Editors Note: The following is a five-piece series called “The Truth about the Big Easy” curated by Parker Kim. This series is in partnership with Via Nola Vie and aims to give transplants and locals a series look at what is happening in our local government.

New Orleans always seems to be being left out of the national conversation. Whenever New Orleans is being mentioned it is either about a natural disaster or a report on the rampant partying going on on Bourbon. Sometimes we forget that there is so much more happening behind the scenes in our city. The floats this year at Krewe De Veux were a clear indication that there is more going on behind the curtain in the New Orleans government. From public education to infrastructure this series of articles will give you a better indication of the current state of this great city. There are so many questions that need to be answered and hopefully, this series of articles opens the curtain to why things are the way they are here maybe just a little bit.

Protesters in New Orleans march down Convention Center Blvd ahead of President Trump’s arrival January 14, 2019. (Photo: Nora Daniels)

January 14, 2019

President Trump visits New Orleans to speak at the American Farm Bureau Federation’s annual meeting

10:05 am: I board the streetcar at Canal at Murat. The cold, damp morning was my first time riding one. I find a seat next to a older black woman wearing a gold-tinged scarf over her hair and listen to a mother on my left speak Spanish to her young son. “Mornin’,” the scarf woman says in that buttery way only New Orleanians do.

10:10 am: The crowd packing the streetcar is like most parts of New Orleans—diverse. Nobody holding signs for the protest, though. My previous life in Northeast comes to mind several times as we chugged down Canal: if we were in Boston right now, I thought, this car would be overflowing with well-meaning white people who could afford to take time off from work to bring their family to another protest, their signs poking each other in the eye as they jet towards Boston Common. Black and brown people? There wouldn’t be as many.

10:15 am: Did you know the RTA is actually owned by a French company called Transdev? How ironic is it that: one, they’re a French company; two, New Orleans streetcar operators wear reflective yellow safety vests reminiscent of the recent yellow-vest movement in France; and three, this neon-clad conductor, working for a non-American company, is transporting me to a protest where people are speaking out against the Trump administration’s immigration policies, which work to bar people from the Global South—black and brown people—and elsewhere from stepping a foot in the U.S.? Pretty ironic.

10:25 am: More coincidences. We pass the Department of Veterans Affairs on the right; the slate-colored, mirrored building brings to mind those steel slats the President keeps talking about. You know: it’s not a wall, it’s going to be steel slats. A few blocks down from the VA building is the University Medical Center, outside of which is a huge gold sculpture of people standing on top of each other, their hands interlocked in a moment of interdependence. I looked the statue up later: it’s called “We Stand on the Shoulders of Those Who Came Before Us” and it was made by two artists from Tuscon. After the statue arrived in February of last year, NOLA.com | The Times Picayune writer Doug MacCash wrote that one of the statue’s creators said the statue’s “15 8-foot-tall figures of various body types are meant to imply the diversity and interdependence of mankind,” and “the sculpture should, in part, recall the role of the old Charity Hospital serving New Orleans’ poor.”

Protests in New Orleans, January 14, 2019. (Photo: Nora Daniels)

10:30 am: The woman next to me shifts in her seat, and I get a quick look at what she’s carrying in her large clear plastic cosmetic bag. It’s not cosmetics. A language I don’t recognize is written on some lined paper. Vietnamese? Wait, is she Vietnamese, not African American? I realize I’ve only seen her from the side this whole time.

10:32 am: I don’t find out for sure whether Lillian is part Vietnamese, or just speaks Vietnamese, or if the language was actually Vietnamese at all, but I do learn that she’s from New Orleans, and she lived in New York for four years. We start talking after Lillian remarked about how cold it was. When I say the weekend was supposed to be in the seventies, Lillian replied in a soft voice I had to lean in to hear, “They say New Orleans is the only place where you can have all the seasons in one week.”

