Hi, I’m Dr. Molly Marty with Resiliency Matters and today we are speaking with Dylan Tett, a graduate of west point and founding executive director of Bastion Community of Resilience. I’m thrilled to say Dylan is also World Makers 2021 Trailblazer Honoree. So much to talk about, Welcome Dylan!

— Thank you; good to be with you Molly.

Can we start by you sharing some of the things that you experienced or observed after returning from serving in Iraq?

— My life is a bit unique in that regard I redeployed in ’04 and moved to New Orleans three months before Hurricane Katrina. In some respects, I was at the right place at the right time, but I really never had a shot at a normal life. You know the the things that I was grappling with at the time were things like hyper-vigilance and depression and suicide ideation. I felt completely alone and disconnected. I felt completely out of place. I felt my best when I was working, since we work ourselves as a coping mechanism to cover up or hide a lot of the pain and loss that we’re experiencing. That’s just a little taste of what I was going through at the time.

My life after Hurricane Katrina completely changed again, and a lot of the things that the army trained me to do actually melded very well in the greatest rebuilding effort since the Marshall plan. At my worst, I did want to end my life, but, luckily I did get the help I needed and started volunteering at a summer adventure camp for gold star kids. Those kids taught me a new expression of courage, which is the courage to live on, and that was really the beginning of about a 10-year journey to come all the way home.

We are so very very very grateful you are here with us. You know you hold a very special place in my heart. I mean you and your comment about you know you had no shot at a normal life, I would say is there such a thing or if there is I think it’s overrated.

