EDITOR’S NOTE: New Orleans is a city that is considered to be one of the top tourist destinations in the United States, receiving almost 20 million tourists a year. One of those reasons is the unique architectural styles found throughout the city, such as French influence and shotgun homes. Another is the unique style of city planning that began in Jackson square and follows the form of the Mississippi River. The history of the unique architectural styles is something New Orleans natives and those who visit should be informed on — everything from street tiles to not-so-tall buildings. This piece on stopping gentrification was originally published on March 30th 2022.

It’s March, so we are marching into solutions. Yes, we’re aware of how lame that pun is! We also think it’s lame that a lot of journalism likes to describe everything that’s wrong with the world without showing data-driven examples of solutions that work! We don’t accept that, so this month we are marching (oof, there it is again) into solutions. We’ll be taking issues/problems from the Nola community and doing the research to find solutions that have proven to work! It’s solution journalism, and we’re continuing with a look of supposed “development.”

Ariel view of I-10 near the Claiborne Corridor. (Photo by: Wikimedia).

Part I: The Issue

The United States before the construction of the Interstate Highway System is a landscape unrecognizable to the modern American citizen. For years, the automobile industry and related manufacturing industries pushed for the creation of usable, well-connected roads, but it was not until President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act in 1956 that the long-awaited dream of a continental highway system had the funding to be fully actualized.

The Interstate Highway system created a 41,000-mile system of “Interstate and Defense” highways intended to eliminate traffic congestion, ease transcontinental travel, and make swift potential evacuations from cities possible. However, highway advocates also believed that highway construction would replace “undesirable slum areas” with more visually appealing concrete structures.

While the highway system accomplished its primary, more noble goals, it also accomplished the latter. One of the “undesirable slum areas” destroyed as a result of the highway system was Tremé – a historic New Orleans neighborhood and the oldest African-American neighborhood in the United States.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Tremé was a vibrant community, where “history feels like it’s present.” At its heart lay Claiborne Avenue, a wide street lined with oak trees that was walkable and full of family homes and locally black-owned businesses. Longtime residents describe the street as a place whose community felt like family. On Claiborne Ave., the sound of people talking and selling food and other goods over the sound of New Orleans jazz created a sense of festivity. In the height of Jim Crow, Black Americans had built a place where everything they needed existed within their neighborhood – where “life for Black Americans was fully realized.”

But this neighborhood began to vanish as soon as the oak trees came down in Feb. 1966. People saw construction at every turn, and as the now-familiar Claiborne Expressway was built, homes and businesses of Tremé residents disappeared.

By 1968, Claiborne Ave. was no longer walkable. Shoppers who used to frequent Claiborne were forced to go to Canal Street, where Jim Crow America and white-owned shops denied fair treatment to Black Americans. Black individuals had to change the way they carried themselves to avoid accusations of thievery. The expressway rerouted traffic and made Claiborne Ave. less accessible for residents. Consequently, businesses started to fail as local clientele decreased. With over 500 homes demolished and dozens of businesses closed, the economic backbone of the neighborhood’s vibrancy was gutted.

The community of Tremé changed, too, as it learned to exist in the shadow of the highway. The overpass – a dark structure which some call “the Monster” became a cover for prostitution, drugs, homelessness and crime. Just a few dozen businesses exist in the neighborhood in the 2020s, and residents are constantly bombarded with the sights, sounds and smells of highway congestion. These factors worsen with every major city event that requires use of the expressway.

To make matters worse, the expressway causes health detriments to Tremé residents, who suffer rates of asthma higher than the average – from pollution –and live near lead-contaminated soil – from leaded gas. A surplus of asphalt, concrete and other heat-absorbing surfaces contribute to New Orleans’ status as America’s worst heat island, describing an urban area that experiences higher temperatures than outlying areas. Structures like the Claiborne Expressway only worsen the climate impact of heat islands as hot vehicles raise the temperature of the surrounding areas and parking lots meant to accommodate more cars replace green spaces. Claiborne Ave. and Tremé in a post-expressway world are, like other cities wrecked by highway infrastructure, vastly different than they once were.

These cities include Rochester, New York, altered by the Inner Loop; Detroit, Michigan, by I-375 and I-75 and New Haven, Connecticut, by Route 34 among many more. Nadja Popovich of the New York Times describes that, due to highway development,“White Americans increasingly fled cities altogether, following newly built roads to the growing suburbs. But Black residents were largely barred from doing the same. Government policies denied them access to federally backed mortgages and private discrimination narrowed the options further. In effect, that left many Black residents living along the highways’ paths.”