Lillian owns property and she, like so many people who grew up here, seems surprised when I tell her I moved here because of the people. I suggest maybe she doesn’t see it as much because she’s gotten used to the fantasticalness of New Orleanians over the years, but she doesn’t think that’s it and actually neither do I.

10:36 am: I get off the street car at Canal at Convention Center and walk briskly towards the cluster of people gathered on the corner across from Harrah’s. People of all ages and races are bundled up in hats and scarves. Several people wear bright yellow vests—not Transdev ones, but ones that look very similar. I learn a few minutes later that the protesters here are wearing them in solidarity with the yellow vests in France.

Next to a woman wearing a beanie and oversized blazer, who leans cooly against a pole in a jaded sort of stance that suggested she’d either helped organize the event or else had been going to similar ones for years, a middle-aged black man clad in one of the yellow vests speaks into a megaphone. “So, the people here in New Orleans, right, and people of color, the company been shut down for us, we’re lacking opportunities.” He points to the sky behind the crowd. “If you guys would just turn around and look at the sky right there at what’s coming up right here, this building that’s being constructed. Local people in this city have been denied the privilege of work. So it’s shut down for them. This is a simple opportunity to take care of their family. This is another barrier that’s trying to separate people. We understand the meaning of shutdown. And we ain’t gonna take it no more. It affects us all. It affects us all, man.”

Protesters in New Orleans. (Photo: Nora Daniels)

10:40 am: More signs start appearing, bobbing above hoodies, and skullcaps. Several have a distinctive New Orleans flavor to them: “Impeach dat”; “YES to disaster relief, NO to the wall, Shut down Trump”; “Migrant workers feed Louisiana.” The letters of one sign are made out of Mardi Gras beads, the purple, green, and gold balls spelling out “SHOW ME YOUR TAXES.” As I dodge through the crowd to get a closer look at a sweatshirt emblazoned with a sparkling beaded portrait of Barak Obama, another man took the megaphone: “It’s becoming to where either you got it, or you’re at the bottom. Those in the middle, they’re pushing you towards the bottom.”

A minute or so later, as the crowd grows larger still, the voice of the same man increases by a few octaves as he asks, “What that called? How you gonna make them work and not pay them?” Several scattered voices yell back, “SLAVERY.”

10:45 am: My hands start cramping up from the cold. Just as I was thinking about how glad I was for putting on two pairs of socks and finding a set of gloves from up North in my car before I left the house, a man in an orange vest and a surgical mask around the top of his head takes the megaphone and began speaking in Spanish. I don’t understand a word he said, but I do understand the passion in his voice, and that the risk he may take by leaving work and speaking out in Spanish is far wider and deeper than a pair of socks.

I dart up some stairs to get a better shot of the crowd and see a young woman in an orange vest and a hat consoling a softly crying toddler. She’s holding a sign and looks proud of it as I catch her eye. The little boy manages to shush as I take a photo of the pair with their sign: “Government Shut [arrow] Don’t Just Hurt Government…It Hurts People!!!!” The woman smiles gently, genuinely, as she clutches the canary yellow caution tape bordering the sign.

Protesters in New Orleans (Photo: Nora Daniels)