— Amen

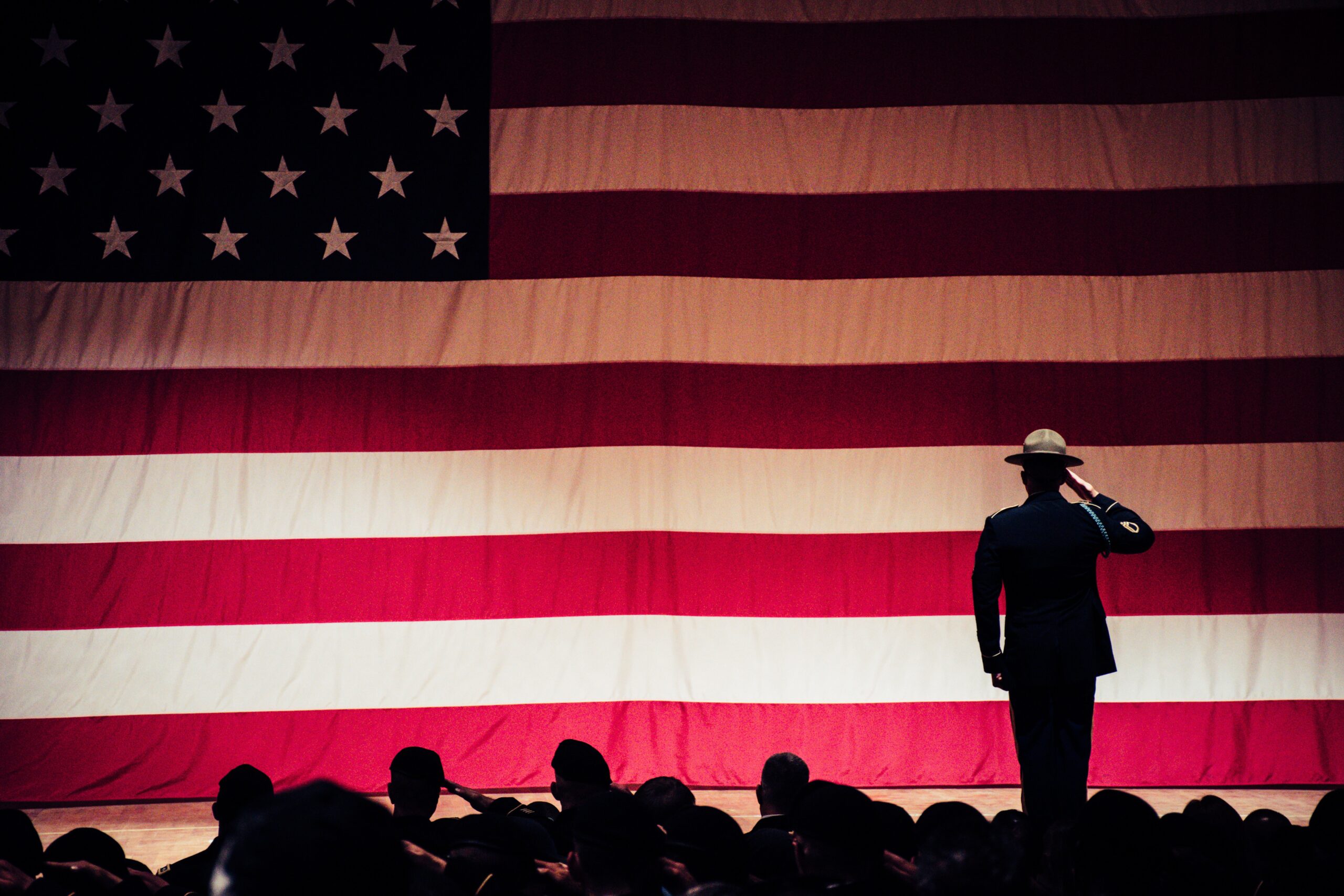

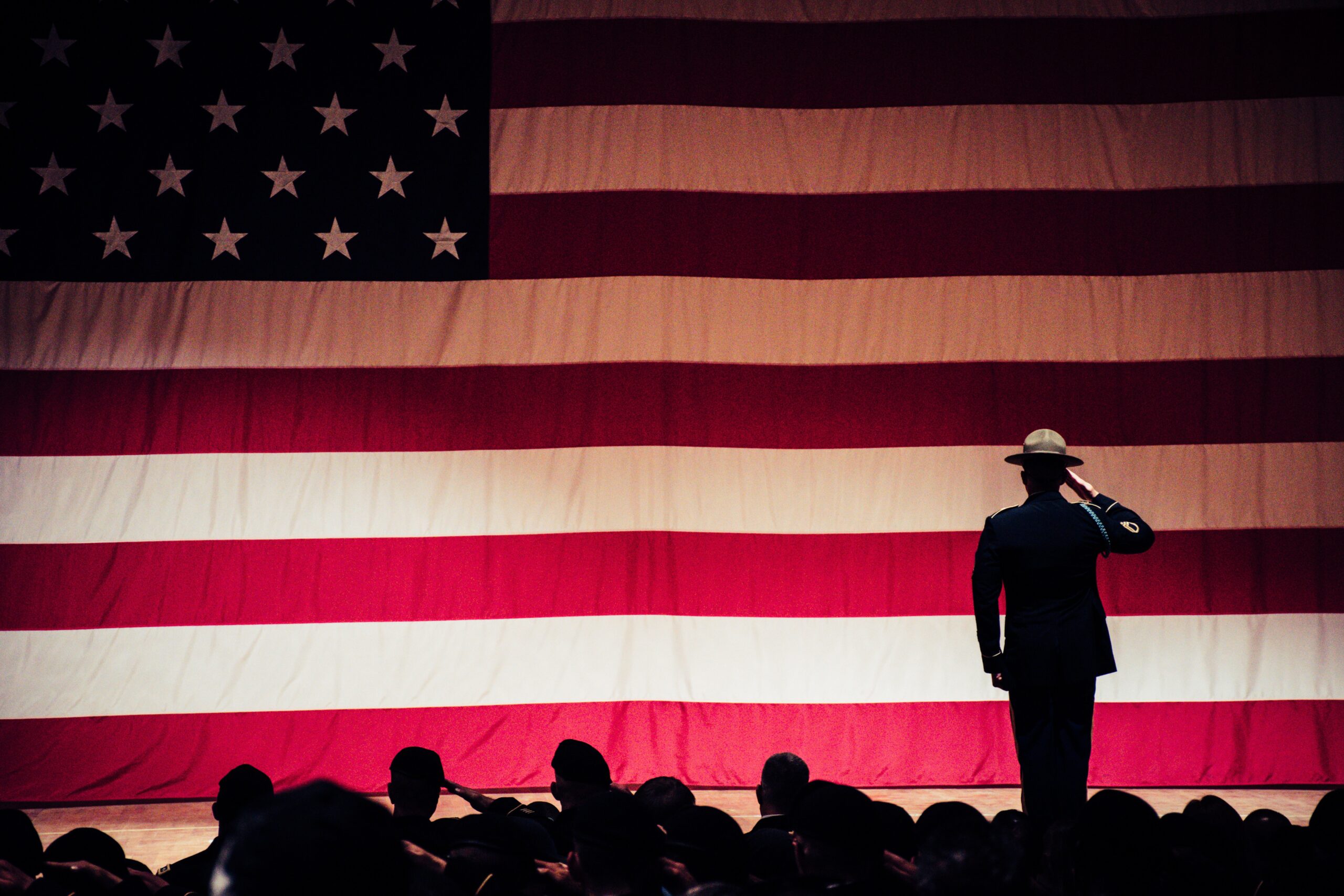

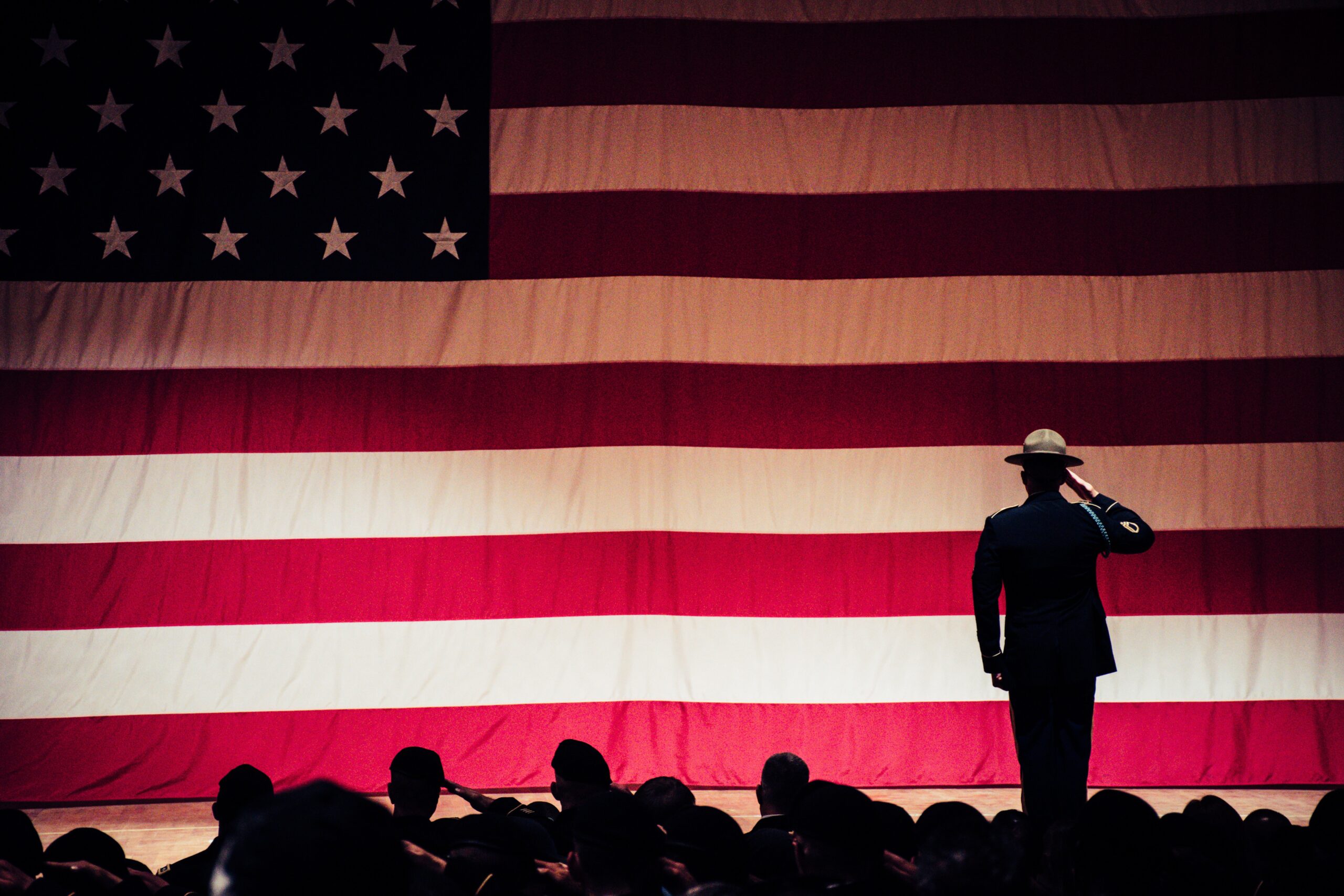

Deployment and military-related movement can result in concern, panic, and loneliness for family members. (Image created by Brett Sayles)

You started looking for solutions and you came across the work of Dr Brenda Hart, a friend in common (I encourage our viewers to watch Brenda’s show). She wrote a brilliant book called Neighbors, it’s at worldmakerinternational.org. What really resonated with you about Brenda’s model of intentional neighboring?

— Fast forward a few years, and my buddies were coming home with this thing called traumatic brain injury (TBI). I had no idea what it was, and I got very curious about it. I went to the pentagon. I went to Walter Reed and the Center for the Intrepid in San Antonio. I went to the hub of the VA’s Polytrauma Network and what everyone described to me — the doctors, the warriors themselves, their caregivers, and loved ones — was that there wasn’t just a gap in the continuum of care, there was a cliff.

