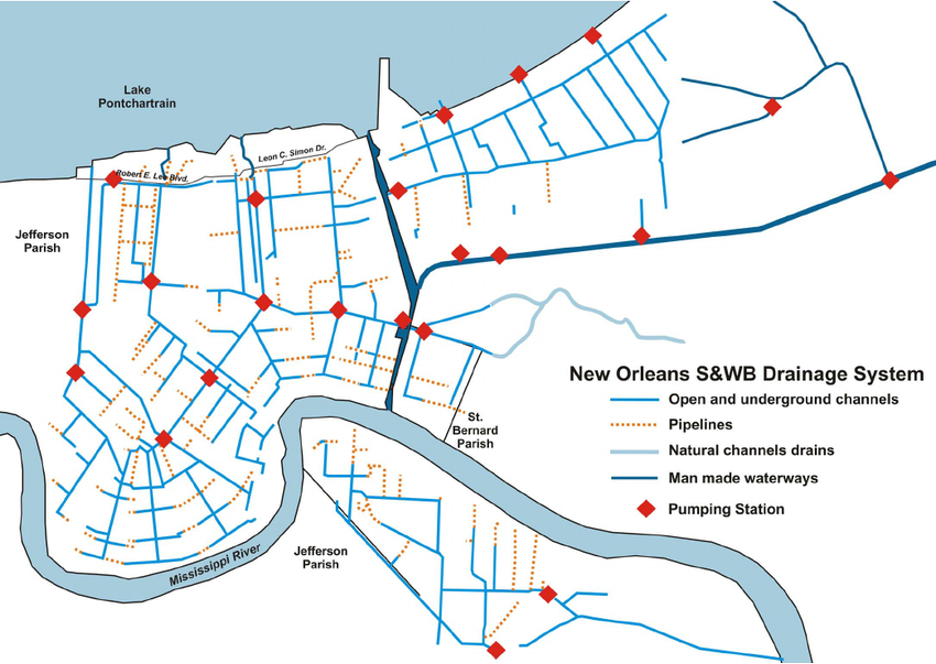

Map showing municipal drainage system operated by New Orleans Sewerage & Water Board. David J. Rogers, “Development of the New Orleans Flood Protection System prior to Hurricane Katrina” (2008)

There is no easy solution to the drainage issues in the city (this NOLA IG account alone will make you cry from laughter and terror), so I’ll first provide some background as to how the system was designed and how it has changed.

The drainage system was designed over a hundred years ago, at the start of the 20th century, so naturally, some degradation has occurred in the system and the water-logged ground it sits in. There are, however, several more factors that play into the poor drainage that so often causes flooding around the city. The system is mainly operated by the entity known as the Sewerage and Water Board (S&WB). The S&WB system consists of 1,500 miles of lateral underground drainage pipes, 200 miles of open and underground canals, over 68,000 catch basins, and 120 pumps housed in 24 drainage pump stations (DPS). Of these 120 pumps, 51 run on an older frequency of electricity.

While the Sewerage and Water Board claims it is able to produce more than enough power via steam turbine generators, it can be expected the pumps have lost some of their capacity over the past century. When it was built, it was estimated that a half an inch of water could be moved every hour after rain fills the underground piping systems.

Today it is estimated that an inch can be moved in the first hour and a half an inch more can be moved every hour. As of 2017, it is estimated that the pumping system can pump water out of the city at a rate of over 45,000 cubic feet (1,300 m3) per second. Even with these supposed improvements, to the residents of the New Orleans, the issue of flooding seems worse than ever. Aside from degenerating pump capacity, a major issue lies in the design of the drainage system.

The pumps cannot be activated until storm water reaches them by gravity. This means that heavy, concentrated rain events can quickly overwhelm a pump, or several, in your local area. Rain events such as these are highly likely even outside of hurricane season, so this is a common occurrence. In addition to the delayed reaction of the system, the pumps are different sizes, serve different purposes, and thus cannot all run at the same time. Of the 120 pumps, only 99 are used for storm water drainage [1]. Often times there can be even fewer pumps available when a rain event occurs if some pumps are being serviced.

With so many factors playing into the cause of flooding, it can be difficult to determine how your neighborhood is being affected. It is important to maintain communication with the entities that manage the drainage system, not only to hold those responsible for the upkeep of the system accountable, but to gain a better understanding of how management of the drainage system can affect your future in the community. The entity responsible for large drainage system update projects is the Army Corps of Engineers. The Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority Board (CPRA) serves as the Non-Federal Sponsor and S&WB serves as the local partner that provides support needed to the project. In conjunction, these entities govern the Southeast Louisiana Urban Flood Control Program (SELA).

The purpose of SELA is to provide improved drainage and rainfall flood relief to Jefferson, Orleans and St. Tammany parishes. On-going projects include the Florida Avenue Phase 2-3, and Phase 4, and the Algiers Area – General De Gaulle Canal. The Corps of Engineers SELA Urban Flood Control project webpage has a total project map and shows the location, description, and progression of ongoing projects. The page also lists contact information for the Corps. I highly encourage those with concerns about their neighborhood drainage and the general well-being of the city to reach out.

-Big Chem-EZ

Resources:

[1] Sewerage and Water Board, Stormwater Drainage System Facts, April 20, 2020.

https://www.swbno.org/Stormwater/Facts

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.