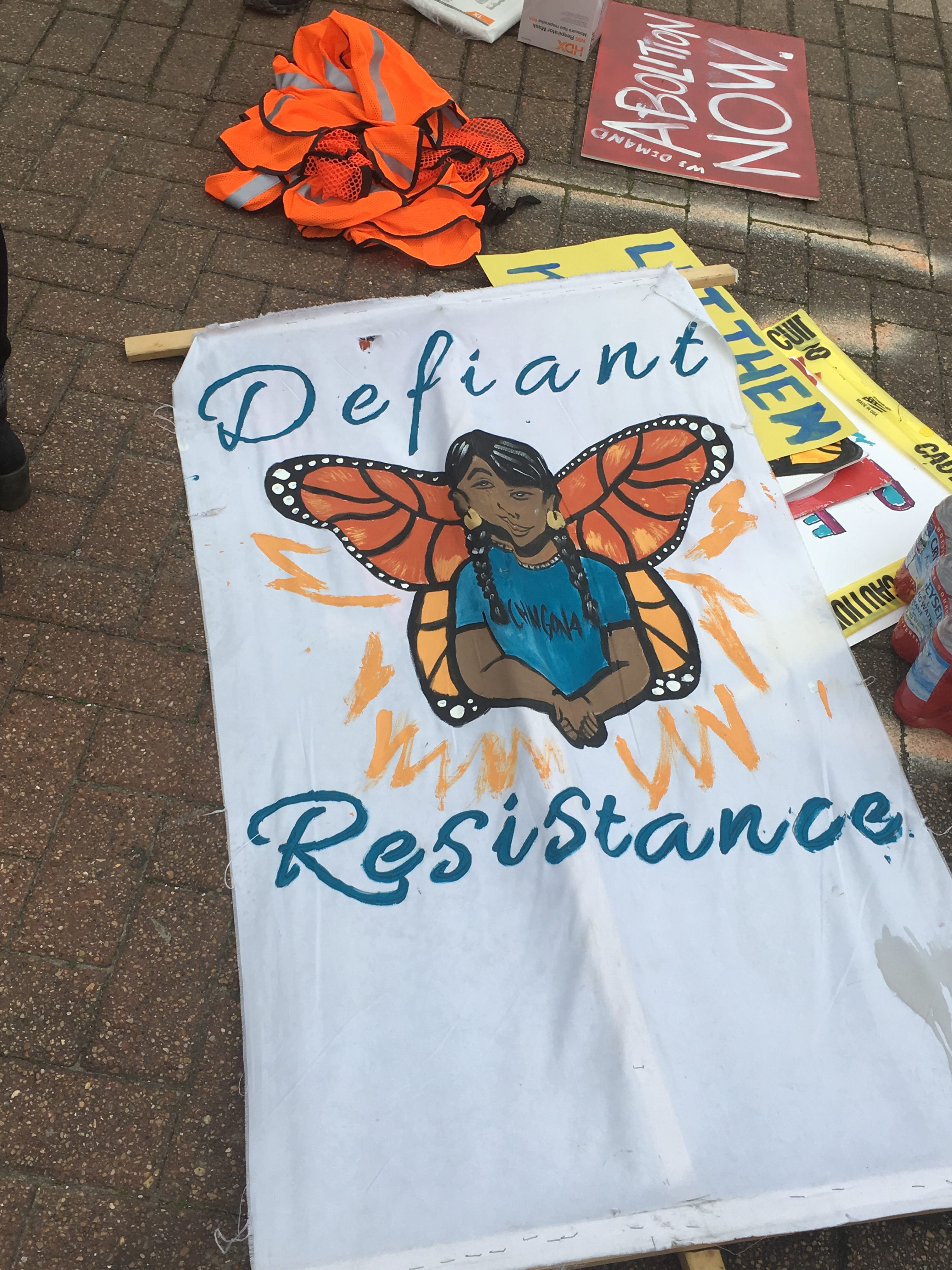

10:50 am: The most brightly colored signs are big banners laid on the ground near the street. They’re beautifully painted in tropical colors, a welcome burst on an overcast day. “ABOLISH ICE,” one reads. Another: “STOP THE RAIDS AND DEPORTATION.” One banner is adhered to a wooden pole for the march happening later. Painted right in the middle is a Latinx girl with braids and butterfly wings, in between the words “Defiant Resistance.” Butterflies are the emblem of migration, did you know?

Protest signs in New Orleans (Photo: Nora Daniels)

10:53 am: The speakers move up to where I was standing. Someone calls: “Who dat said we gonna stop that Trump?” The crowd responds right away: “We dat! WE DAT!”