As mid-century infrastructure deteriorates and modern-day politicians address the issues they’ve caused and are still causing – specifically to communities of color – questions are being raised about how to repair divided neighborhoods. This question becomes all the more applicable with the passing of the $1 trillion Biden Administration infrastructure bill which aims to provide money to state and local governments to “upgrade outdated roads, bridges, transit systems and more.” Just $1 billion out of the total funding is allocated to repairing neighborhoods divided by highways, compared to the $20 billion that the administration originally proposed and the $500 million that studies estimate the removal of the Claiborne Expressway will cost. In the project, the Biden Administration has stated that racial equity should be a lens through which infrastructure projects should be assessed, pointing specifically to New Orleans as an example of how infrastructure divided communities and exacerbated racial inequalities. Now the question remains: what should be the future of the Claiborne Expressway and its surrounding neighborhood?

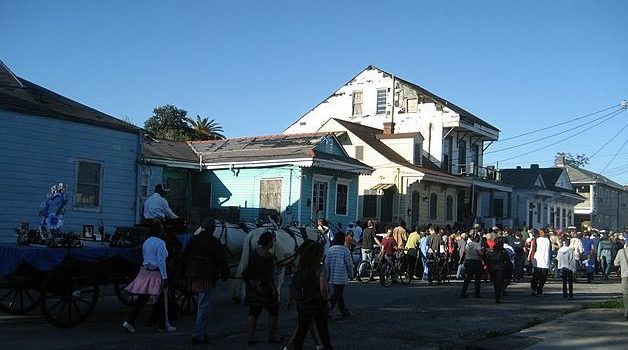

All Saints Second Line in Treme 2009

source: Infrogmation

PART II: The Solution

Areas served by highway construction consider two primary solutions to reconnect neighborhoods: removal and renovation. San Francisco’s Embarcadero Freeway was rendered unusable after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. In 2002, a section of it was removed and replaced with a multi-use boulevard. The freeway had previously cut the city off from its waterfront and shoved long ramps into neighborhood areas. The plan to connect the city back to the waterfront sought the following goals: a working waterfront, a revitalized port, a diversity of activities and people, access to and along the waterfront, an evolving waterfront – mindful of its past and present, urban design worthy of the waterfront setting, and economic access that reflects the diversity of San Francisco.

The tremendous effort to remove a decrepit highway and replace it with aesthetically pleasing infrastructure that is conducive to the surrounding community is a lengthy and complicated one. Proposals to remove the freeway went before the city’s voters and were rejected three times before the San Francisco Mayor, Art Agnos, pushed the removal plan through in 1991. The final plan, the Waterfront Land Use Plan, was a product of a public and multi-stake holder planning process. It featured clearly outlined goals, policy and guidance for public and private investmentment and suggestions for design that took into account the character of the area and the diverse demographic that would use it. The boulevard cost less than $50 million to build, which was less than the $69.5 million estimated to reconstruct the freeway. Further, the extensive planning of the boulevard contributed to significant success years later.

Now, a multi-use boulevard with a 25-foot-wide, palm tree-lined pedestrian walkway exists in place of the Embarcadero Highway. The boulevard anchors together South Beach, with housing, retail and the San Francisco Giants field; Rincon Hill, a neighborhood with a public art space; the Gap Headquarters, a retail area; the Ferry Building, a commuter ferry port that houses a farmer’s market and shops; and Historic Piers 1, 1 ½, 3 and 5, which are office and retail spaces. Now, this area is a “thriving local and tourist destination” where housing has increased by 51% and jobs have increased by 23%.

Other projects repurpose existing infrastructure to convert highways into multi-use spaces similar to the Embarcadero Boulevard. Toronto’s Bentway, which revitalized Toronto’s Gardiner Expressway, utilized the existing architecture of an overpass to create a series of community spaces that are divided by the columns of the underpass. According to WaterfronToronto, the project “is focused on helping Torontonians reclaim and transform this underused space for active community use, making it possible to host diverse events.”

As of 2018, the underpass shades a green space accompanied by a bike-friendly sidewalk. A large staircase acts as seating for a theatre, and there are programming and performance spaces for community use. The area is home to farmer’s markets, chamber concerts, dance competitions, experimental theatre, street art festivals and kids’ camps.

The Bentway project relied on public input that respected the structure of the Gardiner expressway while incorporating the opinions of community groups, sport, recreation, arts, culture and entertainment organizations, and the greater public. The question, “What could only happen here?” guided the vision of the space. Further, construction was supported by a $25 million dollar donation from philanthropists Judy and Wil Matthews to the city of Toronto. The Bentway is a perfect example of imprinting a new vision onto outdated infrastructure that cultivates a diverse and vibrant community.

Solutions to highway construction must also suit the needs of existing communities. This goal was accomplished in Rochester, New York, where infrastructure replaced the city’s Inner Loop, an old beltway with 12 vehicle lanes, ramps and roads. The renamed Union Street has two to four vehicle lanes, parking lanes, sidewalks, two-way protected bike lanes, signaled crosswalks, bike racks, benches, trees and landscaping. Between 2014 and 2019 (the boulevard was completed in 2017), walking increased 50%, biking increased 60% and the city expects more pedestrian and bike traffic as development around the area increases.

