Editor’s Note: It’s sometimes called an Odyssey. It’s sometimes called a gift. It’s often called everything in-between, but when we look at life, it feels like a quest. That’s why we’re giving all of April to the Life Quest(ions) that people have always wanted the answers to. Here’s what we did: We asked hundreds of people what quest and question they’ve never been shown or given the answer to even though it’s something they’ve always wanted to pursue. Then, we pursue it and provide the answers! Next up, we’re looking at meditation and the mind.

Day to day, I constantly move from one activity to the next: class, homework, internship hunting. In these moments, I spend a lot of time worrying about how I will fit it all into 24 hours and if I have the energy to do that. I feel as though I exist as a cloud of pure worry rather than a human being. I’m not alone in my worry since 59% of Americans find it extremely difficult to balance work and their personal schedules. That’s not to say that I don’t have my personal schedule. I socialize with friends, go to the gym (sometimes), play video games, cook, make music with my friends: normal college student activities. However, I’ve consistently wondered in my life how I can reduce myself from this inanimate cloud of worry back to a human being.

During our drive down to school this semester, my girlfriend and I binge watched a Netflix series called Explained: a series of 20-minute documentaries each focusing on something specific. One of these episodes I watched was called “Mindfulness.” I had seen this one before and hadn’t thought much about it, but rewatched it because my girlfriend had never seen it. After watching it a second time I gained a new perspective on what meditation is. Mindfulness (a type of meditation) is “a process of bringing a certain quality of attention to moment-by-moment experience.” It’s an ancient philosophy, believed to be practiced as early as 3000 BCE. In the episode, the basic concept of meditation is introduced; to sit upright and maintain focus on something. Most commonly, this is the feeling of breathing. Inevitably, the mind wanders to something else. When this happens, the person should not become judgmental about this lack of focus but simply acknowledge it and return the focus to the breath. There is no need to think about the implications or additional meanings of what the mind wanders to.

During our drive down to school this semester, my girlfriend and I binge watched a Netflix series called Explained: a series of 20-minute documentaries each focusing on something specific. One of these episodes I watched was called “Mindfulness.” I had seen this one before and hadn’t thought much about it, but rewatched it because my girlfriend had never seen it. After watching it a second time I gained a new perspective on what meditation is. Mindfulness (a type of meditation) is “a process of bringing a certain quality of attention to moment-by-moment experience.” It’s an ancient philosophy, believed to be practiced as early as 3000 BCE. In the episode, the basic concept of meditation is introduced; to sit upright and maintain focus on something. Most commonly, this is the feeling of breathing. Inevitably, the mind wanders to something else. When this happens, the person should not become judgmental about this lack of focus but simply acknowledge it and return the focus to the breath. There is no need to think about the implications or additional meanings of what the mind wanders to.