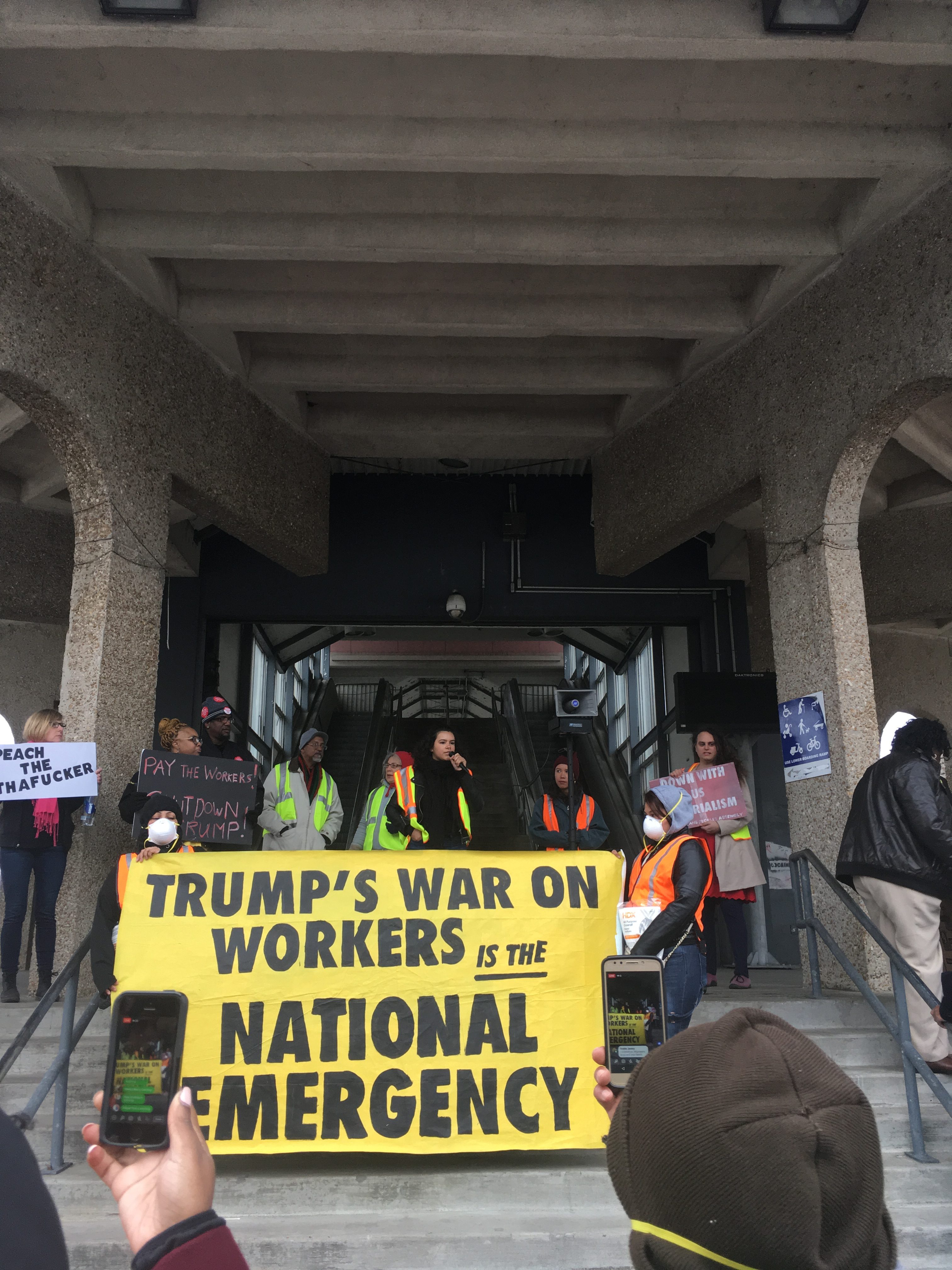

10:54 am: A young woman in a hijab takes the megaphone to speak about white supremacy and capitalism from behind a yellow banner that reads “Trump’s War on Workers is the National Emergency.”

