Editor’s Note: Nola 2 Angola, which organizes an annual bicycle ride to Angola Prison to support and fund the Cornerstone Builders Bus Project, which connects families to their incarcerated loved ones, is happening October 17-19, 2021. In honor of that organization and the work they do, we’ll be running pieces focused around the prison industrial complex and those trying to fight against it. We’re looking back to the 1840s and Gallatin Street for this piece in order to see the foundation of the system that still exists today.

The French Market, where Gallatin Street and all its debauchery used to be located. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

In the 1840s, more than 1,500 steamships were arriving in New Orleans per year. With people flocking to the port, New Orleans became the fourth-largest city in America, boasting over one hundred thousand inhabitants. The first steamship began chugging between Natchez and New Orleans in 1812, providing Southern farmers with access to faster transportation of their main crop, cotton. Steamboats and cotton became integral components of the New Orleans economy during this era. Moreover, the necessity to harvest cotton for economic means led the practices of slavery and racism to be deeply woven into the fabric of New Orleans society. Preoccupation with slavery and the steamboat industry during this time led to neglect of crime in the city, specifically in the area near the dock known as Gallatin Street.

Gallatin Street was a two-block area near the Mississippi River port and French Quarter during the 1800s when the steamship industry was crucial to the New Orleans economy, making Gallatin’s rowdy nightlife, which attracted sailors, a vital component of the economy as well. During this time, criminals, prostitutes, and gangs alike gathered on Gallatin Street to engage in illegal ventures and participate in the New Orleans black market of crime. Sitting right near the levee on the Mississippi, the location of Gallatin made it ideal for drunken sailors to enjoy the rowdy and promiscuous entertainment and find housing near the port. The busy Port of New Orleans kept Gallatin bustling with new women and traveling men for its boarding houses and brothels, where drinking, sex, and crime were the standard. The levee also provided ample work opportunities on the many steamboats that came in and out of the port, acting as an economic center for New Orleans. The nightlife near the dock persuaded workers and sailors to want to come back, thus serving as a stimulus for the port and the economy.

Purposeful neglect of the crime on Gallatin served those in power, specifically the wealthy, White elite and sometimes the police themselves. The violent crime on Gallatin Street, though widely known, was largely avoided by New Orleans police. The police often bypassed the area at night or when they were working the city alone without a partner. Some of the police that did not avoid the area were actually involved in the crime, and these dirty cops depended on bribery. If the police did attempt to address the crime running rampant in the area, they often targeted people for smaller offenses, such as prostitution, instead of the more violent crimes that occurred on Gallatin. Overall, police negligence in addressing the intense crime demonstrates how Gallatin and primarily middle-class, White crime was overlooked. The New Orleans police did not have proper staffing or funds during the 19th century—and their attention was focused elsewhere.

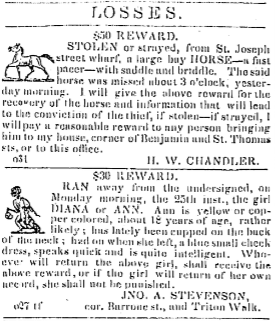

Piece from Times-Picayune archives of November, 1841 (Photo By: Victoria Kutz)

Piece from Times-Picayune archives November, 1841 (Photo By Victoria Kutz)

Sections on crime in the New Orleans Times-Picayune Newspaper from 1841 (back then called The Daily Picayune) focus primarily on runaway slaves or crime related to “negroes” based on racist ideals and the social stratification that resulted from slavery. In the paper, the “losses” section lists runaway slaves in the same column as ads for stolen horses and lost dogs. The slaves were treated as any other property, as the ads offered rewards for the return of their slaves or avoidance of punishment if the slaves returned on their own. In the crime section, the Picayune notes that a “Charles, a negro belonging to Mr. Gurlie, charged before Recorder Bertus with severely cutting the hand of officer Lezuneau will probably be hung (Daily Picayune, 2 Nov. 1841, p. 2).” The racist practice against Black slaves in nonchalantly announcing their execution in the paper for minor offenses displays the strategies of control that White society exerted over slaves and Black New Orleanians during this time in order to stay in power. In the minds of Southern aristocrats and farmers, slaves were a necessity to their economy for the growth and production of cotton. By focusing on Black crime, specifically slaves, the media of this era aimed to demonstrate to both Blacks and Whites alike the power of political and social control. The execution, blatantly mentioned above, set an example to other slaves and Blacks in New Orleans, warning them not to step out of line as a means of controlling them for the benefit and profit of the elite. As long as White plantation owners and police could keep Black Americans subjugated as slaves, they maintained both physical and economic control, allowing New Orleans to thrive at the expense of enslaved Americans.