Once these warriors were discharged from the hospital, the communities they were moving back to were not equipped to sustain them, to make them viable, to keep them moving forward. I went to a group home that the VA was funding; I thought maybe this could be a solution. It actually made me angry when I walked inside. It’s not a place I wanted to live. I met a young warrior in his 20s who was so over medicated that he was drooling out the side of his mouth on a couch with no one around him. I thought we could do better than this.

I stumbled on this blueprint that Brenda pioneered for foster youth and adoptive families, and we began to adapt it for military demographic. I have to say it has worked very very well. It took me a little while to convince enough people that this idea could work, but we purchased five acres started building homes. Today there are 58 households who call bastion home. We have a clubhouse, and we’re doing lots of wonderful programming and we are now on the threshold to build 14,000 square foot commercial wellness center that will open to the public and share with them what we’re learning about trauma and resilience. Community is central; it is pivotal; it is the linchpin and the ongoing recovery and reintegration for warriors. I would say anyone who who has experienced trauma needs a community to keep them grounded and to keep them moving forward.

So talk a little bit about the service component. You have this intentional neighboring — really a mandatory service — as part of that community. Help our viewers understand more of the context.

— Service has evolved. That idea of it has evolved since we started. There is a an ethos; it is it is partly the warriors ethos of not leaving anyone behind. So beginning with this sort of expectation of service, we began to uncover a lot of the complexity of our warriors and their families. Some of it was not military connected; it was linked to poverty, adverse childhood experiences, such as growing up Black in the south. The idea of service began to evolve.