Aside from the physical infrastructure that replaced the Inner Loop, the project in Rochester also focused on housing and community building to revitalize a neighborhood that fell into racial and socioeconomic downfall. In progress, the new neighborhood around the former expressway will include 534 housing units, more than half of which will be subsidized or offered below market rate. Some of these housing projects are reserved for ex-offenders re-entering the workforce, people living with HIV and seniors requiring assistance. It will also offer 152,000 square feet of commercial space, including a day-care center, restaurants and a pharmacy, which the downtown area lacked. By assessing community needs, the repurposing of infrastructure can begin to rebuild the community and offer it resources it has previously been denied.

To be beneficial to communities, removal and repurposing projects must incorporate public opinion and debate, which further stall construction. Often, communities affected by highway infrastructure do not have sufficient funds to complete these mass-construction projects that can cost millions and even billions of dollars, so they rely on donors or government money.

Some neighborhood residents fear that gentrification will accelerate if highways are removed and repurposed. Others believe that green spaces created on top of abandoned infrastructure can keep out gentrifiers; regardless it is imperative that no further harm is done to members of affected communities. San Francisco’s Central Freeway, which was once proposed to connect with the Embarcadero Freeway, was altered after the Loma Prieta Earthquake. While the project that replaced it is visually appealing, pedestrian friendly and full of landscaping, side lines, parking, and pedestrian amenities, economic development in the area has contributed to increasing gentrification.

When discussing what should be done with New Orleans’ Claiborne Expressway, project planners must consider successes of similar projects, community needs and limitations of construction projects all the same.

Kermit’s Treme Mother in Law Lounge 1500 North Claiborne (Photo by: Kelley Crawford)

PART III: Implementing the Solution in New Orleans

As it concerns the Monster, strangely enough, the Tremé community has adapted to the structure. According to longtime resident Lynette Boutte, Claiborne Ave. is still “meeting place central.” In the absence of the original street, people still gather under the bridge and entrepreneurs sell anything from jewelry to food and even bring portable daiquiri machines. Bands still play music. The neighborhood is not the same, “but it has heart.” Heart is something difficult to eradicate in New Orleans.

Many residents, like Leanne, believe that the only solution is to embrace the highway to preserve the resilient community that resides around it. These individuals believe that removing the highway would be useless; the oak trees cannot be regrown and removing the highway may usher in a wave of gentrification.

Like the Bentway in Toronto, the Claiborne Expressway must be transformed into a multi-use greenspace with sidewalks, bike paths and seating areas for music and entertainment. An environment like this would fit in perfectly in New Orleans, known for music, entertainment and gathering. Further, Claiborne Ave. and Tremé used to be ground zero for Black Mardi Gras and Second Lines, which require walkable paths. If the Claiborne Expressway underpass were to be converted into an area like the Beltway, the column under the Expressway could divide areas into community spaces, meeting places, theatres and parks. The highway stripped Claiborne Ave. and Tremé of houses, businesses, community space, accessible sidewalks and natural beauty. It must be understood that these aspects of a neighborhood are vital to its health and a repurposed infrastructure must attempt to bring them back.

Any adjustment of current infrastructure would be costly. A study suggests that $500 million would be necessary to remove the highway, but the Rochester Inner Loop project required $22 million in planning and construction, $17.7 million in federal grant funds, $3.8 million in state matching funds and $414,000 in city matching funds. This project began almost a decade ago, so costs would be higher for a similar project for the expressway. Still, repurposing would likely be more cost effective than removal and, if done correctly, can generate significant income for the city.

The average household income in Tremé is $26,200, far below the national average in 2019 – $68,703. This statistic suggests that new housing in the area should be reasonably priced for those already living in Tremé. Like the Rochester Inner Loop construction project, a portion of new housing built should be subsidized or offered below market price. Approximately 67% of housing units in Tremé are occupied, but it may be the case that the potential of new housing could attract more residents.

Longtime residents of Tremé note that walkability was essential to the neighborhood’s deep sense of community. When the Claiborne Expressway is updated, it must incorporate sidewalks and signaled crosswalks that allow people to travel through the area safely so that they are protected from traffic. Although most Claiborne residents primarily travel by car, adding protected bike lanes and a bus stop could discourage excessive car use and encourage other modes of travel. Statistics from the Rochester project suggest that walking and biking will increase when infrastructure is developed that makes these activities possible.

Any plan to update the Claiborne Expressway also must focus on economic development. Tremé used to be filled with local businesses, bars and clubs. Community culture could be a huge selling point to attract businesses into the area. Resources show that “cultivating a collaborative, creative, appealing, and genuinely thriving community fuels hope and optimism” and attracts businesses into the area. Further, start-ups and already existing businesses should have help in accessing capital.

The idea of renovating highways like the Claiborne Expressway is not a new one. The blueprints to successfully reconnect a divided community already exist and Tremé residents have already taken efforts to formulate a plan as to how to fix the area. If the Biden Administration allocates proper funds to this unique New Orleans neighborhood, it will finally have the chance to make this community whole – albeit in a new way that should not erase the history of Tremé and the destruction the highway caused.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.