Ads for runaway slaves in the Times-Picayune allowed White farmers to assist each other in returning the “property” to the correct plantation in order to ensure their collective economic success. In a section of the Daily Picayune from November 3rd, 1841 (p. 2) entitled “Important to Slave Owners,” the Picayune writes, “The Sheriff of Feliciann, who returned a few days ago from Kentucky, has communicated to the editor of the Herald some important facts that should be generally known, in order to excite the vigilance of Southern gentlemen traveling on the Mississippi and its tributaries and also enable, in all probability, the owners of valuable runaway slaves to recover their property.” If a White farmer lost a slave during this time, he was most likely losing between 500 to 1000 dollars, depending on the age and skills of the slave. This loss was detrimental, as the plantation owner/buyer of the slave would also lose the potential profit of cotton that the slave would contribute to or harvest, explaining why society and the media viewed slaves as “valuable” property during this era. Since the police force of New Orleans was already stretched thin, the main priority was to track down these slaves—not only to set an example but also to ensure their fellow White man economic success. In this sense, the success of the wealthy elite also benefited the economy of New Orleans as a whole, which would potentially benefit the salaries of local police officers.

The port was the center of economic venture and capital during the 1840s, illustrating the necessity of the rowdy entertainment found on Gallatin Street. In the Picayune issues of the 1840s, entire sections were devoted to the steamboat schedules with multiple columns for “Ships &c” and “Steamboats &c.” A large portion of the newspaper is also dedicated to shipping updates, for example, “According to the Merchant’s Transcript, there are now in this port 62 ships, 7 barques, 24 brigs, and 9 schooners. The number of steamboats is very large (Daily Picayune, 4 Nov. 1841, p. 2.).” The extensive mentioning of the port and updates on the input and output demonstrates how both the media and the economy of New Orleans revolved around the port during this time. With an economy dependent upon the transportation of crops via steamships in the port, the media focused on information related to the steamboats, as citizens wanted to keep up with the progress of the economy for personal gain. Concentrating on the benefits of the steamship industry in the port for economic purposes meant that Gallatin Street could be overlooked in the media and by authorities because of its contribution to the industry in providing entertainment to the workers during their stay.

Piece from Times-Picayune archives of November, 1841 (Photo By: Victoria Kutz)

In addition to scheduling and updates, some of the crime stories were focused on ship-related crimes, demonstrating that the port industry and slavery were at the forefront of American society and focus in New Orleans during this era. A mention in the Daily Picayune from November 1841 notes, “A jury in Cincinnati has given a verdict of $20,000 damages against the steamboat Pilot, which ran into and sunk another (Daily Picayune, 3 Nov. 1841, p. 2).” Sections of the paper noting the sinking of ships as major crimes are largely representative of a city dependent on the port. Moreover, in 1840 the number of steamship arrivals was about 1,573 and freight had increased from 67,560 tons in 1814 to about 537,400 tons. Therefore, the police largely ignored the crime on Gallatin near the dock because the rowdy nightlife was supported by the sailors coming in and out of the port, a critical component of the New Orleans economy. If police took action against sailors and the port workers, it might have kept people from wanting to come back, thus limiting the success of the steamboat industry and New Orleans. Furthermore, dirty cops, such as Lieutenant Legget, who was dismissed from the police force for attempting to cover up a murder on Gallatin Street, were benefitting from the brothels, crime, and gang life. Since some of the law enforcement agents during this time were benefitting from the gangs and illegal activity on Gallatin, there would be no incentive for them to do their job as an officer to eliminate the crime. The dirty cops and focus on the steamboat industry led to both neglect of violent crimes and a concentration on racist practices of tracking down runaway slaves, illuminating that the economy built by shipbuilding and slave plantations served as a principal guiding factor in directing police resources.

The society, culture, and economics of New Orleans revolved around slavery and transportation via steamboats. White dominance via slavery and harsh punishments of the law served to maintain control and preserve the economically advantageous subjugation of colored citizens in the South. Ignoring the rampant crime on Gallatin Street was not accidental, as resources were focused on other areas that exercised dominance and economic gain, such as tracking down runaway slaves. Subjugating slaves and keeping them bound to plantations served to keep White people in control and in an economically advantageous environment, using steamships as a means to further White wealth. The remnants of these practices are still seen today, with countless examples of police brutality targeted at people of color and economic disadvantages for Black Americans and those who did not descend from wealthy, White plantation owners.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.