Our professional staff, which is composed of occupational therapists, social workers, and certified brain injury specialists, has many functions, and one of their primary functions is integrating neighbors into the care plan. It’s a process of customizing each household’s approach to their own health and healing, but it’s done in partnership with their next-door neighbors. We have retired elders, who, in fact, have even sold their homes to live at bastion and give that kind of instrumental support and peer support that some of our warriors need. If you think about TBI, in the most severe cases these are folks who need skilled care; these are folks who need help with their activities of daily living that you and I take for granted.

It really does take a village, not to be cliche, but when you have that kind of support built in next door it makes all the difference. We’re not tracking everyone’s service hours anymore because the expectation of service was so well ingrained in the beginning and through the orientation and indoctrination of residents as they flowed in. We are all growing together, and it’s amazing to watch how even when our elders need support, our warriors are there to help them. Let’s not forget, we have between 30 and 40 children who live at bastion as well — playing pivotal roles in the recovery reintegration of our warriors and in the quality of life of our elders. Everyone’s benefiting; it’s just beautiful.

It’s it is beautiful and brilliant. It’s true culture change is what you’re describing.

–Yes, yes

You gifted me this way back when when we first met, but it’s your user guide to Bastion, and I want to read a bit from it as we move into the mind/body discussion. It says “military instruction is reinforced with the type of physicality that can sometimes border the psychotic. We are trained to ignore our bodies for survival; we embody [this] long into our post-military lives. It’s no wonder that so many veterans find it difficult to speak about painful emotions. We have effectively disconnected ourselves from the true pain we feel in our bodies due to trauma, loss, broken relationships, or moral injury, and the same is true for feeling joy, peace, or love. Let us also remember that veterans do not own the monopoly on pain and epic struggle. Everyone experiences trauma at some point in life. “There’s a lot to unpack there; where do you want to take this?

— Well, on my journey to wholeness, I again stumbled on a model for healing in community. This is a model that the center for mind-body medicine has used all over the world for the last 30 years. We’re using it at Bastion. I’ve taken it to Ukraine to heal veterans from the war, but what I have seen in every location I’ve gone to where I’ve used this model is very personal transformations occurring in real time. I mean, you can see it happening before your very eyes.

I’ve experienced this type of healing coming back from Iraq. I think there was some type of spiritual death. It has taken the better of 10 years to effectively turn this body back on that I had effectively turned off. It took time to connect my mind with my body and with my spirit once again. Recruiting the whole body to heal is something that, as I said before, it’s transformative. So when you do it in a community, the effects and the benefits of that transformation tend to persist a lot longer than they would in a one-on-one type of professional client relationship.

I think you’ll appreciate this, Dylan, I was listening to an Arabic scholar over the weekend, and he was pointing out in various languages they don’t have when you talk about as the mind-body connection. They don’t have a word for body; their only word for body is “corpse,” like the body is simply a container. Then we, in western civilization, can track it back to certain philosophers and and philosophies. We’ve created this distinction. We act like we need to put this mind and body and spirit and emotions back together when it was whole all along, and we’ve created these constructs that create separations. Have you ever heard that?

— No, that’s fascinating.

It was really profound. I’ll share the source with you. All right viewers more on post-traumatic growth and resilience stay tuned… welcome back to Resiliency Matters today we’re speaking with Dylan Tett. Dylan, I was thinking, as I was thinking about you and prepping the show, that I have filmed over 50 episodes, and I’ve never talked to a guest about Joseph Camel’s The Hero’s Journey. Although, I know many of them are well-versed in it. So I’ve been saving this for you because I know that this is part of your structure. Share with viewers a bit about “The Hero’s Journey”.

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...  Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.

Voodoo in New Orleans: Reviving history: New Orleans fortune telling This article takes a deep dive into the history of Voodoo in New Orleans, its hybridization with Catholicism, and its present-day place in the city's culture. The author visits fortune-tellers in the French Quarter, using their guidance as a tool for introspection rather than a deterministic predictor of the future. Through her experiences in New Orleans, the author feels a mystical connection to both the past and the future.