Editor’s Note: It’s back to school week for many, and while experienced teachers are gearing up for a new year, there are new teachers that have no idea what to expect. Yet, this isn’t just because of Covid-19. The creative beliefs and positive views of what a school can be when a teacher is going through training often get crushed when they enter the classrooms of New Orleans. Writer Jessica Stampfer had this experience, and she also has a solution: how we treat the teachers will greatly affect how they treat their jobs.

Photo of students in a New Orleans charter school (Photo by: Getty Images)

Walking into a New Orleans charter school classroom, everything I thought I knew about school changed. When I entered the classroom, thirty five eight-year-old faces were staring right at me — some smiling more than others. I had been assigned to help the teacher manage this large class of, who the school considered, “troublemakers.” Before the teacher began the formal lesson, she had already sent three kids out of the room for their rowdy behavior. Her quick reaction with little explanation implied that this was not a new routine. I found myself not only wondering why she hadn’t given the students a second chance, but also about the consequences of missing course material. The teacher began handing back tests from the previous week, announcing poor grades as she weaved through the aisles. She told one student, “you better study next time or else you’ll be repeating the third grade next year.”

I tried to control my jaw from dropping as I watched disappointment wash over the child’s face. I couldn’t help but worry about how the public shame and embarrassment affected the child’s self-esteem, confidence, and motivation. The teacher’s announcement of failing grades seemed to serve a purpose other than humiliation; it served as a reminder that if the students could not obtain a “D” or above on standardized tests, the school’s four year initial contract would not be renewed and the school would risk closure. While teachers absorb this pressure to produce good grades for the school, the administration works to maintain its finances in accordance with the LA budgetary act as well as comply with all state and federal laws within its operations. While factors such as the school’s finances and operations are important, ultimately, students’ academic performance is what determines the school’s survival.

When a charter school shuts down, it may turn a child’s six minute commute into an hour commute. Unlike public schools in which children are zoned for school based on neighborhood, charter schools are based on choice, allowing parents to select what charter school they wish to enroll their child in. When a charter school closes, naturally, parents will seek a higher performing school for both the sake of a better education and the hope that they won’t have to uproot their child again soon. Looking around at the students, I wondered how long they’d spent traveling to school that morning. Considering that 41% of New Orleans charter schools earned D’s or F’s that year, I also wondered how many students had recently said goodbye to their friends, teachers, and six minute commutes.

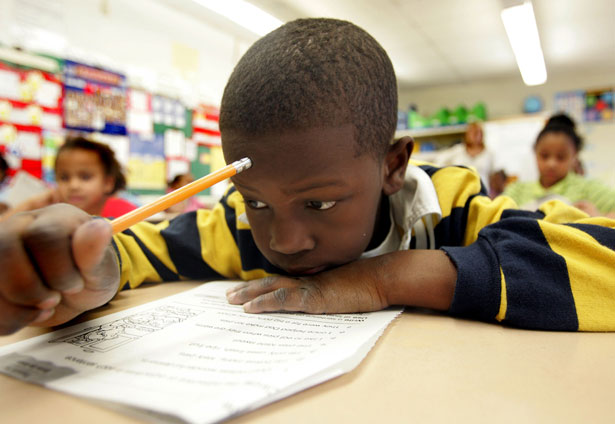

Young student working on an assignment (Photo by: Jose F. Moreno)

After the teacher finished handing back tests she began the lesson for the day: analyzing different types of sound waves. She summoned the class’s attention much like a sergeant does her cadets. The teacher displayed her slides, reading them out loud as she scrolled through. She handed out a double-sided worksheet and allotted twenty minutes of class time for each student to complete it. The teacher suggested students work carefully, as the assignment would be graded. Rowdiness levels rose and any sign of productivity in the classroom ceased to exist.

The teacher demanded silence, threatening to send students to the office where the other three had been sent earlier. A few students began writing diligently, but the rest sought alternative activities: sleeping on their desks, roaming through the aisles, and chatting with their neighbors. And then, two more were sent out. I looked to the teacher for guidance as to how I could help, but she was busy attending to the child with special needs sitting at the desk beside hers. Unfortunately, like many other charter schools, the school didn’t have the means to provide classes for special education students. As I approached a struggling student to help him, I realized that he wanted to complete the assignment, but he just couldn’t read the question. Given that about 40% of New Orleans residents ages sixteen and up have literacy rate levels below that of a fifth grader, I suspected he wasn’t the only one. The student threw his pencil across the room, claiming he didn’t care about the assignment or his grades. I retrieved his pencil, sat down next to him, and read him the question.

In that moment, I saw a spark of excitement as he quickly scribbled down the answer.

He attempted to conceal his grin, but quickly gave in, and I smiled back. As CSEFEL suggests, this interaction would increase his learning confidence and would positively affect his social and emotional development. I began making rounds to the students, reading and interpreting each question as they needed. As we talked through it together, I could see each student’s confidence growing. Most students had finished around the same time the teacher had finished helping the student with special needs. As students placed the assignment on the teacher’s desk, the teacher showed no sign of pride or praise for the students’ accomplishments. Her only expression showed relief knowing that class was almost over. With only two minutes until the bell, the teacher allowed ‘chaos’ to commence for the remainder of class. She sat at her desk and let out a sigh as if she’d just finished a half-marathon. When the bell rang, students scurried out, exchanging no friendly goodbyes with the teacher. “Nice meeting you, see you next week”, I said on my way out the door. Only I wouldn’t.

The teacher began explaining to me that this would be her final week teaching at the school. She’d been working there for about a year and a half, working ten to twelve hours a day and making $44,500 annually. Maybe she’d go teach at a public school instead, she told me, where she could work eight to nine hours a day and make $53,400 annually. However, she worried that only having a bachelor’s degree wouldn’t certify her to teach there as it had for the charter school. She’d figure it out, she told me – and I hoped she would.

As I left the building, I wondered how different the classroom may have looked that day had the teacher been treated more fairly. Perhaps if she had been, she would have stayed, and created a more beneficial classroom environment – one filled with more smiles than sighs. But instead, the students and I would both be introduced to a new sergeant on Monday.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.