How can opportunity still happen after incarceration? (Photo: Pexels)

The sentencing project estimates that 70-100 million (one in three) Americans possess some sort of criminal record, a population that in isolation would rank as the 14th largest country in the world ahead of Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. Having even a minor criminal record, such as a misdemeanor or even an arrest without conviction, can mean that the process of getting housing, education, a job, healthcare, and numerous other services and necessities becomes substantially more difficult, oftentimes forcing people back into crime and renewing the cycle of incarceration that has plagued communities across the country.

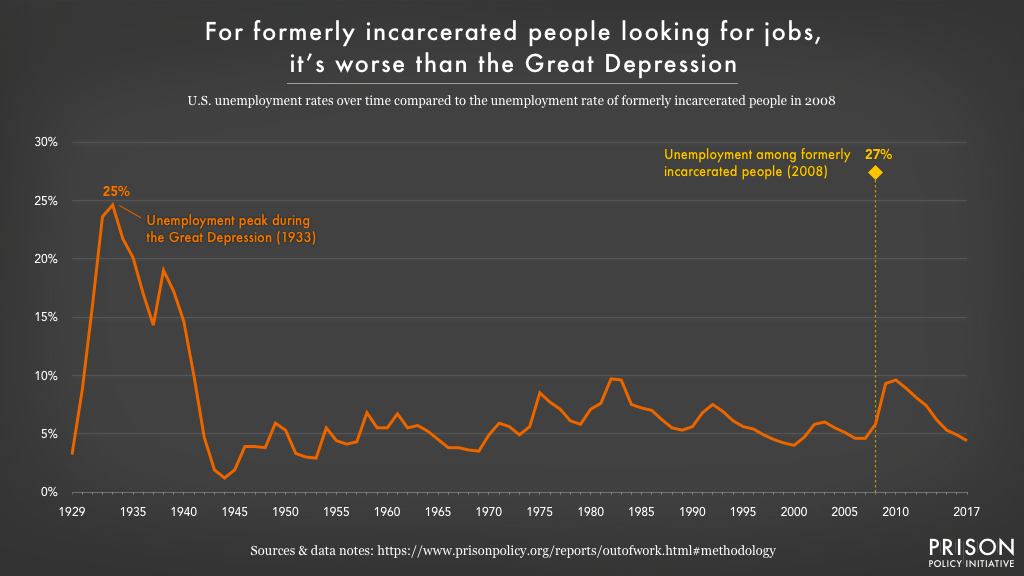

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, the unemployment rate among the formerly incarcerated is 27 percent (the national rate is 5.8 percent), and approximately 25 percent of formerly incarcerated individuals lack a high school diploma GED or college degree. More than 60 percent of formerly incarcerated individuals are unemployed one year after being released, and those who do find jobs take home 40 percent less pay annually. As poverty is the largest contributing factor to recidivism rates, it is no surprise that 43 percent of formerly incarcerated individuals will return to prison at some point in their lifetimes.

Most reentry work, therefore, centers around removing barriers to employment and obtaining education and work experience for formerly incarcerated individuals. Beyond suffering from the prevalence of stringent criminal background checks, the formerly incarcerated are oftentimes locked out of social programs and benefits, a discrepancy that reentry organizations often attempt to compensate for. Additionally, certain programs place a focus on handling the physiological trauma inflicted by years of belittlement and subjugation within the prison system.

“We often say that the first year out is as hard as the first year in,” stated Caroline Sadloski, a lawyer at the Department of Justice who helps run ReNew, a federal reentry program in New Jersey aimed at reducing recidivism rates by assisting those most likely to re-offend. Federal reentry programs such as hers have only gained prominence in recent years as the government begins to shift away from the tough-on-crime attitude and zero-tolerance policies that defined its approach to incarceration throughout the late 20th century as a result of the war on drugs. This attitude shift was distinctly marked by the passing of the First Step Act in early 2020, a landmark piece of legislation for proponents of restorative justice that placed the responsibility of supporting re-entrants upon the federal government itself.

Ultimately, freedom in this country comes with an expectation that one will emerge from prison ready to chart a new “brighter path” for oneself, yet in this regard, the system sets people up for failure. Our social and economic structures amalgamate to what is essentially a “one strike and you’re out” approach to incarceration, as the outlook for those with criminal convictions continues to be bleak long after their sentence has ended. In this manner, any reforms made to sentencing and other aspects of criminal justice will prove far less meaningful as we continue to punish people long after their sentences have expired.

For additional information visit The Prison Policy Initiative’s Website, and for Louisiana-Specific resources visit the Louisiana State Reentry Guide’s website

This piece is part of an on-going series produced in Professor Betsy Weiss’s class, “Punishment and Redemption in the Prison Industrial Complex,” which is taught at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.