“This is social Darwinism,” she shouted. “They’ve started deport[ing] Vietnamese refugees. We are in New Orleans, with a large Vietnamese population. For the war that WE started, and many years later we are talking about getting rid of Vietnamese refugees. This is not just about Muslims, this is not just about Latinos. Now [it] is about the working class.” She pauses and hands the megaphone to the Spanish translator standing next to her.

Protesters in New Orleans (Photo: Nora Daniels)

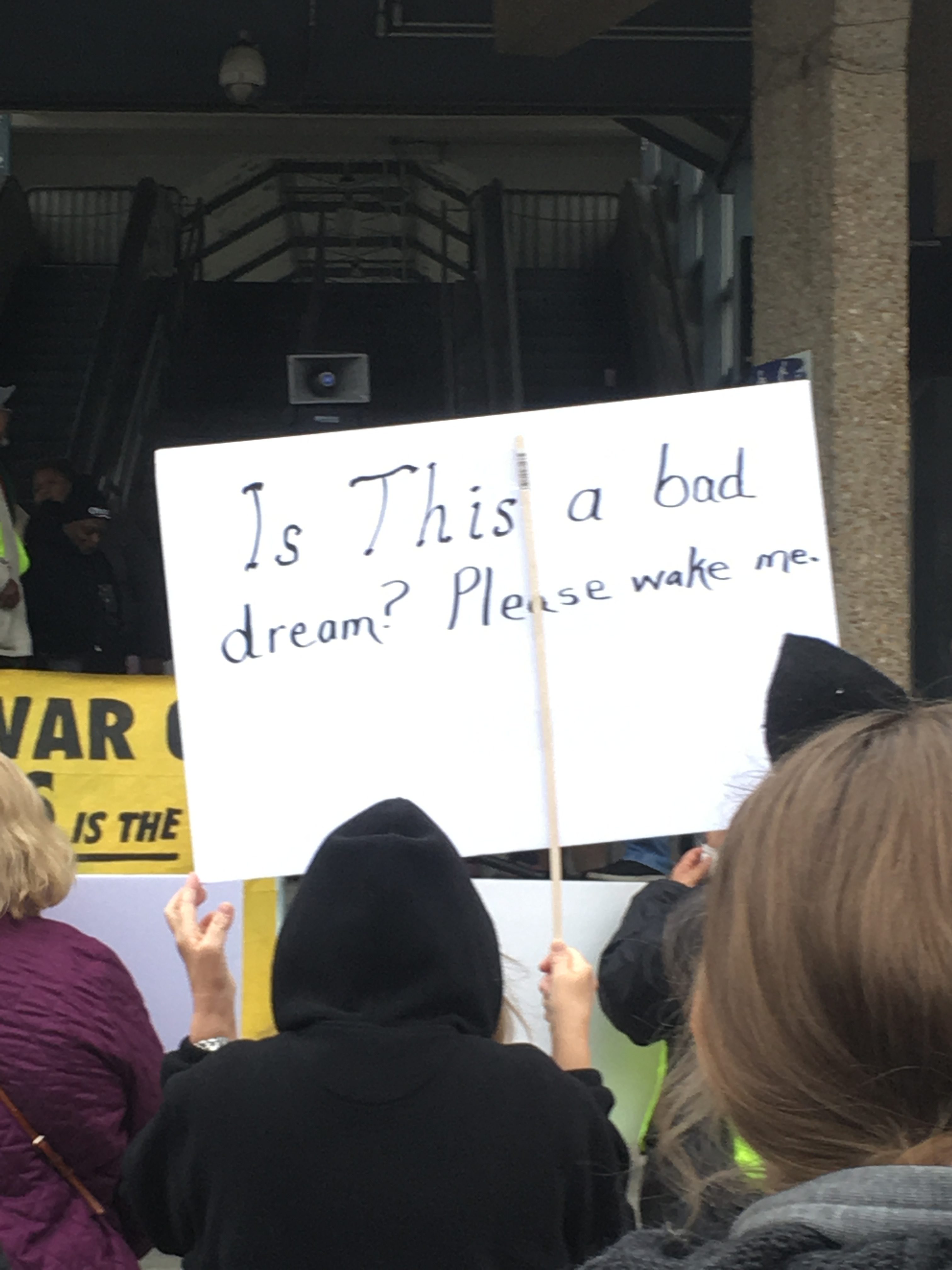

11:01 am: My eye is drawn to a white sign with unadorned black script on a plain white background; stark simplicity in a sea of big block letters and yellow vests. I have to zoom in with my phone camera to read it: “Is This a bad dream? Please wake me.”

Protest signs in New Orleans (Photo: Nora Daniels)

11:02 am: A woman wearing a royal blue hat takes the megaphone. Her perfect dark gold curls bounce slightly as she tells the crowd she’s from the NAACP. “Many of the immigrants are already here. They’ve come here through a student visa; they’ve come here from a worker’s visa,” she says. “They have integrated through all of our cities. Many of the immigrants are already here, they’re citizens. So Trump, step back, MOVE back, and what is your problem? You are the son of an immigrant.”

An older woman with a swirl of grey and aubergine hair passes in front of me, filming with her cell phone. I tell her I love her hair. She thanks me, and then, smiling, asks to borrow my coat. “It’s occupied,” I say. I laugh, because it was supposed to be a situational joke about Occupy Wall Street, and she laughs too, but who knows if it was at that or the slight absurdity of asking to borrow something to serve a basic human need—bodily warmth—at a social justice rally and being turned down by a laughing person. I’d think that was funny too.