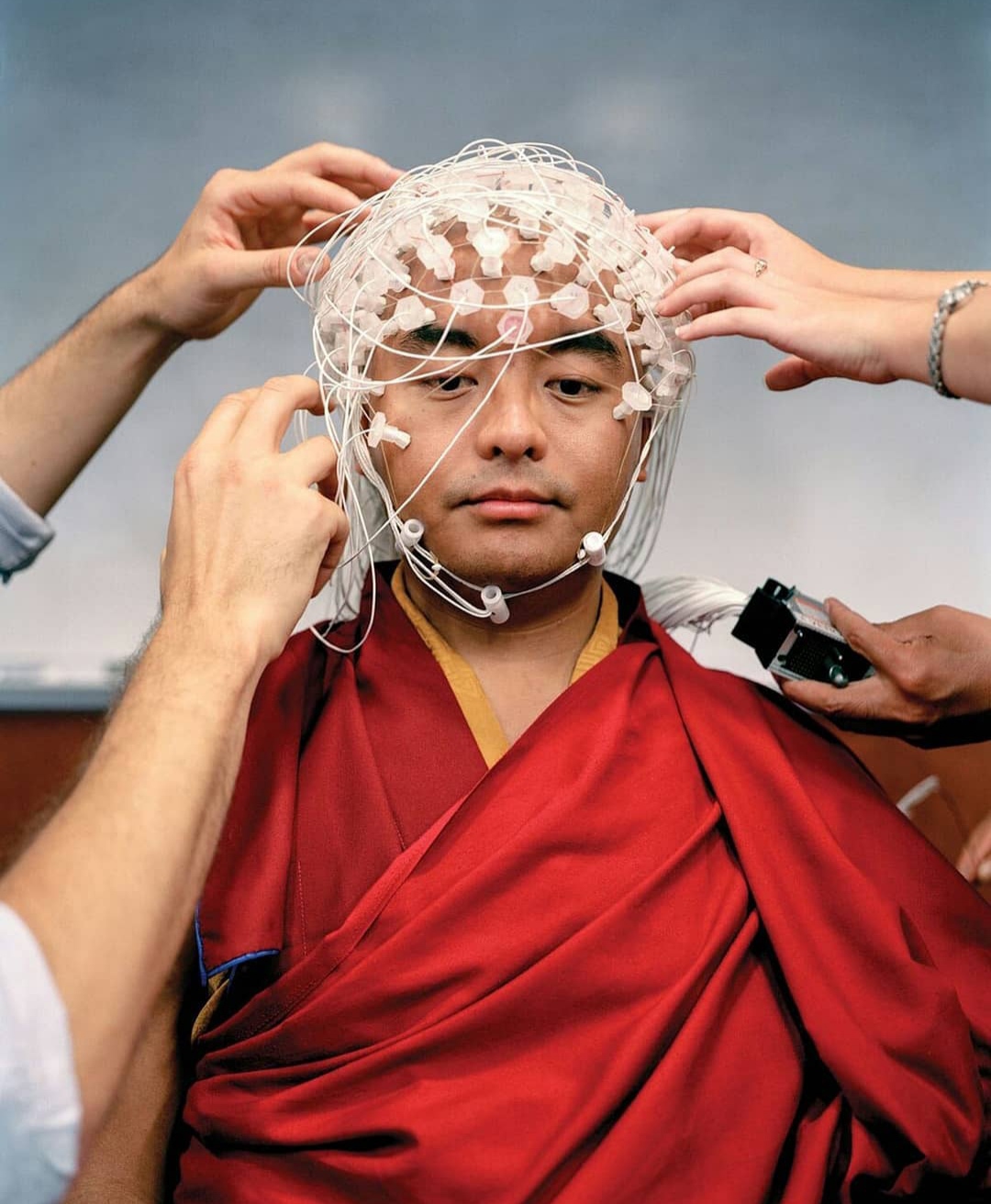

Scientists studying Mingyur Rinpoche’s brain. (Photo by Sonam Lama via Flickr)

During the episode, these concepts are all being taught by Mingyur Rinpoche, a Buddhist monk and the author of many books such as The Joy of Living: Unlocking the Secret and Science of Happiness. Since he began studying Buddhism from age nine, he was able to oversee the Sherab Ling Monastery and even construct the Tergar Monastery in Bodh Gaya. Scientists at the University of Wisconsin found that even though Rinpoche was 41, he had the brain of a 33-year-old. This is no doubt due to his lifelong study of meditation. I felt that I related to the panic attacks he had as a child. His father, who helped him begin his study of Buddhism, told him not to fight the panic. “Why would you not fight panic?” was my initial reaction. It seems intuitive to fight negative emotions and embrace positive ones. However, fighting or avoiding these emotions often backfire. Rinpoche listened to his father and used his panic as support for his meditation. In doing so, he and his panic became “great friends.”

Fast forward into the semester, I naturally find myself stressed out. In these moments of worry, I try to take Rinpoche’s advice. I breathe. Still with no understanding of what using panic as “support for meditation” really meant. I breathe. I focus on the feeling of panic. An uncountable number of thoughts, heart pounding as hard as it can on my ribcage, nausea filling my entire body, pins and needles down to my pinkies and up to the back of my scalp. I realize that the struggle of avoiding these feelings is the true source of unpleasantness. Trying to become a human being instead of this cloud is an impossible task. How can I possibly force myself to become at peace in this state? It’s a far more complex feeling than simply taking deep breaths. However, truly feeling these feelings without fighting them changes how they affect me. Eventually, I feel panic and acceptance of panic, again and again until I end up with just accepting panic which is universal. Many studies have found decreased levels of anxiety after subjects participated in mindfulness-based therapy.

Tergar monastery (Photo by Ricardo Santanna via Flickr)

Rinpoche tells a similar story of finding peace when he speaks about his time wandering the mountains of the Himalayas. Toward the beginning of his journey, he became very sick with vomiting and diarrhea; he was convinced he was going to die. I thought of myself in this situation. At a minimum I would be in full out panic. He had no access to healthcare; it was simply him out in the wild. He felt that if he were to die in that moment, “No problem.” Studies have found that on average people that practice mediation respond less negatively to negative situations. Rinpoche didn’t feel any fear. He described this moment as “los[ing] touch with [his] physical body altogether” but his “mind was clear.” Ultimately, worrying about it wouldn’t change his body’s response to an infection. For someone who has practiced mindfulness as much as he has, this realization was instant. At a certain point he decided that this was no time to die and got up to get water but passed out. He woke up the next day at a clinic and recovered.

Himalayan Mountains (Photo by Ashok Sharma via Pexels)

I try to take this lesson with me when I feel as though I am hopeless out in the wild. The source of this feeling could be from anything or nothing. My mind’s secondary response if it decides to not panic, is to shut down. This is not a peaceful type of shut down like Mingyur’s story. I am paralyzed in every sense of the word. My body is still, my emotions flatline, my thoughts can’t escape their current pattern. Deep down I know I can’t remain like this forever. I feel the instinct to try to approach the feelings of hopelessness and sadness the same way I do to panic. But this is even harder to convince myself to do. I know that I can at least try to focus on the feeling of breathing.

“But why bother?”

“Why wouldn’t I want to escape this state?”

“This won’t change anything.”

“I have to at least try.”

“But…………”

This simple conversation turns into a screaming match. Back and forth, back and forth. The room becomes a mess; words fill the room until there is no more space left, no more room to breathe. With nowhere else to go, words flow out the front door and turn into their physical form. I speak. I breathe.

A wave of relief washes over me. I quickly realize the thoughts of hopelessness and self-doubt aren’t really me. Suddenly it’s so clear: How could I be an inanimate cloud of worry or hopelessness? I’m so obviously a human being.

I wish I could say this happened every time. But I am just starting to learn how to allow this cloud to pass.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.