11:04 am: The crowd behind me stirs, and everyone’s attention collectively turns toward the street, where a white pickup is backing up to the curb. Attached to the truck is a plywood platform holding a gold structure about 8 feet tall. It is, of course, Donald Trump, clad in a colonial-era costume complete with three-pointed hat, his gut spilling generously over his pants, sitting on a short, chubby nuclear missile as if it’s a small pony, the reigns strapped around its girth leading up to the rider’s left hand. “Fat Boy and Little Man,” I hear a man who’d come out of the pickup call it. He’s the artist—Brent Barnidge—and he says he’s been waiting to unveil “Fat Boy and Little Man” to the world, and today seemed like the perfect time.

Brent Barnidge’s Trump sculpture in New Orleans. (Photo: Nora Daniels)

11:06 am: I check the news to see if there’s any updates about when Trump will arrive and discover the President tweeted how much he loves both farmers and Nashville, Tennessee a few hours ago. Who knows when he’ll arrive in New Orleans, where he’s actually going.

11:20 am: Led by the golden Trump-Napoleon and a man with a megaphone, the march takes off down Canal. “No Trump! No KKK, no fascist USA! No Trump!”

Protesters on Canal Street in New Orleans (Photo: New Orleans)

11:28 am: After a few freezing minutes of getting my bearings, I hustle off to the Convention Center itself to see what’s happening there. Maybe I’d see some Trump supporters. In front of one of the hotels I pass, an older man asks me what the crowd over there is protesting. “Donald Trump is coming,” I say. “Oh, friend. You know,” he says with what sounds to me like sadness, maybe resignation. He could just be tired.

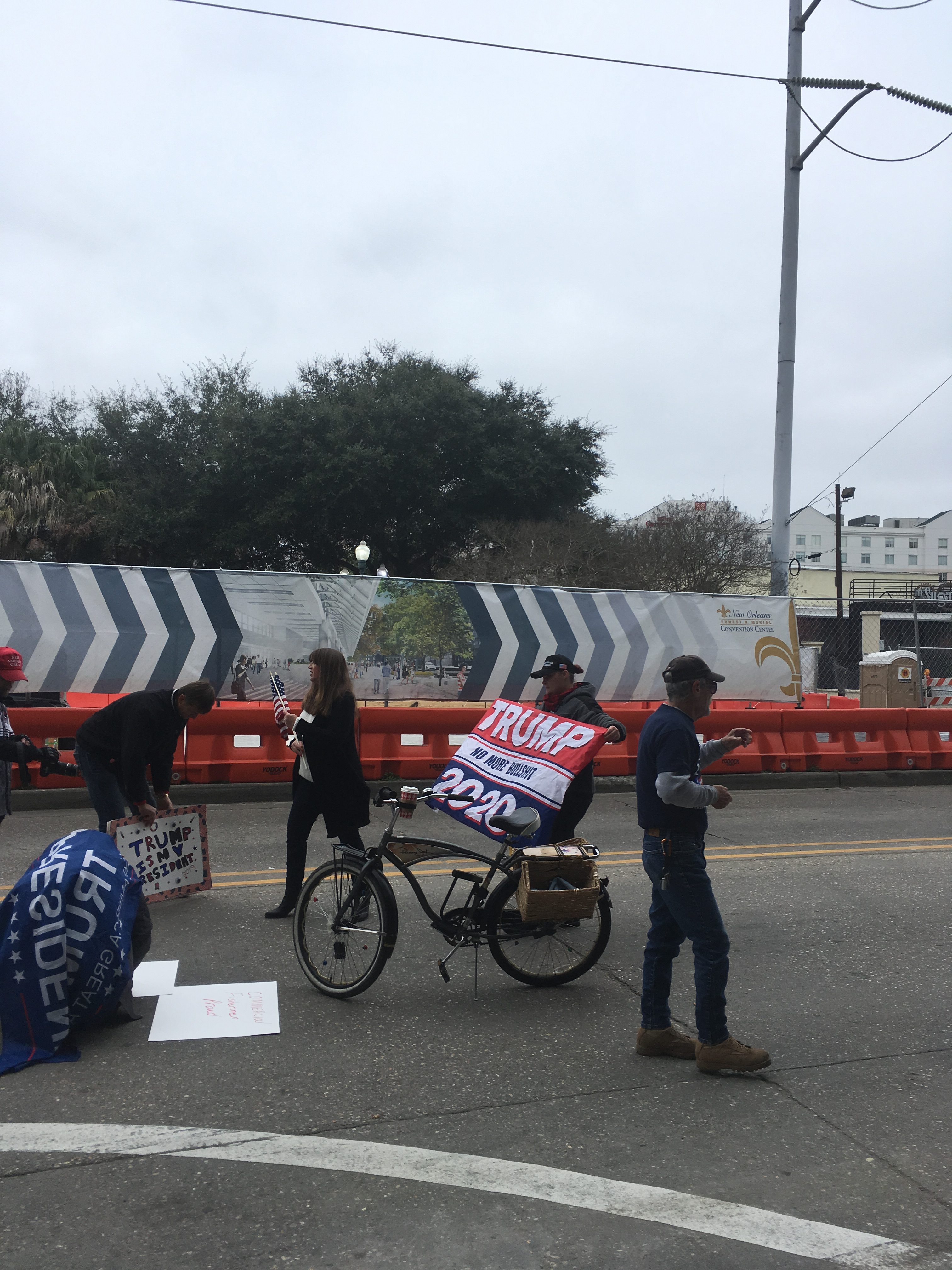

11:37 am: I find a few Trump supporters standing like guards in the middle of Convention Center Boulevard, not far from another protest in front of a police barrier and a cluster of cops. A white man and a white woman wear flags decorated with slogans like, “TRUMP—NO MORE BULLSHIT—2020” on their backs like capes. Another white man wears a light grey football jersey with Trump’s name above the big “45” on the back. They don’t seem to be doing much, just standing and looking at the protest yards away from them.

Trump supporters in New Orleans, January 14, 2019 (Photo: Nora Daniels)

11:41 am: The protest in front of the police barrier appears to be run by the NAACP. A black woman in a matching burgundy scarf and hat who carries the air of an experienced rabble-rouser, leads the crowd, smaller than the one at Convention and Canal but just as loud, in a call-and-response: “Put the workers back to work!” Crowd: “Put the workers back to work!” Woman: “Pay the workers for their work!” Crowd: “Pay the workers for their work!” Woman: “With back-PAY!” The woman in the burgundy hat syncopates this last part about backpay, infusing it with what could only be called funk. I haven’t been to a ton of protests, but something tells me the ability to transform a protest shouts into a groove is a distinctively New Orleans one.

11:43 am: Not as many signs here, but there is a guillotine made out of plywood, topped with a sign that reads: “LET THEM EAT KING CAKE.” After placing a blown-up photo of Trump’s face (altered to make it look as if he’s missing a tooth, making his already exaggerated overbite even more jarring), a man in a army green Dixie Beer-branded beanie poses for photos next to the guillotine, the hand closest to the photo scrunched in a punch.

Protesters in New Orleans (Photo: Nora Daniels)

11:45 am: The woman in the burgundy hat introduces herself as Gaylor Spillers, the president of the West Jefferson Parish Branch of the NAACP. She leads the crowd in another call-and-response. “DONALD TRUMP!” she shouts, as if beckoning a child who has been neglecting their chores and thought no one would notice. The people surrounding her answer. “Hate has no place here!”

11:55 am: I move closer to where more supporters have gathered and try to take some photos before the march comes down Convention Center Boulevard. A couple is joining the group just as I arrive. The woman waves a small American flag like the ones you get on the Fourth of July, while the man, less boisterous than the other men in the group, shuffles through his signs like flashcards. “Over 900 American jobs lost to commercial shrimp Build that wall,” one reads. “Commercial fisherman proud,” “Trump is my president,” read others. With his downcast expression and the signs about commercial fishing, I get the impression that the man isn’t a regular protester, but a blue-collar worker who’s been left behind, his livelihood threatened by globalization and the corporate greed.

As the march gets closer, two large white men pass through the convention center doors. “Build that wall!” one of them shouts to the supporters, grinning. He laughs with his friend as they walk away. As I turn around to look at where they came from, I see a young black man with a bulky professional camera around his neck bum a light for his cigarette from the man in the Trump football jersey. They stand close together, chatting animatedly. From my spot 15 feet away, the only word I can decipher from their conversation is “socialism,” and I’m too rapt by their body language to get closer to hear more.

Protesters in New Orleans (Photo: Nora Daniels)

12:06 pm: Chanting “Trump must go!” the march arrives. More posters have appeared along their route: “GTFO Trump- This is Chewees Country, Cheeto Head!”; “Women’s Rights are Human Rights!”; “TRUMP IS THE CRISIS!” A scruffy gang in bandannas arrive in a cloud of cigarette smoke, holding a banner that reads “[F*#k] All Borders – Refugees Welcome.”

Protesters in New Orleans (Photo: Nora Daniels)

12:18 pm: I make an editorial decision to head back the the streetcar before my face falls off from the cold. I’d planned to see Trump’s arrival, but realized towards the end that of course he wouldn’t actually arrive in front of the Convention Center—he’d probably use some secret entrance that celebrities use.

As I shuffle back towards Canal, I see that the small group of supporters have been pushed off to the side as the tide of marchers flood the street. They stood there a little listless, their signs by their sides, waiting.

12:28 pm: As I’m digging around in my bag for the exact change I know I brought for the streetcar fare, a large white man sitting with a woman near the doors says, “Here, I got you,” and hands me a quarter. “I know it’s in here,” I say, rooting around a little more, then taking the coin from his outstretched hand. I told him I’d find mine and give it back to him when I sat down. He shook his head, smiling. Not necessary. Eventually I found the quarter in a different pocket than I’d been looking in and gave it to the man. “Thank you,” he says.

Protesters in New Orleans (Photo: Nora Daniels)

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.